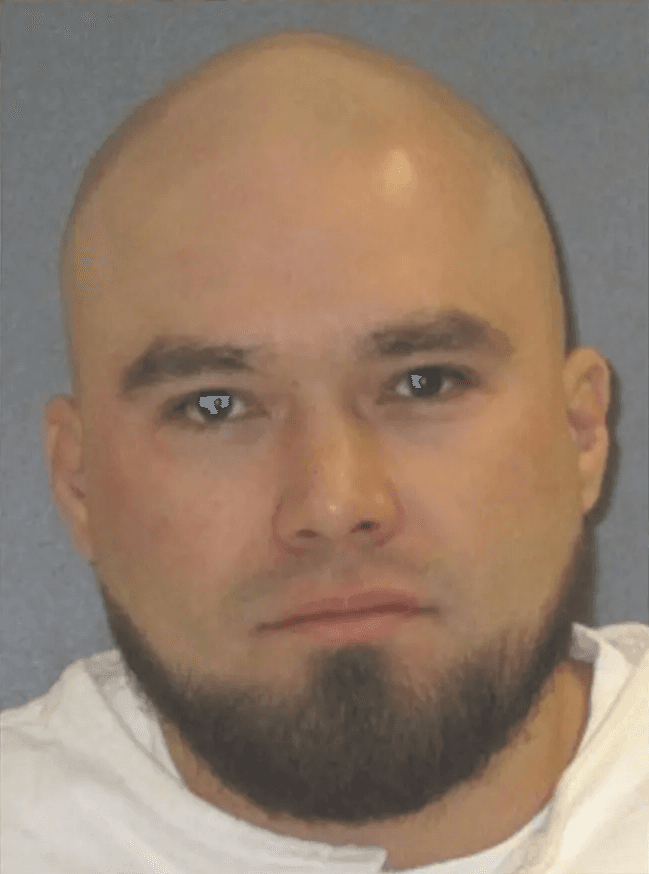

On March 24, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed lower court orders that had denied a Texas death-row prisoner’s request for his pastor to touch him and audibly pray during his execution. In ruling for John Henry Ramirez (pictured), the Court emphasized Texas’ ability to prevent any delay of his execution by simply creating reasonable procedures to allow Ramirez the accommodations he seeks. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the opinion of the court, joined by seven other Justices. Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter, characterizing Ramirez’s pursuit of post-conviction litigation as a “history of seeking unjustified delay.”

Prior to his September 8, 2021 execution date, Ramirez requested that his pastor “lay hands” on him and “pray over” him during his execution. When this request was denied by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Ramirez filed suit in federal court, arguing that Texas intended to violate his First Amendment right to free exercise of religion and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (“RLUIPA”). A Texas federal district court denied Ramirez’s request for a preliminary injunction, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed.

In an order released nearly three hours after Ramirez’s execution was scheduled to begin, the Supreme Court halted Texas’ planned execution of Ramirez and agreed to review his claim. It was the fourth time since 2019 that the Court had stayed an execution based on a dispute over the exercise of religion in the death chamber, but the first time it had scheduled any of those cases for full briefing and argument. The Court had not granted stays of execution for any other reasons during that time period.

At oral argument, the Justices appeared troubled by the implications of Texas’ policy on religious freedom but also concerned about “last-minute litigation” by death row prisoners.

In the Court’s opinion granting relief, it rejected Texas’ arguments that Ramirez had failed to exhaust available remedies and that the challenge did not arise from Ramirez’s sincere religious beliefs. The Court then considered whether Texas’ ban on audible prayer and touch in the execution chamber was the “least restrictive means of furthering [a] compelling government interest.” Citing an amicus curiae brief submitted by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, the Court recognized that “there is a rich history of clerical prayer at the time of a prisoner’s execution, dating back well before the founding of our Nation.” The Court also noted that until recently Texas had permitted audible prayer and physical touch in the execution chamber.

In light of this history, the Court found that Texas had provided weak arguments that a ban on audible prayer and touching was the least restrictive method to preserve the safety and solemnity of the execution chamber. The Court noted that through simple regulations communicated in advance of the execution, Texas could address its safety and security concerns. As a result, the majority concluded that Ramirez would likely prevail on the merits of his RLUIPA claim and that the other preliminary injunction factors justify relief.

Though joining the majority opinion, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Brett Kavanaugh wrote separate concurring opinions. Justice Sotomayor emphasized the responsibility of prison administrators to provide timely notice of execution procedures and to decide on execution-related requests in time for condemned prisoners to challenge such decisions. She noted that Ramirez had not been timely notified of Texas’ restrictions on spiritual advisors and that Texas took 39 days to resolve Ramirez’s initial grievance. Justice Sotomayor concluded that prisoners should not “be penalized for delays attributable to prison administrators.”

Justice Kavanaugh focused on the history of the Court’s handling of execution-related religious rights cases, the importance of considering jurisdictions’ prior practice in assessing Ramirez’s claim, and guidance for the states. He suggested that “to avoid persistent future litigation and the accompanying delays, it may behoove States to try to accommodate an inmate’s timely and reasonable requests about a religious advisor’s presence and activities in the execution room if the States can do so without meaningfully sacrificing their compelling interests in safety, security, and solemnity.”

Justice Clarence Thomas filed a lone dissent, stating his belief that Ramirez not only failed to satisfy his burden by failing to properly exhaust his administrative claims, but also only aimed to continue to delay his execution.

Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Rules for Condemned Inmate Who Sought Pastor’s Touch, The New York Times, March 24, 2022; Zoe Strozewski, Texas Inmate Can Have Pastor Pray, Touch Him During Execution: SCOTUS, Newsweek, March 24, 2022; Amy Howe, Court bars Texas from executing inmate unless it allows pastor’s touch and audible prayer, SCOTUSblog, March 24, 2022.

Read the Supreme Court’s decision here.