A recent study by Professor Steven Shatz of the University of San Francisco Law School and Naomi Shatz of the New York Civil Liberties Union suggests that gender bias continues to exist in the application of the death penalty, and that this bias has roots in the historic notion of chivalry. In a review of 1,300 murder cases in California between 2003 and 2005, the authors found gender disparities with respect to both defendants and victims in the underlying crime. The study revealed that the influence of gender-based values was particularly pronounced in certain crimes: gang murders (few death sentences), rape murders (many death sentences), and domestic violence murders (few death sentences). The authors concluded: “The present study confirms what earlier studies have shown: that the death penalty is imposed on women relatively infrequently and that it is disproportionately imposed for the killing of women. Thus, the death penalty in California appears to be applied in accordance with stereotypes about women’s innate abilities, their roles in society, and their capacity for violence. Far from being gender neutral, the California death penalty seems to allow prejudices and stereotypes about violence and gender, chivalric values, to determine who lives and who dies.”

The authors further concluded that “[b]ecause women are stereotyped as weak, passive, and in need of male protection, prosecutors and juries seem reluctant to impose the death penalty upon them.” On the other hand, in cases where the victim was a woman, the death sentence rate was 10.9%, seven times the rate when men were victims (1.5%).

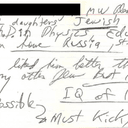

(S. Shatz and N. Shatz, “Chivalry is Not Dead: Murder, Gender, and the Death Penalty,” February 19, 2011). See Women and the Death Penalty.