The Death Penalty in 2019: Year End Report

New Hampshire Abolishes Death Penalty, California Imposes Moratorium

Half of U.S. Has Abolished Death Penalty or Has Moratorium on Executions

Death Penalty Usage Remains Near Record Lows

Posted on Dec 17, 2019

- Introduction

- Legislative and Executive Actions

- Federal Death Penalty

- Execution and Sentencing Trends

- Innocence

- Problematic Executions

- Problems With New Death Sentences

- Public Opinion and Election of Reform Prosecutors

- Changes to Death Row Conditions

- U.S. Supreme Court

- Key Quotes

- Downloadable Resources

Key Findings

- New Hampshire becomes 21st state to abolish the death penalty

- California imposes moratorium on executions

- Gallup Poll: Most Americans (60%) prefer life without parole to the death penalty

- For the fifth straight year, fewer than 30 people were executed and fewer than 50 people were sentenced to death

- 32 states have no death penalty or have not carried out an execution in more than a decade

Introduction Top

Death Row By State†

| State | 2019 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| California | 729 | 740 |

| Florida | 348 | 353 |

| Texas | 224 | 232 |

| Alabama | 177 | 191 |

| Pennsylvania | 154 | 160 |

| North Carolina | 144 | 144 |

| Ohio | 140 | 144 |

| Arizona | 122 | 121 |

| Nevada | 74 | 75 |

| Nevada | 74 | 75 |

| Louisiana | 69 | 71 |

| U.S. Fed. Gov’t | 61 | 63 |

| Tennessee | 56 | 62 |

| Georgia | 51 | 56 |

| Oklahoma | 46 | 49 |

| Mississippi | 44 | 47 |

| South Carolina | 40 | 39 |

| Oregon | 32 | 33 |

| Arkansas | 32 | 31 |

| Kentucky | 30 | 32 |

| Missouri | 24 | 25 |

| Nebraska | 12 | 12 |

| Kansas | 10 | 10 |

| Indiana | 9 | 12 |

| Utah | 8 | 9 |

| Idaho | 8 | 9 |

| U.S. Military | 4 | 5 |

| Colorado | 3 | 3 |

| Virginia | 3 | 3 |

| South Dakota | 2 | 3 |

| Montana | 2 | 2 |

| New Hampshire^ | 1 | 1 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 1 |

| New Mexico^^ | 2 | |

| TOTAL | 2,656‡ | 2,738‡ |

^New Hampshire abolished the death penalty May 30, 2019

^^New Mexico abolished the death penalty March 18, 2009. On June 18, 2019 a state supreme court ruling vacated the death sentences of the two remaining prisoners on death row and directed that they be resentenced to life in prison

† Data from NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund for July 1 of the year shown

‡ Persons with death sentences in multiple states

are only included once

Capital punishment continued to wither across the United States in 2019, disappearing completely in some regions and significantly eroding in others. New Hampshire became the 21st state to abolish the death penalty and California became the fourth state with a moratorium on executions. With those actions, half of all U.S. states have abolished the death penalty or now prohibit executions, and no state in New England authorizes capital punishment at all.

The use of the death penalty remained near historic lows, as states conducted fewer than 30 executions and imposed fewer than 50 new death sentences for the fifth year in a row. Seven states executed a total of 22 prisoners in 2019. Thirty-four new death sentences were imposed, marking the second-lowest number in the modern era of capital punishment.

In the Midwest, Ohio suspended executions in the wake of a court decision comparing its execution process to waterboarding, suffocation, and being chemically burned alive. On December 11, Indiana marked the ten-year point without an execution. Death sentences in the American West set a record low, Oregon substantially limited the breadth of its death-penalty statute, and — also for the fifth straight year — no state west of Texas carried out any executions. 32 U.S. states have now either abolished the death penalty or have not carried out an execution in more than a decade.

Public opinion continued to reflect a death penalty in retreat. Support for capital punishment remained near a 47-year low and 60% of Americans — a new record — told Gallup they preferred life imprisonment over the death penalty as the better approach to punishing murder.

While most of the nation saw near-historic lows in death sentences and executions, a few jurisdictions bucked the national trend. Death sentences spiked in Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), Ohio to three in 2019 and five in the last two years, more than in any other county in the country. The U.S. government attempted to restart federal executions after a 16-year hiatus, using an execution protocol that had not been submitted to the public for comment or the courts for review. However, its plan to carry out five executions in a five-week period fizzled when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to disturb a lower court injunction temporarily halting the executions.

The stories behind the cases in which executions were carried out or new death sentences were imposed belied the myth that the death penalty is reserved for the worst of the worst. Every prisoner executed in 2019 had either a significant mental impairment (mental illness, brain damage, or chronic trauma), a serious innocence claim, or demonstrably faulty legal process. Those sentenced to death this year included defendants whose juries did not unanimously recommend a death sentence, a brain-damaged defendant who was permitted to represent herself, a foreign national who waived his right to consular assistance, and others who waived their right to counsel, waived their right to a jury trial, and/or pled guilty and presented no case for life.

Executions continued to be geographically isolated, with 91% of all executions taking place in the South, and 41% in Texas alone. Scott Dozier, a mentally ill death-row prisoner who gave up his appeals and unsuccessfully attempted to force Nevada to execute him, committed suicide on death row.

Issues of innocence remained at the forefront of national capital punishment practices. Three more former death-row prisoners were exonerated in 2019, increasing the number of documented U.S. death-row exonerations to 167. Two exonerations came in cases from the 1970s, highlighting the failure of the normal judicial review process to meaningfully protect the innocent. 2019 threatened to be the year of executing the innocent. The risk of wrongful executions drew public attention and outcry in the cases of James Dailey and Rodney Reed, who faced execution dates despite powerful evidence of innocence. But in less highly publicized cases, two other prisoners with evidence of probable innocence were executed. As new evidence pointing to a different killer emerged, Tennessee refused to conduct available DNA testing that had the potential to exonerate a man it may have wrongfully executed in 2006.

There were two humanitarian grants of clemency in 2019, as outgoing Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin commuted the death sentences of one prisoner whose case was plagued by what a federal appeals judge described as “unfairness and abysmal lawyering” and another whose personal transformation on death row was so remarkable, the governor said his “powerful voice needs to be heard by more people.”

In an unusually rancorous Supreme Court year, the Justices sparred over the circumstances in which stays of execution should be granted. The Court ruled that potentially torturous executions were not unconstitutional unless they involved “superadded pain” and the prisoner — even if impeded by state secrecy practices — proved that an established and less painful alternative method to execute him was available to the state. There were few decisions on the substance of death penalty law and the term was more notable for significant allegations of discriminatory practices that the Court chose not to review.

Legislative and Executive Actions Top

The national movement away from the death penalty continued in 2019, as one state abolished its death penalty, another imposed a moratorium on executions, and a third drastically limited the circumstances in which the death penalty may be imposed.

On May 30, 2019, New Hampshire became the 21st state to abolish the death penalty when its legislature overrode Governor Chris Sununu’s veto of a repeal bill. With New Hampshire’s repeal, all of New England and a contiguous band of states from Maine to West Virginia have ended capital punishment. Only one northeastern state — Pennsylvania — still has a death penalty law on its books, and it has a moratorium on executions. The New Hampshire state legislature had passed an abolition bill in 2018, but lacked the two-thirds majority in the Senate to override Sununu’s veto. With bipartisan support, the legislative veto override succeeded in 2019. Rep. Renny Cushing, a sponsor of the bill and family member of two murder victims, said, “I think it’s important the voices of family members who oppose the death penalty were heard, the voices of law enforcement who recognize that the death penalty doesn’t work in terms of public safety, and the voices of the people in the state that know the death penalty is an abhorrent practice were all heard today by the Legislature.”

California Governor Gavin Newsom announced on March 13 that he was halting all executions in the state, which has the nation’s most populous death row. Newsom called the death penalty “a failure” and cited racial discrimination, lack of deterrent value, and the high cost of capital punishment as reasons for the moratorium. California joined Colorado, Oregon, and Pennsylvania as states with governor-imposed moratoria on executions, placing more than one-third (34.1%) of all U.S. death-row prisoners under a moratorium. Newsom also ordered the withdrawal of the state’s proposed execution protocol and the dismantling of the execution chamber at San Quentin prison.

Half of all states have now either abolished the death penalty or have a moratorium on executions. Those states comprise a majority (50.4%) of the U.S. population.

The New Mexico Supreme Court vacated the death sentences of the two men remaining on the state’s death row ten years after New Mexico prospectively abolished the death penalty. By a 3 – 2 vote, a majority of the sitting justices found that the death sentences of Timothy Allen and Robert Fry violated the proportionality requirements of New Mexico’s death-penalty statute, which directs that “the death penalty shall not be imposed if … the sentence of death is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases.”

Oregon, which has had a moratorium on executions in place since 2011, enacted a law narrowing the classes of crimes that are eligible for capital punishment. The new law, signed on August 1, reduces the number of death-eligible categories of “aggravated murder” from 19 to four. The death penalty can now only be imposed in cases involving acts of terrorism in which two or more people are killed, premeditated murders of children aged thirteen or younger, prison murders committed by those already incarcerated for aggravated murder, and premeditated murders of police or correctional officers.

Arizona also reduced the number of death-eligible crimes, eliminating two aggravating circumstances that had repeatedly been challenged as vague or overbroad and one that had never been used. The repealed provisions were that the defendant “knowingly created a grave risk of death” to someone in addition to the murder victim; that the murder was committed “in a cold, calculated manner without pretense of moral or legal justification”; and that the defendant “used a remote stun gun or an authorized remote stun gun in the commission of the offense.” The legislature also combined two other aggravating circumstances into a single new aggravator.

Wyoming saw unprecedented movement toward abolition, with strong bipartisan support. In each legislative house, the lead sponsor of a bill to abolish the death penalty was a Republican. The Wyoming House of Representatives passed the bill on a 36 – 21 vote, and it passed a Senate committee 5 – 4. The bill was defeated in the full Senate by an 18 – 12 vote, but not before receiving the support of a majority of House Republicans and 1/3 of the Republicans in the state Senate.

A bill to abolish the death penalty in Colorado passed a Senate committee, but was withdrawn by the sponsor before further action by the full Senate.

In response to a federal judge who compared Ohio’s lethal injection protocol to waterboarding, suffocation, and chemical fire, Governor Mike DeWine halted executions until the state could develop a new execution protocol that could be approved by courts. “Ohio is not going to execute someone under my watch when a federal judge has found it to be cruel and unusual punishment,” Governor DeWine said in February. The governor granted reprieves of six execution dates over the course of the year.

Nine state legislatures considered measures to ban the execution of individuals with severe mental illness. The Ohio House of Representatives passed such a bill in June, but the Senate did not consider it before adjourning. In Virginia, a severe mental illness exemption passed the state Senate 23 – 17, but did not receive a vote in the House of Delegates.

Alabama and Tennessee both passed new laws expanding the death penalty. Alabama added murder of a first responder as a death-eligible crime. Tennessee added the sale or distribution of opiates with the intent and premeditation to commit murder as an aggravating circumstance for the imposition of the death penalty or life without parole. Tennessee also altered the death-penalty appeals process, removing the appeal to the court of criminal appeals in death penalty cases and providing for automatic direct review by the Tennessee Supreme Court. Arkansas broadened its execution secrecy law, concealing information about the sources of its execution drugs and making it a felony to “recklessly disclose” that information.

In his last series of acts before leaving office, outgoing Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin commuted the death sentences of Gregory Wilson and Leif Halvorsen to terms of life with the possibility of parole.

Wilson was convicted in 1988 in a proceeding one federal appeals judge called “one of the worst examples I have ever seen of the unfairness and abysmal lawyering that pervade capital trials.” Wilson was represented by a lawyer who took the case for free after other lawyers refused to accept appointment for the $2,500 maximum fee then available in the state. His lawyer reportedly had no office and no law books, and the phone number on his business card was the phone number of a local tavern. Defense counsel conducted virtually no cross-examination of the state’s witnesses and presented no evidence in the penalty phase of the trial. Wilson, who is black, was sentenced to death, while his white co-defendant who admitted to being the killer was sentenced to a term of years and is now out of prison. Bevin wrote that, though Wilson had been involved in a “brutal murder,” “to say his legal defense was inadequate would be the understatement of the year.”

Governor Bevin commuted Halvorsen’s sentence after reviewing a clemency petition detailing what his lawyer called a “unique and inspiring story of redemption.” During his 36 years on Kentucky’s death row, Halvorsen went from being a drug addict to a college graduate mentoring at-risk youths. He completed two college degrees while on death row, raised money for underprivileged children, and was the only death-row prisoner the warden trusted to be part of a panel of prisoners who spoke with troubled students. Several of those students wrote letters supporting his petition, saying he helped them to turn their lives around. Halvorsen was also credited with restoring calm in the prison and preventing attacks on corrections personnel and other prisoners. In his commutation order, Gov. Bevin wrote, “Leif has a powerful voice that needs to be heard by more people.”

Federal Death Penalty Top

On July 25, 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) abruptly announced its intention to resume federal executions after a 16-year hiatus. The announcement said that the DOJ had directed the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to adopt a new single-drug lethal-injection protocol to carry out executions using pentobarbital. The DOJ did not provide the public notice or an opportunity to comment on the proposal or follow the rulemaking procedures set forth under federal law before ordering the BOP to adopt this protocol. And although a federal lawsuit challenging the government’s execution procedures was already underway, the government issued death warrants against five prisoners who were not part of that lawsuit, scheduling their executions over a five-week period in December 2019 and January 2020. The first three executions were set for a five-day span between December 9 and 13.

The announcement sparked strong reactions against resuming federal executions from correctional officials, religious leaders, retired judges and prosecutors, and victims’ families. Despite Attorney General William Barr’s assertion that “we owe it to the victims and their families to carry forward the sentence imposed by our justice system,” family members in two of the cases had long opposed the government’s pursuit of the death penalty.

Earlene Peterson, whose daughter and granddaughter were killed in the robbery/murders for which Daniel Lee was scheduled to be executed on December 9, released a video asking for clemency for Lee. In the video, Peterson said, “I can’t see how executing Daniel Lee will honor my daughter in any way. In fact, it’s kind of like it dirties her name, because she wouldn’t want it and I don’t want it. That’s not the way it should be. That’s not the God I serve.” Peterson was joined in her plea by a surviving daughter and granddaughter, as well as by the trial judge and the trial prosecutor, both of whom noted that the more culpable ringleader who had killed Peterson’s granddaughter had been sentenced to life.

Lezmond Mitchell and his victims were members of the Navajo Nation, and the case involved a murder on Navajo lands. The victims’ family members and tribal authorities had long opposed seeking the death penalty in the case. In addition, although DOJ had said that the prisoners had exhausted all available appeals, Mitchell still had a case pending before a federal appeals court when his death warrant was signed, and that court halted his execution so it could consider his claim of anti-Native American bias throughout his trial.

175 family members of murder victims signed a letter calling for the DOJ and the President to halt the executions and urging them to reinvest the many millions of dollars “waste[d]” on the death penalty “in programs that actually reduce crime and violence and that address the needs of families like ours.” Sixty-five former judges and 59 current and former prosecutors or law enforcement officials joined the victims’ families in opposing the federal executions. The judges wrote: “there are too many problems with the federal death penalty system, and too many unanswered questions about the government’s newly announced execution procedure, to allow executions to proceed.” Twenty-six former corrections officials raised concerns, especially regarding the rushed timeframe of the executions. Former warden Allen Ault wrote that the compressed execution schedule “causes an extended disruption to normal prison operations and precludes any attempt to return to normalcy following an execution. It also prevents any meaningful review by execution team members and other officials to address problems or concerns in the execution process. That increases the risk that something could go horribly wrong in the next execution. And if a ‘routine’ execution is traumatizing for all involved, a botched one is devastating.”

On November 20, a federal district judge issued a preliminary injunction blocking the executions, saying the DOJ had “exceeded its statutory authority” in setting the new execution protocol. The DOJ appealed the order and asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to lift the injunction and let the executions proceed while its appeal of the injunction was pending. The appeals court denied the DOJ’s request, and the DOJ then asked the U.S. Supreme Court to lift the injunction. The Supreme Court declined, ensuring that the executions could not proceed as originally scheduled. The Supreme Court directed the appeals court to resolve the government’s appeal of the injunction “with dispatch,” leaving open the competing possibilities that the injunction could be vacated and new execution dates could be issued within several months or that new warrants could not be issued until the federal courts fully address the merits of the federal death-row prisoners’ challenges to the legality and constitutionality of the federal execution protocol.

Execution and Sentencing Trends Top

Executions By State

| State | 2019 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | 9 | 13 |

| Tennessee | 3 | 3 |

| Alabama | 3 | 2 |

| Georgia | 3 | 2 |

| Florida | 2 | 2 |

| South Dakota | 1 | 1 |

| Missouri | 1 | |

| Nebraska | 1 | |

| Ohio | 1 | |

| TOTAL | 22 | 25 |

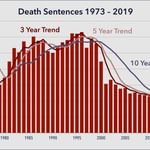

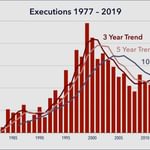

Executions and new death sentences remained near historic lows in 2019, marking the fifth consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions and fewer than 50 new death sentences.

States carried out 22 executions in 2019, the second fewest in 28 years. The only year since 1991 in which states conducted fewer executions was 2016, when 20 prisoners were put to death. Executions were more than 77% below the peak of 98 twenty years ago, and were down slightly from the 25 executions conducted in 2018.

Death sentences also remained near record lows in 2019. Eleven states and the U.S. federal government imposed a total of 34 new death sentences, the second fewest in the modern history of the U.S. death penalty.[1] New death sentences declined by 20.9% in 2019 from the already low 43 new death sentences imposed in 2018, and were down more than 89% from the peak of 310 or more new death sentences imposed each year from 1994 through 1996. The only time in the past 47 years in which fewer defendants were sentenced to death was 2016, when 31 new death sentences were imposed.

Counties With the Most Death Sentences in the Last Five Years

| County | State | New Death Sentences 2015 – 2019 | New Death Sentences 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riverside | California | 16 | 2 |

| Los Angeles | California | 10 | |

| Maricopa | Arizona | 9 | |

| Clark | Nevada | 7 | |

| Cuyahoga | Ohio | 6 | 3 |

| Mobile | Alabama | 5 | |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma | 5 | |

| Orange | California | 4 |

For both executions and new death sentences, the death penalty became increasingly geographically isolated in 2019. Most states neither performed an execution nor imposed a death sentence. Only 15 states, plus the federal government, sentenced any defendant to death or executed any prisoner. Only four jurisdictions (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Texas) did both.

Indiana conducted no executions for the tenth consecutive year, bringing to 11 the number of death-penalty states to have gone more than a decade without an execution. Arizona conducted no executions for the fifth consecutive year, making it the 17th death-penalty state with at least a five-year hiatus on executions. Overall, 32 states, plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the federal government, and the U.S. military now have no death penalty or have had no executions for more than a decade. Thirty-eight have either no death penalty or no executions in the past five years.

Once again, the vast majority (91%) of U.S. executions took place in the South, with 41% in Texas alone. For the fifth consecutive year, no executions were performed by any state west of Texas.

[1] The modern era of the U.S. death penalty dates back to 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all existing death-penalty statutes and states began re-enacting new capital punishment laws in 1973.

Courts halted more executions in 2019 (24 stays or injunctions) than states carried out (22). Of the 65 scheduled execution dates set in 2019, nearly two-thirds (66%) did not go forward. Thirteen prisoners, all in Ohio, received reprieves as a result of lethal-injection concerns. Three death warrants scheduled for 2019 were directed at prisoners who subsequently died on death row. These included a death warrant in Ohio rescheduling the execution of terminally ill Alva Campbell after the state called off his botched execution attempt in November 2017.

The 24 stays were granted for reasons ranging from irregularities in the issuance of the warrant, to concerns about the prisoner’s mental competency, to claims of innocence. In a carryover from 2018, Nevada death-row prisoner Scott Dozier, who had persuaded the state courts that he was not suicidal and was competent to waive his appeals, committed suicide on death row just months after a court halted his execution because of Nevada’s misconduct in obtaining the execution drugs.

New death sentences were imposed in 11 states in 2019, but only eight states had more than one. Florida imposed seven death sentences, more than any other state. However, in the four years before the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Florida’s non-unanimous sentencing statute in 2016, the state averaged 13.75 new death sentences per year. In the four years since, it has averaged 5 sentences per year. Ohio, where executions are on hold because of problems with the lethal-injection protocol, imposed the second most sentences, with six. Cuyahoga County (Cleveland) alone accounted for half of those, matching the total for the entire state of California. Georgia imposed a death sentence for the first time in five years, after the trial court permitted Tiffany Moss — a defendant with documented brain damage — to represent herself. Moss presented no defense at either the guilt or penalty phases of her trial.

The West set a record low for the number of death sentences imposed in the region, with only four sentences, half the previous record low of eight, set in 2018. California imposed just three new death sentences in 2019, the fewest in any year since the state reinstated capital punishment in 1978. Arizona imposed one new death sentence, matching that state’s record low.

Thirty counties (fewer than 1% of all U.S. counties) and one federal district imposed death sentences in 2019, and only two counties (Cuyahoga, Ohio and Riverside, California) imposed more than one.

Innocence Top

Questions of the adequacy of judicial review to protect the innocent stood out boldly in 2019, as five innocent men obtained their freedom after decades in prison and at least four others who are likely innocent were executed or temporarily escaped execution.

Three men who were wrongfully convicted and sentenced to die were exonerated in 2019. Two had been convicted in 1976 and spent more than 40 years in prison. A third was freed after a conviction integrity unit released documents showing that since-fired prosecutors had withheld exculpatory evidence. Their exonerations brought to 167 the number of former death-row prisoners exonerated in the United States since 1973.

Clifford Williams, Jr. was released from prison in Florida in March. Williams’ defense counsel ignored 40 alibi witnesses who could have testified that he and his 18 year-old nephew and co-defendant, Nathan Myers, had been attending a party next door at the time of the crime. Duval County Conviction Integrity Review Director Shelley Thibodeau noted that no physical evidence linked either Williams or Myers to the crime, and the forensic evidence flatly contradicted the supposed “eyewitness” testimony of a key prosecution witness. The jury in the case recommended a life sentence for both men, but Judge Cliff Shepard overrode the recommendation for Williams and imposed a death sentence. Florida leads the nation in death-row exonerations, and in 21 of the 23 exonerations for which the jury’s sentencing recommendation is known, the jury either recommended a life sentence or was not unanimous in recommending death.

In June, Charles Ray Finch was exonerated in North Carolina, following a federal court ruling that he had proven his “actual innocence.” Like Williams, Finch had been convicted in 1976 by false eyewitness testimony. At the time, North Carolina law carried a mandatory death sentence, and the statute was declared unconstitutional shortly after Finch’s conviction. That court decision likely saved Finch’s life, because after more than 25 years of appeals, he had no legal remedies left. Then, Finch obtained the assistance of the wrongful conviction clinic at Duke Law School, which worked for another 15 years to secure his freedom. The clinic’s students and volunteers discovered that police had pressured witnesses to testify against Finch and that a key witness had undisclosed alcoholism and cognitive problems that included difficulty with short-term memory. They also uncovered evidence that police had manipulated eyewitness identification lineups by dressing Finch in the same type of clothing the perpetrator had been described as wearing and that the police then lied about their misconduct.

In December, after the initial publication of this report, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office Conviction Integrity Unit filed a motion to drop charges against Christopher Williams, who had been on Pennsylvania’s death row since 1993. Williams had won a new trial in 2013 based on his trial counsel’s ineffectiveness for failing to investigate the crime-scene evidence and present available medical and forensic evidence that would have shown that the testimony of the only witness linking Williams to the murder was physically impossible. When the Conviction Integrity Unit reviewed the case file, it found “a plethora of significant material, exculpatory evidence” that two later-fired prosecutors had not disclosed to the defense. That evidence, the CIU said, contradicted the alleged eyewitness testimony, impeached other prosecution witnesses, implicated other uncharged suspects, and suggested that the three victims had been involved in an ongoing dispute between “two extremely violent gangs, either of which may have been responsible for their deaths.”

Two additional prisoners who had been wrongfully capitally prosecuted obtained their release from prison in 2019, but without full exonerations. Louisiana prisoner Elvis Brooks was capitally tried in 1977 for a barroom murder, but was sentenced to life in prison. No physical evidence linked him to the murder, and he presented twelve alibi witnesses who testified that he was elsewhere when the murder occurred. The sole evidence against Brooks came from cross-racial identifications by three white strangers who had been inside the dimly lit bar during the crime and who had picked out a photograph of Brooks from a police photo array. Brooks’ conviction was overturned, and prosecutors insisted he agree to a plea deal as a condition to securing his immediate release. Brooks’ lawyer from the Innocence Project New Orleans, Charrel Arnold, said: “Mr. Brooks never sought a plea agreement. It is deeply unfair that an innocent man would be forced to choose between entering a plea to secure his immediate freedom and waiting years more in prison to prove his innocence through litigation.” Charrel Arnold called Brooks’ plight “particularly unfair given that the state has known about the new evidence presented in this case since 1977.”

In August 2019, a Nevada trial court ordered the state to release death-row prisoner Paul Browning, although Las Vegas prosecutors are still appealing the order dismissing the charges against him. Browning had been represented at his 1986 trial by a lawyer who had been practicing criminal defense for less than a year and who never interviewed the police who responded to the scene, never examined the evidence against Browning, and failed to investigate the crime. In his post-conviction appeal, Browning presented evidence that police and prosecutors had withheld evidence of a bloody footprint found at the scene that did not match Browning’s shoes or foot size, misrepresented blood evidence in the case, manipulated eyewitness testimony, and failed to disclose benefits offered to a key witness who may have committed the murder and framed Browning.

Four prisoners who were scheduled for execution in 2019 also raised significant innocence claims. Domineque Ray was executed in Alabama on February 7. Though most of the attention devoted to his case focused on questions of religious discrimination (discussed below), he also argued that he was innocent and that the evidence against him was unreliable. Ray was convicted and sentenced to death for the rape and murder of a 15-year-old girl. No physical evidence linked him to the crimes, and a sole prosecution witness, Marcus Owden, implicated Ray. In 2017, Ray’s appeal lawyers discovered for the first time that Owden — who avoided the death penalty by testifying against Ray — had schizophrenia and was suffering from delusions and auditory hallucinations when he accused Ray of the rape and murder and testified against him. Ray’s lawyers argued that the prosecution’s deliberate suppression of this evidence, despite being aware of Owden’s mental illness, violated due process rights and entitled Ray to a new trial. Without comment, the Supreme Court declined to review the claim and denied a stay.

The forensic evidence against Texas prisoner Larry Swearingen was so weak that his defense attorney called it “quackery.” Numerous forensic experts contradicted the testimony used to convict Swearingen. The “smoking gun” in the case — a piece of pantyhose that allegedly matched the pantyhose used to strangle the victim — was not discovered in two initial searches of Swearingen’s home, and was “found” only after the victim’s body had been discovered with a pantyhose ligature around her neck. The lab technician who testified at trial that the two pieces were halves of a single pair of pantyhose had initially found “no physical match” between them. Four forensic pathologists, three forensic entomologists, and a forensic anthropologist contradicted the medical examiner’s testimony on the time of death. Under the medical examiner’s timeline, the victim had been killed immediately after her disappearance. All of the other experts concluded she had been dead at most two weeks before her body was discovered. Because Swearingen had been arrested three weeks before the body was found and had remained in police custody, it would have been impossible for him to have committed the killing. Texas executed Swearingen on August 21.

James Dailey’s November 7 scheduled execution was halted by a Florida federal district court on procedural grounds unrelated to the substance of the serious innocence issues presented in his case. Dailey presented evidence that his co-defendant, Jack Pearcy, had admitted on at least four separate occasions that he alone had committed the murder. That evidence included a 2017 signed affidavit stating, “James Dailey was not present when Shelly Boggio was killed. I alone am responsible for Shelly Boggio’s death.” No physical evidence linked Dailey to the crime, and the only testimony against him came from Pearcy — who was sentenced to life in prison — and three jailhouse informants to whom police provided information about the murders and who received reductions in the charges in their cases for saying Dailey had confessed to them. A ProPublica/New York Times Magazine story published in December revealed that one of those witnesses, Paul Skalnik, was a serial perjurer whose testimony had put dozens of defendants in jail, including four on death row.

Texas death-row prisoner Rodney Reed received a stay of execution from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals on November 15, just five days before his scheduled execution. The stay order directed the Bastrop County district court to review Reed’s claims that prosecutors presented false testimony and suppressed exculpatory evidence in his case and that Reed is actually innocent. Hours before the court issued the stay, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles unanimously recommended that Gov. Greg Abbott grant a 120-day reprieve of Reed’s execution. Reed’s innocence claim received an unprecedented outpouring of support from Texas elected officials across the political spectrum, high-profile celebrities, legal organizations, and diplomats. A petition to halt the execution garnered three million signatures. Reed’s attorneys sought DNA testing of evidence from the case, including the belt used to strangle the victim, Stacey Stites. Reed, who is black, says he and Stites, who is white, were having an affair that they kept secret because their interracial relationship would have caused a scandal in their small Texas town. He presented numerous affidavits pointing to Stites’ fiancé, Jimmy Fennell, an Austin-area police officer, as the killer. Witnesses said they had heard Fennell on several occasions threaten to kill Stites if she cheated on him, including saying “he would strangle her with a belt.” Fennell was fired from his police job following his arrest and conviction for kidnapping a woman while on duty and sexually assaulting her. According to court filings by the Innocence Project, “prominent forensic pathologists” have concluded Fennell’s testimony that Stites was abducted and killed on her way to work is “medically and scientifically impossible.”

Innocence issues reached into the grave as well. In Tennessee, April Alley, whose father Sedley Alley was executed in 2006 on charges that he had raped and murdered Suzanne M. Collins, asked the state courts to conduct posthumous DNA testing that Alley and her lawyers from the Innocence Project argued could prove his innocence. On November 18, however, the trial court dismissed her request. Alley had consistently said he had been coerced into confessing to the crime, and his supposed confession was inconsistent with the physical evidence in the case. The Tennessee Supreme Court had denied Alley’s request for DNA testing prior to execution, but in an opinion in another case after Alley had been executed, the court acknowledged they had wrongly denied his request. Innocence Project co-founder Barry Scheck said, “This case has all the tell-tale signs of a wrongful conviction — a confession that has been demonstrated to be false by objective forensic evidence, mistaken eyewitness identification, and, most disturbing, the refusal to test DNA evidence that could have exonerated Mr. Alley or removed the doubts about his guilt.” In dismissing the request for DNA testing, Judge Paula Skahan said that Alley’s estate did not have standing under Tennessee law to request the testing.

Problematic Executions Top

The executions in 2019 raised troubling issues of fairness and the persistent inability or unwillingness of states and the courts to limit capital punishment to the most serious murders and the most culpable defendants. At least 19 of the 22 prisoners who were executed this year had one or more of the following impairments: significant evidence of mental illness (9); evidence of brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range (8); or chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse (13). Many cases that resulted in execution in 2019 also involved faulty and insufficient legal process or flagrantly arbitrary outcomes. Once again, this year’s executions did not represent the “worst of the worst” crimes and offenders, but the most vulnerable defendants and those whose trials and appeals were the least reliable.

Four of the executed prisoners were under age 21 at the time of their crime, placing them in a category that neuroscience research has shown is functionally indistinguishable, in terms of brain development and executive function, from juvenile offenders who are exempt from execution.

Five prisoners presented claims that a co-defendant was the more culpable perpetrator. Marion Wilson and his co-defendant, Robert Earl Butts, were tried separately in Georgia. Believing that Butts was the shooter, the prosecutor offered 19-year-old Wilson (but not Butts) a plea deal that would avoid the death penalty. Wilson turned down the deal. In each trial, the prosecutor then argued to the jurors that the defendant in front of them was the triggerperson. Although the evidence all pointed to Butts as the shooter, both men were sentenced to death.

Ray Cromartie, who was executed in Georgia in November, admitted that he was involved in the robbery in which a store clerk was killed but maintained that he was not the shooter. The prosecution argued that he was the killer and should be sentenced to death. Supported by the murder victim’s daughter, Cromartie sought a stay of execution to permit DNA testing of shell casings, clothing, and a cigarette pack from the crime scene that forensic experts said could prove that he was not the shooter. Elizabeth Legette urged the Georgia Supreme Court to permit DNA testing. She wrote: “My father’s death was senseless. Executing another man would also be senseless, especially if he may not have shot my father. … [T]he State has set a date to execute Mr. Cromartie without doing any testing. This is wrong, and I hope that you will take action to make sure that the testing happens.”

The prisoners executed this year were also subject to faulty legal process ranging from non-unanimous sentencing recommendations to juror bias to false or misleading testimony.

Robert Jennings, the first person executed in the U.S. in 2019, was sentenced to death under a statute that was later declared unconstitutional because it did not allow full consideration of mitigating evidence. The jury instructions given in his case to redress that error were also later declared unconstitutional, and 25 Texas death-row prisoners had their death sentences overturned as a result. However, Jennings’s court-appointed trial and appeal lawyers failed to raise the issue in Texas state court, and the Texas federal courts refused to consider the issue on the grounds that the state court lawyers had procedurally defaulted the claim. Jennings’ state court lawyers also failed to investigate and present evidence that he had history of brain damage from a car crash and an injury with a baseball bat; an IQ of 65 with related intellectual and adaptive deficits; that he was born as the result of a rape and reared in an impoverished, abusive, and neglectful home environment in which his mother frequently told him she did not want him.

Domineque Ray, executed in Alabama, was sentenced by a non-unanimous jury (11 – 1). He raised innocence claims, had numerous overlapping mental impairments, and was denied access to his spiritual advisor at the time of his execution. Under Alabama law, Christian chaplains could accompany prisoners into the execution chamber. Prisoners of other faiths, including Ray, who was Muslim, could not have their religious advisors present in the execution chamber. Ray sought to challenge the policy before the U.S. Supreme Court, but his request was denied as untimely, despite the vociferous dissent of four justices. The Court’s decision was met with criticism from across the political spectrum and from religious leaders. Less than two months later, the Court intervened to halt the execution of Texas prisoner Patrick Murphy, a Buddhist who had raised a religious discrimination claim almost identical to Ray’s. Murphy challenged Texas’ policy that allowed the prison’s chaplains, who were only Christian or Muslim, in the execution chamber, but blocked other religious advisors.

Three Texas prisoners — Billie Wayne Coble, Robert Sparks, and Travis Runnels — were sentenced to death based upon false testimony by prison investigator A.P. Merillat, who worked with Texas prosecutors as an expert witness on conditions of incarceration and the likelihood that defendants could commit future acts of violence in the conditions in which they would be imprisoned. In at least 15 capital trials, Merillat falsely asserted that prisoners convicted of capital murder would be “automatically” placed in mid-level security, where they would be in frequent contact with prison guards and non-violent offenders. He also falsely claimed that “If [a defendant] had prior convictions … the prison is not going to look at those previous convictions” in determining the type of facility in which the prisoner would be incarcerated. Merillat’s testimony repeatedly overstated the frequency of prison violence and falsely claimed that loopholes would allow life-sentenced prisoners to commit violence. In 2012, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed two death sentences as a result of Merillat’s prejudicially false testimony, but neither it nor the federal courts intervene in these three cases.

Texas prisoner John William King was sentenced to death for his involvement in the lynching death of James Byrd. King maintained that his co-defendants committed the murder and that he was not present when it occurred. His trial lawyers, however, refused to present his innocence claim. His appellate attorneys argued unsuccessfully that the trial attorneys’ actions violated the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling in McCoy v. Louisiana. Judge Michael Keasler joined by three other judges of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, wrote: “A death-sentenced man who has asserted his innocence since his capital-murder trial has asked us to review his claim that his trial lawyer overrode his express wishes to pursue a defense consistent with his innocence. In light of … the horrible stain this Court’s reputation would suffer if King’s claims of innocence are one day vindicated (or, perhaps, if the Supreme Court eventually decides that McCoy should apply retroactively), I think we ought to take our time and decide this issue unhurriedly. I would grant the stay.” Later in the year, Stephen Barbee received a stay of execution on a similar McCoy claim.

Florida executed Gary Ray Bowles, despite the fact that no court had ever addressed his claim that he was therefore ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability (ID). Bowles’ lawyers did not initially file a claim of intellectual disability because the Florida Supreme Court had ruled that a person whose IQ was higher than 70 could not be considered intellectually disabled, even if they met all the other criteria for an ID diagnosis. After the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the 70-IQ cutoff as unconstitutional, Bowles’ new lawyers presented evidence that his IQ of 74 was within the clinically accepted range for intellectual disability and that he had classic adaptive deficits associated with ID. The Florida Supreme Court ruled that his petition was untimely and that he should have raised his claim during the time in which the Florida courts would have summarily rejected it because of his IQ score.

Charles Rhines was sentenced to death by a South Dakota jury that relied on anti-gay stereotypes in reaching its verdict. According to juror affidavits, there was “lots of discussion of homosexuality” during jury deliberations after jurors learned that Rhines was gay. One juror said “[t]here was a lot of disgust. … There were lots of folks who were like, ‘Ew, I can’t believe that.’” In a 2016 sworn statement, juror Frances Cersosimo reported that another juror had said, “If he’s gay, we’d be sending him where he wants to go” by sentencing Rhines to life in an all-male prison. Juror Harry Keeney said in a sworn statement, “We also knew he was a homosexual and thought he shouldn’t be able to spend his life with men in prison.” In 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado that “where a juror makes a clear statement that indicates he or she relied on racial stereotypes or animus to convict a criminal defendant, the Sixth Amendment requires … the trial court to consider the evidence of the juror’s statement and any resulting denial of the jury trial guarantee.” Rhines’ lawyers argued that the court should apply this same principle to bias based on sexual orientation. He was executed after the state and federal courts refused to consider his claim of juror bias and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his case.

Lee Hall Jr. was also executed despite a strong claim of juror bias that was never considered by a court. Hall was convicted of killing his ex-girlfriend in an act of domestic violence. Potential jurors were questioned on their past experiences related to domestic violence, but one juror came forward years later and revealed that she had not disclosed that she had been raped and physically abused by her former husband. Because of her history, she said in an affidavit, “[a]ll these memories [of abuse] flooded back to me” during the trial, “I could see myself in Traci [Crozier]’s shoes, given what happened to me. I hated Lee for what he did to that girl.” Two weeks before Hall asked the Tennessee courts to stay his execution, another Tennessee prisoner who was sentenced to death for a murder involving domestic violence was granted a new trial because a juror in his case had not disclosed her history of domestic abuse. Although the issues in the two cases were virtually identical, the Tennessee courts refused to consider Hall’s claim.

Texas scheduled 13 executions in the last five months of the year, many of which were the embodiment of unfair legal process. Six of those executions were stayed and one warrant was withdrawn. Dexter Johnson received a stay to consider his claim of intellectual disability, which had previously been rejected under an unscientific and unconstitutional standard formerly used in Texas. Stephen Barbee was granted a stay because his attorneys had refused to present his innocence claims. Randy Halprin, a Jewish prisoner, received a stay after anti-Semitic comments by his trial judge came to light. Judge Vickers Cunningham, who oversaw Halprin’s trial, had disparaged Halprin as “a f***in’ Jew” and “g**damn k**e,” and made racist comments about Halprin’s Latino co-defendants. Halprin, along with Patrick Murphy, were members of the “Texas 7” who had been sentenced under Texas’ controversial “law of parties,” a law that allows defendants to be sentenced to death based upon the actions and intent of others, if the defendant played even a small role in a crime that resulted in someone’s death. Murphy said he was not present when the victim was killed, and Halprin said he did not fire any shots. Randall Mays’ execution warrant was withdrawn to allow a court to consider whether he was incompetent for execution. Ruben Gutierrez maintained he had been involved in a robbery, but had not committed the killing and did not intend that a killing would take place. His execution was stayed because of irregularities in the issuance of his death warrant. Rodney Reed was granted a stay to consider significant evidence of innocence.

On September 20, Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery asked the Tennessee Supreme Court to set execution dates for an unprecedented nine death-row prisoners, the largest execution request in the modern history of Tennessee’s death penalty. On the same day, he attempted to intervene in the case of death-row prisoner Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman to undo a court-approved plea deal that had resentenced Abdur’Rahman to three consecutive life sentences and to reinstate a death warrant scheduling his execution for April 2020. Slatery’s actions drew fire from defense lawyers, who described it as a “request for mass executions.” Abdur’Rahman’s lawyers had presented evidence that prosecutor John Zimmerman had discriminatorily excluded black prospective jurors from serving in Abdur’Rahman’s capital trial. Based on these and other misconduct allegations against Zimmerman, Davidson County District Attorney Glenn Funk agreed that justice would be served with Abdur’Rahman’s sentence being reduced to life in prison. Telling the court that “[t]he pursuit of justice is incompatible with deception,” Funk conceded that Abdur’Rahman’s trial had been infected by “overt racial bias.” The Tennessee Supreme Court on December 11 stayed Abdur’Rahman’s execution to determine whether Slatery has authority to intervene in the case.

Problems With New Death Sentences Top

Many of the problematic aspects of the execution cases only came to light years later, after appeal lawyers discovered facts that trial counsel failed to investigate. But even at this comparatively early stage of the cases, a significant number of the death sentences imposed in 2019 paint a troubling picture of the legal process in capital cases.

No state permits non-unanimous jury verdicts at the guilt stage of a capital case and only one — Alabama — still permits a judge to impose the death penalty based upon a jury’s non-unanimous recommendation for death. Data suggests that this practice disproportionally produces death sentences and may increase the risk of wrongful executions. Two of the three people judges sentenced to death in Alabama in 2019 had non-unanimous jury sentencing recommendations. Lionel Francis’ jury voted 11 – 1 for death, while Brett Yeiter’s jury was divided 10 – 2.

Several defendants were sentenced to death after questionable trials in which they waived their right to counsel and represented themselves. In Georgia, a trial court allowed Tiffany Moss to represent herself despite evidence presented by the Office of the Capital Defender that neuropsychological testing showed she had brain damage affecting regions of the brain associated with judgment, decision making, and impulse control. Moss said she would leave her defense to God, and she took no notes, did not actively participate in jury selection, and presented no guilt- or penalty-stage defense. She was the first person sentenced to death in Georgia since 2014.

In Kern County, California, Mexican national Miguel Crespo Cota refused the assistance of the Mexican consulate and the Mexican Capital Legal Assistance Project and represented himself at his trial for killing a transgender cellmate. After the jury unanimously voted for death, Crespo Cota continued to represent himself in the final sentencing hearing before the court, telling the judge “I had a restriction not to be housed with a [gay expletive].” Joseph McAlpin represented himself at trial in Ohio and declared that he would only accept full liberty or death. He got death.

Other defendants facilitated their death sentences by waiving their right to have jurors determine their fate. In Ohio, George Brinkman pled guilty, waived jury sentencing, and was sentenced to death by a three-judge panel. Arron Lawson waived his right to a jury, was convicted in a bench trial, and was sentenced to death by three judges. In Florida, Rocky Beamon waived his jury rights and asked the trial judge to sentence him to death.

Also in Florida, Johnathan Alcegaire instructed his lawyers not to present any evidence during the sentencing phase of his trial. The jury deliberated for just 90 minutes before sentencing him to death. In a sentencing memorandum to the court, his counsel noted that Alcegaire wasn’t the gunman in the crime and that he had not had any behavioral problems in his three years in jail. The court accepted the jury’s recommendation for death.

In Pennsylvania, Jacob Sullivan pleaded guilty and asked the jury to consider the fact that prosecutors had offered his co-defendant a life sentence in exchange for pleading guilty and testifying against Sullivan. Sullivan was sentenced to death.

Public Opinion and Election of Reform Prosecutors Top

Public opinion continued to reflect a death penalty in retreat, as polls showed every demographic group more strongly favoring alternatives to capital punishment and reform prosecutors making further inroads at the ballot box.

The 2019 Gallup poll, conducted in October and released in November, found that, for the first time since Gallup began asking the question in 1985, a majority of Americans chose life imprisonment as a better approach for punishing murder than the death penalty. By a margin of 24 percentage points, respondents said life without parole “is the better penalty for murder.” Sixty percent said they preferred life without possibility of release, while 36% favored the death penalty.

The responses represented a marked 15-percentage-point change in the five years since Gallup last asked the question. In 2014, 50% of respondents said they preferred the death penalty, while 45% preferred life in prison. “This is a pretty dramatic shift in opinion,” Gallup Senior Editor Dr. Jeffrey Jones, who conducted the survey, told the Tulsa World. The shift in preference crossed party lines, with Jones noting, “all key subgroups show increased preferences for life imprisonment. This includes increases of 19 points among Democrats, 16 points among independents, and 10 points among Republicans.” The groups that most strongly preferred life without parole were non-whites (72%), people aged 18 – 34 (68%), women (66%), and college graduates (65%).

When asked in the abstract whether they favored the death penalty or not, 56% of Americans said yes — the same percentage as in 2018 and only one percentage point above the 47-year low recorded in 2017. Opposition to the death penalty reached its highest level in the modern era of capital punishment, with 42% of respondents saying they opposed the practice.

Election results in 2019 reflected the public’s growing embrace of reform prosecutors, as voters in four states elected prosecutors who vowed to reduce or end the use of capital punishment as part of their platforms to fight mass incarceration. Four counties in the Washington, DC suburbs of Northern Virginia elected progressive prosecutors. Newly-elected Commonwealth’s Attorneys Steve Descano of Fairfax County and Parisa Dehghani-Tafti of Arlington County explicitly campaigned against the death penalty. Dehghani-Tafti called it “inhumane, expensive, and racially-biased,” while Descano criticized it as “ineffective at stopping crime, in addition to being prohibitively expensive.” “There is no link between the death penalty and community safety,” Descano said. Amy Ashworth campaigned for office in Prince William County, saying she is “personally against” the death penalty and that its imposition “should be extraordinarily rare.” Ashworth will replace retiring prosecutor Paul Ebert, whose office put more people on death row in his 51-year tenure than any other county in Virginia and accounted for more executions than 99.3% of all U.S. counties. Candidate Buta Biberaj, who won Loudoun County’s race, said that “we have to be very mindful as to how we use [the death penalty] …. Death is final.”

In Southeastern Pennsylvania, Jack Stollsteimer became the first Democrat ever to hold the position of Delaware County District Attorney, joining Larry Krasner in neighboring Philadelphia among the ranks of progressive prosecutors. During the campaign, Stollsteimer had criticized the incumbent for opposing reopening the nearly 40-year-old murder case of Leroy Evans. Evans, who has consistently maintained his innocence, was implicated by a teen offender who had been threatened with the death penalty.

San Francisco voters elected former public defender Chesa Boudin, who ran on an anti-establishment platform of implementing restorative justice, ending mass incarceration, and eschewing the death penalty.

Since 2015, voters have replaced the prosecutors in 11 of the 34 counties with the nation’s largest death rows.

Changes to Death Row Conditions Top

In response to lawsuits or the threat of legal action, four death-penalty states made significant changes to the conditions of incarceration for death-row prisoners in 2019.

In May, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld a lower court’s opinion that Virginia’s former policy of 23- or 24-hour per day solitary confinement for prisoners on death row “created, at the least, a significant risk of substantial psychological or emotional harm” and that the state had been “deliberately indifferent” to that risk. At the time the suit was filed, Virginia had five men on death row and limited them to one hour of recreation per day five days a week and a ten-minute shower three days per week. During recreation, they “were confined to individual enclosures with concrete floors and enclosed by a steel and wire mesh cage.” Under the Commonwealth’s new policy, death-row prisoners are allowed shared recreation every day, outdoor recreation five days a week, daily showers, and weekly contact visits with their families.

A settlement was reached in November between Pennsylvania and the 136 people on death row, ending the Commonwealth’s practice of permanent solitary confinement and now providing prisoners at least 42.5 hours a week out of their cells and 15 minutes of phone access each day, contact visits, outdoor exercise, daily showers, group religious services, jobs, and access to educational programs. Jimmy Dennis, who was released on a plea deal in 2017 after 25 years on Pennsylvania’s death row, said of the conditions he experienced: “It’s like chipping away at your soul on so many different levels, and you feel like you’re literally suffocating in your own skin.”

South Carolina announced in July that it was moving all death-row prisoners to a different facility, saying that the move “will address some of the concerns raised in a recent lawsuit filed on behalf of the Death Row inmates.” Like Virginia, South Carolina had held prisoners in solitary confinement 23 hours a day. In the new facility, death-sentenced prisoners have more opportunities to interact with one another, including holding jobs within their unit.

In response to the threat of legal action by several prisoners’ rights organizations, Oklahoma announced in September that it would relocate “all qualifying death row inmates” out of permanent solitary confinement in an underground facility that one prisoner compared to being “buried alive.” The change will allow for contact visits and access to fresh air and natural light.

U.S. Supreme Court Top

Death penalty rulings in the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 were less notable for rulings on the constitutionality of capital trials and sentencing proceedings than for the deep divisions within the Court on how executions should be carried out and whether court review and particularly stays of execution should be granted.

In Bucklew v. Precythe, the Court declared that “The Eighth Amendment does not guarantee a prisoner a painless death.” In a contentious 5 – 4 decision, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the majority that a method of execution was not unconstitutional unless it involved “superadd[ed] … terror, pain, or disgrace.” As part of that determination, Gorsuch wrote, the prisoner must prove that an established and less painful alternative method to execute him was available to the state — although Missouri’s execution secrecy practices had prevented Bucklew from showing what could be done.

Russell Bucklew had challenged the constitutionality of Missouri’s use of lethal injection as it applied to him because of his rare medical condition, cavernous hemangioma. As a result of that disorder, Bucklew had blood-filled tumors in his head, neck, and throat, that doctors said could rupture during the execution process, potentially causing him to experience excruciating pain and suffocate to death on his own blood. Bucklew proposed execution by nitrogen hypoxia as a less painful method to put him to death.

The decision exposed sharp divisions within the Court and in the Justices’ approaches to litigation seeking stays of execution. On the substance of lethal-injection challenges, the court rejected a requirement that a state must statutorily authorize an execution method before it can be considered “available,” but questioned whether nitrogen hypoxia was a legitimately available alternative, saying Missouri should not be compelled to be the first state to adopt a new, “untried and untested” execution method. In a dissent by Justice Stephen Breyer, the four liberal and moderate Justices criticized the majority for ignoring evidence that “executing Bucklew by lethal injection risks subjecting him to constitutionally impermissible suffering” and “violates the clear command of the Eighth Amendment.” A prisoner who is challenging the cruelty of a particular execution method based solely on his or her unique medical circumstances, they argued, should not be required to identify an alternative method of execution. In a separate dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor called the Court’s approach to lethal-injection cases a “misguided” trip along a “wayward path,” saying “there is no sound basis in the Constitution for requiring condemned inmates to identify an available means for their own executions.”

The case also exposed deep disagreement among the justices on what type of access death-row prisoners should have to court review. In a non-binding portion of the lead opinion, Justice Gorsuch disparaged method-of-executions challenges in general as often being “tools to interpose unjustified delay” and urged that “[l]ast-minute stays should be the extreme exception, not the norm.” Justice Breyer responded that it is inappropriate to redress execution delays by “curtailing the constitutional guarantees afforded to prisoners” and that the delays necessary to ensure that capital punishment is fairly imposed and properly carried out may be evidence that “there simply is no constitutional way to implement the death penalty.” Justice Sotomayor criticized the majority’s comments about last-minute stays as “not only inessential but also wholly irrelevant to its resolution of any issue” before the Court. She cautioned that “[i]f a death sentence or the manner in which it is carried out violates the Constitution, that stain can never come out. Our jurisprudence must remain one of vigilance and care, not one of dismissiveness.”

The schism in the Court was evident as well in several other hotly contested applications for stays of execution. In Dunn v. Price, the Court overturned stays of execution ordered by an Alabama district court and the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. Christopher Price challenged Alabama’s lethal injection protocol and also suggested nitrogen hypoxia — which was authorized in the state’s execution statute — as an alternative execution method. In a post-midnight order vacating the stays, the majority rejected Price’s challenge as untimely, saying he had failed to select lethal gas during a 30-day window created when Alabama added lethal gas to its execution statute and then waited too long to challenge the state’s method of execution. Justice Breyer’s dissent expressed alarm about the majority’s insistence on vacating a stay after midnight despite Breyer’s request to consider the issue at a prescheduled conference to be attended by all the justices that morning. “To proceed in this way calls into question the basic principles of fairness that should underlie our criminal justice system,” Breyer wrote.

Two stay of execution applications brought religious rights issues to the fore. Domineque Ray and Patrick Murphy challenged state procedures that excluded their religious advisors from the execution chamber while allowing Christian religious advisors to be present. Ray was a Muslim challenging Alabama’s execution procedures, and Murphy is a Buddhist challenging Texas’ procedures. The Supreme Court vacated a stay of Ray’s execution in February, generating a fierce backlash across the political spectrum from those concerned with religious rights. One month later, the Court stayed Murphy’s execution, which presented apparently indistinguishable issues. The Court’s apparently inconsistent actions raised questions of religious discrimination and disparate treatment, and prompted an extraordinary set of explanatory opinions later in the term attempting to explain their decisions.

In its most substantive death-penalty decision of 2019, the Supreme Court found that a Mississippi district attorney had unconstitutional excluded African Americans from serving as jurors in Curtis Flowers’s case (Flowers v. Mississippi). District Attorney Doug Evans had prosecuted Flowers six times for a 1996 quadruple murder. Throughout these trials, Evans repeatedly attempted to strike as many African-American potential jurors as he could. The Court made clear that, under the Batson v. Kentucky doctrine prohibiting the race-based exclusion of jurors, this history was relevant in determining whether his jury strikes in the sixth trial were based on race. In an opinion by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the Court reversed the Mississippi Supreme Court and vacated Flowers’ conviction.

However, the Court refused to intervene in other death-penalty cases that presented significant evidence of racial discrimination (Tharpe v. Ford, Jones v. Oklahoma, Wood v. Oklahoma) and refused to hear a case (Rhines v. Young) presenting substantial evidence of anti-gay bias.

Two of the Court’s substantive decisions were second looks at cases that had previously been before the Court. In Madison v. Alabama, the Court clarified the constitutional standards governing challenges to a prisoner’s competency to be executed. Alabama planned to execute Vernon Madison, an aging prisoner who had suffered multiple severe strokes that caused brain damage, vascular dementia, and retrograde amnesia, also leaving him with slurred speech, legally blind, incontinent, and unable to walk independently. Alabama had argued that Madison was not incompetent because his cognitive impairments were not caused by psychosis. Justice Elena Kagan, writing for the Court, declared that competency determinations are governed by whether a prisoner has a rational understanding of what an execution is and why he is being executed, not by what physical or mental health condition impairs his understanding.

In Moore v. Texas, the Court reiterated that the determination of intellectual disability as a bar to execution must be based on clinical criteria, not lay stereotypes. The Court had previously reversed the Texas state and federal courts’ rejection of Bobby Moore’s intellectual disability claim, setting forth the appropriate standard for resolving the issue. Moore’s case returned to the Supreme Court after the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected a concession by county prosecutors that Moore was intellectually disabled and, for a second time, denied his intellectual disability claim. The Supreme Court again reversed and declared that Moore had proven his intellectual disability. In other intellectual disability cases, the Court remanded a Kentucky case for further consideration in light of the opinion (White v. Kentucky), but reversed a federal habeas decision that had applied the 2017 Moore opinion in determining whether a state court decision that predated Moore had unreasonably applied prior Supreme Court decisions (Shoop v. Hill).

Key Quotes Top

“How you going to stop your heart from hurting when it’s your baby that they about to put to sleep?” — Estelle Barrau, mother of Georgia death-row prisoner, Ray Cromartie

“Our death penalty system has been, by all measures, a failure. It has discriminated against defendants who are mentally ill, black and brown, or can’t afford expensive legal representation. It has provided no public safety benefit or value as a deterrent. It has wasted billions of taxpayer dollars. But most of all, the death penalty is absolute. It’s irreversible and irreparable in the event of human error.” – Governor Gavin Newsom, announcing moratorium

“I don’t believe in the death penalty. I feel like there are situations where an individual can be redeemed or be healed and mentally or physically with whatever the issue is and the root of why they are in that situation.” – Basketball star Steph Curry

“Ohio is not going to execute someone under my watch when a federal judge has found it to be cruel and unusual punishment.” – Ohio Governor Mike DeWine

“Yes, Daniel Lee damaged my life, but I can’t believe taking his life is going to change any of that. I can’t see how executing Daniel Lee will honor my daughter in any way. In fact, it’s kind of like it dirties her name, because she wouldn’t want it and I don’t want it. That’s not the way it should be. That’s not the God I serve.” – Earlene Branch Peterson, whose family was killed by Daniel Lee, requesting clemency

“The death penalty does not prevent violence. It does not solve crime. It does not provide services for families like ours. It does not help solve the over 250,000 homicide cold cases in the United States. It exacerbates the trauma of losing a loved one and creates yet another grieving family. It also wastes many millions of dollars that could be better invested in programs that actually reduce crime and violence and that address the needs of families like ours.” – 175 victims’ family members, in a letter to President Trump and Attorney General Barr

“I think people can learn forgiveness and love and make the world a better place. That’s all I have to say.” — Last words of Tennessee death-row prisoner Lee Hall before he was executed December 5, 2019

Downloadable Resources Top

Click HERE to download 2019 Execution Data as an Excel File

Click HERE to download 2019 Sentencing Data as an Excel File

Click image to download (PNG)