Race

Ways that Race Can Affect Death Sentencing

Studies from across the nation have examined the influence of race in the application of the criminal justice system. Many have shown that race remains a factor in various aspects of death penalty.

Race of the Victim

Nationally, around 75% of murder victims in cases resulting in an execution have been white, even though nationally only 40% of murder victims generally are white. A 1990 examination of death penalty sentencing conducted by the United States General Accounting Office noted that, “In 82% of the studies [reviewed], race of the victim was found to influence the likelihood of being charged with capital murder or receiving the death penalty, i.e., those who murdered whites were found more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered blacks.” Individual state studies have found similar disparities. In fact, race of victim disparities have been found in most death penalty states. For example:

- “Race and the Death Penalty in North Carolina An Empirical Analysis: 1993 – 1997″ This study, the most comprehensive ever conducted on the death penalty in North Carolina, was released by researchers from the University of North Carolina. The study, based on data collected from court records of 502 murder cases from 1993 to 1997, found that race plays a significant role in who gets the death penalty. Prof. Jack Boger and Dr. Isaac Unah of the University of North Carolina found that defendants whose victims are white are 3.5 times more likely to be sentenced to death than those with non-white victims. “The odds are supposed to be zero that race plays a role,” said Dr. Unah. “No matter how the data was analyzed, the race of the victim always emerged as an important factor in who received the death penalty.”

- According to the findings of a Governor-commissioned death penalty study conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland, the state’s death penalty system is tainted with racial bias, and geography plays a significant role in who faces a capital conviction. The study, one of the nation’s most comprehensive official reviews on race and the death penalty, concluded that defendants are much more likely to be sentenced to death if they have killed a white person. See DPIC’s Press Release. For more information about the study, see the Complete Study (Released on January 7, 2003).

- “Impact of Legally Inappropriate Factors on Death Sentencing for California Homicides, 1990 – 1999, The Empirical Analysis” by Glenn Pierce and Michael Radelet. According to this 2005 study, defendants in California who were convicted of killing non-Hispanic white victims were sentenced to death at a rate of 1.75 per 100 victims, compared to a rate of just 0.47 for non-Hispanic Black victims. In turn, homicides involving non-Hispanic white victims are 3.7 times more likely to result in a death sentence than those including non-Hispanic Black victims. Defendants convicted of killing Hispanic victims were sentenced at 0.369 times the rate as those convicted of killing white individuals, indicating white victim homicides are 4.73 times more likely to result in death sentences as Hispanic victims. Controlling for all predictor variables, defendants convicted of killing non-Hispanic Black people are 59% less likely to be sentenced to death than defendants who kill non-Hispanic white victims. This difference increases to 67% when comparing sentencing rates of defendants who killed white victims with defendants who killed Hispanic victims.

- “Death Sentencing in East Baton Rouge Parish, 1990 – 2008″ by Glenn Pierce and Michael Radelet. This 2011 study concluded that 12 out of 56 (21.4%) defendants who killed white people between 1990 and 2008 were sentenced to death, while just 11 of 135 (8.1%) defendants who killed Black people were sentenced to death. This means that individuals who killed white victims were 2.6 times more likely to be sentenced to death than those who killed Black victims. 30% of Black defendants convicted of killing white victims were sentenced to death while just 12.1% of white people convicted of killing white people were sentenced to death. 8.3% of Black people convicted of killing Black victims were sentenced to death, while no white defendants were sentenced to death for killing Black victims.

- “Race and Death Sentencing for Oklahoma Homicides Committed Between 1990 – 2012” This study investigated how race plays a role in the distribution of death sentences and found a strong correlation between the race of the victim and death sentencing, rather than the race of the defendant. According to this study, an individual is more likely to receive a death sentence for killing a white victim than for killing a non-white victim. (Released in 2017)

- “A Systematic Lottery: The Texas Death Penalty, 1976 to 2016″ by Scott Phillips and Trent Steidley. According to a 2020 study focused on the administration of capital punishment in Texas from 1976 through 2016, white females are valued more highly than the lives of other victims. Among death-eligible defendants in Texas, 12.9% killed a white female. However, among those who were sentenced to death, 35.8% killed a white victim. This means that a defendant who killed a white female was 2.8 times more likely to be sentenced to death than a defendant who did not kill a white female.

- “The Race of Defendants and Victims in Pennsylvania Death Penalty Decisions: 2000 – 2010″ by Jeffrey Ulmer et al. According to a 2022 study focused on capital cases in Pennsylvania from 2000 to 2010, cases with white victims, regardless of the defendant’s race, were 8% more likely to receive death sentences, and 7% more likely to receive one when controlling for county differences.

Race of the Defendant

Nationally, the racial composition of those on death row is 42% white, 41% Black, and 14% Latinx. Of states with more than 10 people on death row, Texas (74%) and Louisiana (73%) have the largest percentage of minorities on death row. 2020 census data revealed that the racial composition of the United States was 58.9% white (not Hispanic or Latino), 13.6% Black and 19.1% Hispanic or Latino. While these statistics might suggest that minorities are overrepresented on death row, the same statistical studies that have found evidence of race of victim effects in capital sentencing have not always found evidence of similar race of defendant effects. However, race of the defendant effects have been found in some jurisdictions. For example:

- In the 2024 article “Implicit Bias and Jury Trials: A Report on an Experiment in Washington,” author Dave McGowan examines the influence of implicit racial bias within the jury trial process in Washington state. This report highlights several significant cases including State v. Berhe, where the Washington Supreme Court ordered an evidentiary hearing to investigate potential racial bias influencing the jury’s decision. This decision reflects the court’s recognition of the difficulty in identifying implicit bias, as jurors might not be aware of their own biases or may not admit to them.

- “Looking Deathworthy: Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants Predicts Capital-Sentencing Outcomes” by Jennifer Eberhardt et al. Using more than 600 death-eligible cases from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in which a Black defendant was charged with killing a white victim, researchers found that 24.4% of defendants who appeared less stereotypically Black received a death sentence, while 57.5% of those who appeared more stereotypically Black received a death sentences. Students at Stanford University rated the degree of stereotypical features from photos of Black male defendants who had been convicted of murder in Philadelphia.

- According to a recently updated study by Professor Katherine Beckett of the University of Washington, jurors in Washington “were four and one half times more likely to impose a sentence of death when the defendant was black than [] they were in cases involving similarly situated white defendants.” The earlier version of the study had found that juries were three times more likely to recommend a death sentence for a black defendant than for a white defendant in a similar case. The disparity in sentencing occurred despite the fact that prosecutors were slightly more likely to seek the death penalty against white defendants. The study examined 285 cases in which defendants were convicted of aggravated murder. The cases were analyzed for factors that might influence sentencing, including the number of victims, the prior criminal record of the defendant, and the number of aggravating factors alleged by the prosecutor. THE ROLE OF RACE IN WASHINGTON STATE CAPITAL SENTENCING, 1981 – 2014 (Originally published Jan. 27, 2014, updated with additional data 2015). The original version of the study, covering only 1981 – 2012, is available here.

Race of the Jurors

In capital cases, one juror can represent the difference between life and death. A belief that members of one race, gender, or religion might generally be less inclined to impose a death sentence can lead the prosecutor to allow as few of such jurors as possible. For example:

- A Dallas Morning News review of trials in that jurisdiction found systematic exclusion of Black individuals from juries. In a two-year study of over 100 felony cases in Dallas County, the prosecutors dismissed Black people from jury service twice as often as white people. Even when the newspaper compared similar jurors who had expressed opinions about the criminal justice system (a reason that prosecutors had given for the elimination of jurors, claiming that race was not a factor), black jurors were excused at a much higher rate than white jurors. Of jurors who said that either they or someone close to them had had a bad experience with the police or the courts, prosecutors struck 100% of the Black potential jurors, but only 39% of the white potential jurors.

- “Forecasting Life and Death: Juror Race, Religion, and Attitude Toward the Death Penalty” by Theodore Eisenberg et al. This study concluded that among its data set, a white juror was 20% more likely to cast their first vote for death than a black juror. “All else being equal, white jurors are more apt to vote for death than are black jurors,” and because the majority tends to rule the final verdict in capital cases, Black people are rarely in the majority of South Carolina capital juries.

Race of the Prosecutor

Whenever and wherever capital punishment is authorized by law, the decision whether or not to seek a death sentence in particular cases is left to the discretion of the prosecutor. Surveys of prosecutors have found a striking lack of diversity. For example:

- A 1998 examination of Chief District Attorneys in states with the death penalty found that nearly 98% are white, 1% are black, and 1% are Hispanic.

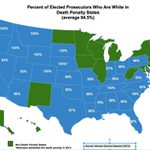

- According to a study by the Women Donors Network, 95% of elected prosecutors in the U.S. are white and 79% are white men. An analysis by DPIC of the study’s data further shows that, in states that have the death penalty, 94.5% of elected prosecutors are white. In 9 death penalty

states (Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington, and Wyoming), 100% of elected prosecutors are white. (N. Fandos, “A Study Documents the Paucity of Black Elected Prosecutors: Zero in Most States,” The New York Times, July 7, 2015). “Equal justice under law? Prosecutor demographics and the death penalty” by Jami-Reese Darling Robertson and Lauren C. Bell. According to a 2022 study published in the Social Science Quarterly, the race of a prosecutor has a statistically significant impact on sentencing outcomes in death-eligible cases. Of the 54 prosecutions led by non-white prosecutors, just five (9.3%) resulted in a death sentence, four of which were prosecuted by non-white women. Only one case (1.5%) of the 67 cases that ended in a death sentence and for which demographic data was fully available was prosecuted by a non-white, male prosecutor.