On February 28, 2025, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey commuted the death sentence of Robin ‘Rocky’ Dion Myers to Life Without Parole (LWOP). Myers was convicted in the 1991 murder of Ludie Mae Tucker in Decatur, Alabama. His jury recommended that he be sentenced to LWOP, but the judge in his case overrode the jury’s recommendation and handed down a death sentence. The practice of judicial override was abolished in Alabama in 2017. In her statement, Gov. Ivey repeated her belief that “the death penalty is just punishment for society’s most serious crimes” but she also noted that in Mr. Myer’s case, she had “enough questions about [his] guilt that I cannot move forward with executing him.”

In support of her decision, Gov. Ivey noted that no evidence directly linking Mr. Myers to the scene of the crime had been found, and that eyewitnesses to the crime never identified Mr. Myers as the assailant. While unconvinced of his innocence, Gov. Ivey said she was also not convinced of his guilt. A former juror in the case, Mae Puckett, came forward in 2023 with her belief that Mr. Myers was not guilty: “They never placed him in the house that night … I know he is innocent.” This was only the second grant of clemency in a death penalty case in Alabama in the modern death penalty era. The last time anyone was granted clemency in Alabama was in 1999.

“I am not convinced that Mr. Myers is innocent, but I am not so convinced of his guilt as to approve of his execution.”

“I’m not sure there are words enough to convey my joy, relief, and gratitude at learning of Gov. Ivey’s decision to commute Mr. Myers’ sentence[.]”

While Gov. Ivey was reluctant to declare Mr. Myers innocent, possible innocence plays a large role in many clemency decisions nationwide. A recent review by DPI of the public reasons given by those authorized to grant clemency found that possible innocence was cited in 26% of all individual clemency cases and was one of the top four reasons cited nationwide. Other frequently cited reasons for clemency include mitigating factors (cited in 31% of all cases), comparative culpability (which occurs when there are multiple defendants involved and yet only one is charged capitally: cited in 29% of all cases); and official misconduct or unfair legal practices (cited in 23% of all cases). NB: many cases cited more than one factor.

Less than one percent of those sentenced to death nationwide since Furman have received an individual grant of clemency, and less than half of one percent (2/479) of the individuals sentenced to death in Alabama have been granted clemency.

Grants of clemency are still relatively rare in the modern death penalty era, whose start is marked by the Supreme Court’s 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia. Only about four percent of those sentenced to death (366/8914) since Furman have had their sentences commuted. Half of those clemencies came from a single mass grant of clemency in Illinois in 2003, when outgoing Governor George Ryan commuted the sentences of all 167 people on the state’s death row and pardoned an additional four individuals. 2024 was the second-highest year on record for grants of clemency, with former President Biden commuting 37 federal death sentences and North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper commuting 15 sentences to LWOP. Individual commutations, like the one for Mr. Myers, are even rarer: less than one percent of those sentenced to death nationwide since Furman have received an individual grant of clemency, and less than half of one percent (2/479) of the individuals sentenced to death in Alabama have been granted clemency.

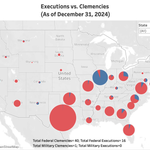

Grants of clemency relative to execution rates vary greatly from state to state. Because of the mass grant of clemency in Illinois in 2003, the number of individuals granted clemency far outstrips the number of executions in the state since 1972 (see map). In contrast, in Texas, the state with the most executions in the modern era, only 37 individuals, or just over half a percent (37/590), have had their sentences commuted.

Alabama’s last grant of clemency came in January 1999, when Alabama Governor Fob James, who had just been voted out of office, granted clemency to Judith Ann Neelley, who had been convicted in 1983 at age 18 of killing a 13-year-old. The jury in her case had recommended LWOP, but the judge handed down a death sentence. Ms.Neelley’s co-defendant in the case, her husband, whom she married at the age of 15 and who had physically and sexually abused her, was sentenced to LWOP in a plea deal. Ms. Neelley’s was the first commutation of a death sentence in Alabama in 45 years.

The lawyer representing Ms. Neelley at the time of her commutation said that Gov. James had conditioned consideration of her clemency petition on absolute secrecy — “No AG. No press. No one.” In an interview after the fact, Governor James cited the jury LWOP recommendation as his reason for granting the clemency. Given that the governor had excluded from his largess numerous men facing death under similar circumstances, her lawyer commented at the time that he believed “her gender saved her life.” Under the terms of her commutation, Ms. Neelley was made parole-eligible by Gov. James, but she is still incarcerated at this time. Alabama Gov. Ivey opposed parole for Ms. Neelley the last time the question arose in 2023. In the wake of Ms. Neelley’s case, the Alabama legislature amended the State’s clemency statute (Ala. Code § 15 – 22-27(b)) to prohibit the Governor’s office from commuting condemned individuals to a parole eligible sentence.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey commutes death sentence of Robin ‘Rocky’ Myers; Governor Commutes Sentence of Decatur Man Convicted of 1991 Murder; He is Innocent: Juror Urges Clemency for Alabama man Facing execution; DPI Podcast: He May Be Innocent and Intellectually Disabled, But Rocky Myers Faces Execution in Alabama; Governor Kay Ivey Strongly Opposes Parole of Convicted Child Murderer Judith Ann Neelley. The Neelley Commutation.