In a unanimous ruling, the California Supreme Court has limited the reach of a controversial voter initiative that was intended to accelerate judicial review of death-penalty cases. In In re: Friend, decided June 28, 2021, the court ruled that provisions of Proposition 66 that strictly limit a death-row prisoner’s ability to file successive challenges to his or her capital conviction or death sentence do not bar a capital petitioner from filing a second or subsequent petition that raises new claims that could not have been raised in the prisoner’s initial petition.

Death-penalty proponents, led by the arch conservative Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, had argued that the Death Penalty Reform and Savings Act of 2016, Prop 66’s formal name, barred death-row prisoners from filing any successive petition unless the prisoner established his or her actual innocence of the crime or ineligibility for the death penalty. They argued that the term “successive petition” should be interpreted literally to limit death-row prisoners to filing a single state habeas corpus petition, regardless of new facts or court decisions that might affect the outcome of their cases.

Lawyers for death-row prisoner Jack Wayne Friend, the petitioner in the case — joined by the California Attorney General’s office — argued that Proposition 66 did not change the established legal meaning of the term “successive petition,” which applied only to circumstances in which a petitioner attempted to relitigate a claim that had already been raised or untimely present a claim that could have been raised in a prior habeas petition. Under California law, they argued, a second or subsequent petition was not successive, and therefore could properly be filed, if the petitioner could not have been aware of the claim at the time the initial petition was filed. Applying a “successive petition” bar to such claims, Friend argued, raised significant constitutional concerns.

The Supreme Court of California agreed with Friend and the Attorney General’s office. The restrictions imposed in Proposition 66 regarding successive claims, the court said, “do not limit consideration of claims that could not have been raised earlier, such as those based on newly available evidence or on recent changes in the law.” Rather, the successor bar applies only to repetitive claims or when “the claim was omitted from an earlier petition without justification, and its presentation therefore constitutes abuse of the writ process.” A claim that was not presented earlier because of ineffective representation by a capital petitioner’s prior habeas counsel is also not a successive claim, the court said.

Proposition 66 enacted a series of changes in the law ostensibly intended to make the system of capital punishment “more efficient, less expensive, and more responsive to the rights of victims.” The changes included time limits on filing and adjudicating capital appeals, as well as limitations on the circumstances in which a death-row prisoner could file a habeas corpus petition in state court.

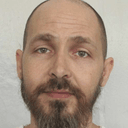

Friend was convicted and sentenced to death in the 1984 robbery and murder of an Oakland bartender. The California courts had affirmed his conviction and sentence on direct review and dismissed his state habeas corpus petition. In 2018, new lawyers representing Friend filed a second state habeas petition to raise six unaddressed claims. However, Proposition 66 became law before Friend filed his second state court petition. The Alameda County Superior Court applied the “successive petition” provisions of the new law to dismiss Friend’s petition. The California Supreme Court then agreed to review Friend’s case to resolve legal issues related to the prohibition on successive petitions.

The pro-death penalty Criminal Justice Legal Foundation filed an amicus brief in Friend’s case, arguing for strict limitations on a death-row prisoner’s access to judicial review. The Innocence Network also submitted an amicus brief, arguing that the state’s provision of counsel to represent death-row prisoners in their initial petitions did not justify restrictions on subsequent filings raising claims that counsel could not have been aware of or ineffectively failed to present.

The court’s decision was the second major limitation it has imposed on the reach of Proposition 66. In November 2016, California death penalty opponents filed a taxpayer suit to block the proposition from going into effect. The lawsuit was filed by former El Dorado County supervisor Ron Briggs —who co-authored the measure to reinstate California’s death penalty in 1978 — and former California Attorney General John van de Camp. Their lawsuit argued that the measures contained in the proposition would “impair the courts’ exercise of discretion, as well as the courts’ ability to act in fairness to the litigants before them” and raised concerns that in the rush to meet the appellate time limits, death-row prisoners would be assigned lawyers “who do not currently meet [California’s counsel] qualification standards.”

In 2017, in Briggs v. Brown, the California Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Proposition 66 but severely limited its scope. The majority ruled that the measure’s primary provision — a five-year deadline on appeals by condemned prisoners — was “directive, rather than mandatory”; that “courts must make individualized decisions based on the circumstances of each case”; and that “prisoners may seek to challenge [the time limitations and limitation on the claims they are permitted to raise] in the context of their individual cases.”

Staff, California Supreme Court: Proposition 66 Doesn’t Bar Showing of New Evidence, Metropolitan News-Enterprise, June 29, 2021.

Read the California Supreme Court’s opinion in In re: Friend.