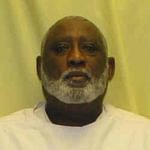

Seventy-nine-year-old James Frazier (pictured) is Ohio’s oldest death-row prisoner. He has dementia, he cannot walk, and he requires the assistance of aides to complete daily tasks. Because of his special medical needs, he is incarcerated at the Franklin Medical Center, rather than on Ohio’s death row at the Chillicothe Correctional Institution. Ohio is scheduled to execute him on October 20, 2021.

An April 19, 2020 story in the Cleveland Plain Dealer highlights Franklin’s case and the growing problems associated with the aging of the nation’s death row: how many prisoners are at risk of developing physical and mental health problems that impair their understanding that they are condemned to die and why? The lengthy appeals process — necessary to identify and redress constitutional defects common in death-penalty trials — has resulted in prisoners aging in solitary confinement on death row and facing the physical and mental decline that can come from the combination of old age, oppressive physical conditions, and the extreme stress of facing execution.

About one-quarter of the nation’s 2,620 death-row prisoners are age 60 or older, the same proportion as in Ohio. And death row is growing older with more and more prisoners developing dementia and other mental disorders that threaten their competency and may render attempts to carry out their executions cruel and unusual punishment.

According to Bureau of Justice Statistics data, 39 prisoners aged 60 and older were on death rows across the United States in the mid-1990s, a figure that had risen to 110 by the end of 2003. Between 2007 and 2013, the percentage of death-row prisoners who were 60 or older more than doubled, increasing from 5.8% to 12.2%. It has doubled again in the six years since then.

Frazier’s attorneys argue that his execution “would constitute cruel and unusual punishment because he lacks a rational understanding of the state’s rationale for his execution.” Dr. Joette James, a neuropsychologist who has examined Frazier since 2016, said his cognitive abilities have declined even further over the last three years. His speech and thought processes, she wrote in a report, are “rambling, disorganized and incoherent.” He failed cognitive tests such as counting backwards from 20 and naming the months of the year in reverse order. His attorneys believe he may have had a stroke before he was moved to the prison medical facility in 2018.

Assuming Frazier lives to his scheduled execution date, the outcome of his case may depend on the U.S. Supreme Court’s February 2019 decision in Madison v. Alabama. Vernon Madison was an Alabama death-row prisoner whose severe dementia from a series of strokes left him with no memory of the crime for which he was sentenced to death and compromised his understanding of why he was to be executed. In Madison’s case, the Court ruled that its earlier decision barring the execution of prisoners who lacked “a rational understanding of the reason for [their] execution” was not limited to cases of psychotic mental illness, but applied equally to those whose understanding was compromised by dementia. Madison died on death row in February 2020 at the age of 69, before a state court hearing could be held to determine his competency to be executed.

“One of the side effects of our death-penalty system is that it takes a long time,” said capital appeals defense lawyer Michael Benza, a Case Western Reserve University senior instructor in law. “We’re going to see more and more people like Vernon Madison and James Frazier, and we won’t be able to carry out their executions.” Angie Setzer, a lawyer for the Equal Justice Initiative that represented Madison, said, “What is the punitive value of executing someone like Mr. Madison, whose cognitive decline prevents him from understanding what is happening to him and why?”

If Frazier is executed, he would be the second-oldest person executed in the U.S. In 2018, Alabama executed 83-year-old Walter Moody. Ohio has not carried out an execution since July 2018. All executions since that time have been rescheduled due to problems with the state’s lethal-injection protocol and the unavailability of lethal-injection drugs. In November 2017, the state botched the attempted execution of 69-year-old terminally ill death-row prisoner Alva Campbell (pictured, left), whose debilitated physical condition prevented executioners from finding a usable vein to set the execution IV line. Campbell’s execution was rescheduled for June 2019, but he died of his illnesses in March 2018.

John Caniglia, Growing old on death row: Age-related health concerns could impact executions in Ohio, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 19, 2020.

Ohio

Jan 31, 2024