DPIC MID-YEAR REVIEW: Pandemic and Continuing Historic Decline Produce Record-Low Death Penalty Use in First Half of 2020

- Introduction

- First-Half 2020 Death Sentences

- First-Half 2020 Executions

- First-Half 2020 Exonerations

- State Milestones

- Public Opinion

Introduction Top

The combination of the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and the continuing broad national decline in the use of capital punishment produced historically low numbers of new death sentences and executions in the first half of 2020.

Even before the pandemic, the U.S. was poised for its sixth consecutive year with 50 or fewer new death sentences and 30 or fewer executions. At the midpoint of 2020, there had been 13 new death sentences, imposed in seven states, and six executions carried out by five historically high-execution states. Florida (4), California (3), and Texas had imposed multiple new death sentences, but only Texas (with 2) had carried out more than one execution.

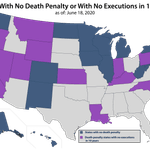

Colorado became the 22nd U.S. state to abolish the death penalty, and Governor Jared Polis commuted the death-sentences of the three prisoners remaining on the state’s death row. Louisiana and Utah joined the list of twelve death-penalty states that have not carried out an execution for more than a decade. Two more death-row prisoners were exonerated, and courts issued orders setting the stage for another, bringing to 169 the number of people in the U.S. exonerated from wrongful convictions and death sentences since 1973.

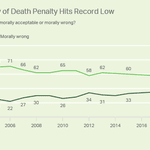

As the U.S. Supreme Court refused to intercede in the federal government’s second attempt to resume federal executions, public support for the death penalty continued to decline. A May 2020 national Gallup poll found a record-low percentage of U.S. adults now believe that the death penalty is a morally acceptable punishment.

State courts continued to have a major impact on the course of capital punishment. In a decision with ramifications for more than 140 death penalty cases, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down a legislative attempt to retroactively repeal the state’s Racial Justice Act. At the same time, new appointees to the Florida Supreme Court overturned established procedural safeguards in three death penalty cases, including abandoning case precedent that required a unanimous jury recommendation for death before a trial judge could impose the death penalty. The court’s decision in State v. Poole could retroactively reimpose dozens of death sentences that previously had been overturned.

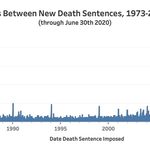

First-Half 2020 Death Sentences Top

2016 through 2019 produced four of the five lowest death-sentencing years in the U.S. since the Supreme Court struck down existing death-penalty statutes in Furman v. Georgia in 1972. With new death sentences already near historic lows and most capital trials and sentencings now suspended or delayed, 2020 is expected to produce the fewest death sentences of any year in the modern history of the U.S. death penalty.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, relatively few capital trials were underway across the country. Since the pandemic struck, defense teams have been unable to safely and meaningfully investigate and prepare their cases, and the potentially life-threatening risks to witnesses, jurors, defense and prosecution lawyers and investigators, court personnel, and their families and communities have led to the suspension or postponement of most capital trials:

- In Florida, the trial of accused Parkland school shooter Nikolas Cruz has been postponed indefinitely.

- An Ohio court suspended the death-penalty trial of Stanley Ford, charged with arson and murder in fires that killed nine people, including five children, then declared a mistrial two months later when jurors objected to returning for an expected three to four weeks of additional testimony.

- A Kentucky judge pushed back the start of the high-profile trial of Justin Smith, accused of the 2015 murder of a University of Kentucky student, until at least May 2021.

- After heavy criticism for continuing to pursue capital charges against Marco Garcia-Bravo even after the Colorado legislature had prospectively abolished the death penalty, prosecutors eventually dropped the death penalty in April following the postponement of jury selection until at least July 17.

- In Nebraska, the penalty-phase hearing in the capital prosecution of Aubrey Trail, originally scheduled before a three-judge panel for June 23 – 26, was delayed until December 15.

Only two death sentences have been imposed since the pandemic began shutting down courts in mid-March. Neither of those sentences — a trial before a three-judge panel in Ohio and a California trial court’s acceptance of a jury verdict issued in January — involved new jury action, nor did the last sentences imposed prior to the pandemic.

The last death sentences imposed before the widespread court closures were handed down by a Florida trial judge on March 13, who sentenced Jesse Bell and Barry Noetzel to death after they pled guilty and were permitted to waive their rights to counsel and a jury sentencing. The next new death sentence came on May 18, when an Ohio three-judge panel sentenced Joel Drain to death. Drain had waived his right to a jury trial and sentence, presented no guilt defense and refused to present mitigating evidence in the penalty-phase of his trial. The 66 days between those two death sentences was the longest the United States had gone without a new death sentence since 1973.

The few death sentences imposed in the first half of 2020 add fuel to long-standing criticisms of the arbitrariness and unreliability of death-penalty proceedings and whose lives matter most in the administration of U.S. criminal laws. In nearly one-third of the cases (4 of 13), defendants had waived their rights to legal representation, and/or their rights to jury trial or sentencing, continuing a disturbing pattern of death sentences resulting from the worst of the worst legal process.

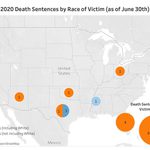

Race remained an issue. Eight of the new death sentences were in cases involved only white victims; none involved only Black victims. Seven death sentences were imposed for killing a single white victim and another was imposed for the murder of one Latina victim. No death sentences were imposed for a single-victim killing of a Black victim. The two death sentences imposed for interracial killings involved Black defendants.

“Golden State Killer” Joseph DeAngelo, Jr. pleaded guilty to 13 murders and admitted to dozens of rapes and more than 150 crimes involving 48 victims in exchange for 11 life sentences. The plea deal spared DeAngelo the death penalty, one year after California prosecutors had called a press conference using his case to blast Governor Gavin Newsom’s declaration of a moratorium on executions as a “slap in the face” of murder victims’ families. The deal raised recurring questions of the arbitrariness and lack of proportionality in capital charging and sentencing.

First-Half 2020 Executions Top

Midway through 2020, it appears that U.S. states are likely to carry out fewer executions than in any year since 1991, when there were 14 executions. Of the 54 executions dates set for 2020, six executions have been carried out, with nine scheduled executions still pending. The few jurisdictions that are attempting to carry out executions are outliers in both their criminal justice and public health policies, prioritizing immediately executing prisoners over public health and safety concerns and fair judicial process. Eight executions have been stayed or rescheduled as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The year’s executions also have highlighted continuing trouble spots in the U.S. death penalty. All six men executed this year had mental illness (2), low IQ or brain damage (3), and/or severe childhood trauma or abuse (4). The six cases that resulted in executions so far this year have also featured systemic flaws, including ineffective representation, denial of DNA testing, curtailed legal process, opposition by victims’ families, and claims of innocence.

- John Gardner was executed in Texas after the Supreme Court refused to hear a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

- Donnie Lance was executed in Georgia over the clemency pleas of the children he and the victim shared. Lance maintained his innocence in the murder of his ex-wife and her boyfriend, but he was the third consecutive Georgia prisoner to be executed after being denied potentially exculpatory DNA testing.

- Abel Ochoa was executed in Texas after unsuccessfully seeking a stay of execution alleging that Texas unconstitutionally interfered in the clemency proceedings in his case by preventing him from submitting evidence in support of his clemency application.

- Nicholas Sutton was executed in Tennessee. His clemency petition was supported by members of the victims’ families, five jurors who sentenced him to death, and multiple corrections officers who not only testified to Sutton’s rehabilitation, but shared stories of incidents in which he had put himself in danger to save their lives.

- Nathaniel Woods was executed in Alabama despite prosecutors’ acknowledgement that his co-defendant was the shooter in the underlying crime. His conviction was tainted by allegations of racism, police corruption, intimidation of witnesses, and inadequate representation. He was sentenced to death by a non-unanimous jury.

- Walter Barton was executed in Missouri, becoming the first person executed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Barton’s defense team obtained affidavits from three jurors that “compelling” new expert analysis contradicting the junk science used to convict Barton would have made them reconsider their votes at his trial.

First-Half 2020 Exonerations Top

Two more innocent men who were wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death – Paul Browning and Walter Ogrod – were exonerated, the nation’s 168th and 169th death-row exonerations since 1973. Both exonerations occurred more than two decades after the wrongful convictions. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court also put in motion the July 1, 2020 exoneration of Pennsylvania death-row prisoner Kareem Johnson when it ruled on May 19 that his reprosecution would violate the state’s double jeopardy protections.

Paul Browning

Paul Browning was convicted and sentenced to death in 1986 for the robbery and murder of a Las Vegas jeweler. Browning was represented at trial by a lawyer who had been practicing criminal defense for less than a year and failed to interview the police who responded to the scene, examine the evidence against Browning, or investigate the crime. In his post-conviction appeal, Browning presented evidence that police and prosecutors had withheld evidence of a bloody footprint found at the scene that did not match Browning’s shoes or foot size, misrepresented blood evidence in the case, manipulated eyewitness testimony, failed to disclose benefits it offered to a key witness who may have committed the murder and framed Browning, and that the stab wounds suffered by the victim were inconsistent with wounds that would have been produced by the knife prosecutors claimed Browning had used to commit the killing. Browning also argued that a minimally competent defense investigation would have revealed the flaws in the prosecution’s evidence and the falsity of the representations the prosecution had made to the jury. A white witness who worked near the crime scene told police she had seen a man run by after the murder and thought it could have been Browning, but when police asked if she could be “more sure” about whom she had seen, she said, “No, I wouldn’t think so. No … They all look the same, and that’s just what I think when I see a black person, that they all look the same.” At trial, though, she unhesitatingly testified that Browning was the man she had seen.

In 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit overturned Browning’s conviction. Then, in March 2019, Clark County District Judge Douglas Herndon dismissed the charges against him, saying the deaths of key witnesses made it impossible for him to receive a fair trial. The Nevada Supreme Court affirmed Judge Herndon’s decision on January 24, 2020.

Walter Ogrod

Twenty-eight years after Philadelphia prosecutors first sought to take his life for the murder of four-year-old Barbara Jean Horn, Walter Ogrod was exonerated from Pennsylvania’s death row. Ogrod has consistently maintained his innocence in the 1988 murder of four-year-old Barbara Jean Horn. His first trial ended in a mistrial when one of the 12 jurors who had voted to acquit changed his mind. Before his second trial, prosecutors engaged the assistance of John Hall, a notorious jailhouse informant whom they nicknamed “the Monsignor,” who worked with another informant to fabricate a confession from Ogrod. That testimony, along with a false confession elicited after 14 hours of interrogation by homicide detectives who had coerced false confessions in several other cases, sent Ogrod to death row.

At the June 5 hearing, Philadelphia Assistant District Attorney Carrie Wood offered an emotional apology for the mishandling of the case. “First, I must turn to Mr. Ogrod and his family and friends,” Wood said. “I am sorry it took 28 years for us to listen to what Barbara Jean was trying to tell us…. That you are innocent… And that we not only stole 28 years of your life, but that we threatened to execute you based on falsehoods.”

She then addressed Horn’s mother, saying, “This office has not told you the truth about what happened to your little girl so many years ago. The truth is painful, and terrible, but it is what you deserved to hear from this office. And we did not do that. And I am so sorry. One of the most difficult things for me is not being able to tell you who did this to Barbara Jean. I can’t imagine the pain of thinking a chapter of your life has been closed only for it to reopen with unanswered questions.”

Finally, Wood apologized to the people of Philadelphia. “The errors made in this case made the streets less safe and I fear that the true perpetrator in this case, having been left on the streets, may have brought harm to others,” she said. “That is the impact of … wrongful convictions on our community. And for that, this office must apologize. And we must do better.”

State Milestones Top

Colorado became the 22nd U.S. state to abolish the death penalty. Two states – Louisiana and Utah – reached ten years with no executions. With those three events, 34 states – more than two thirds of the nation – have either abolished the death penalty or not performed an execution in at least a decade.

Public Opinion Top

Public opinion polls in the first half of 2020 documented continued declining support for capital punishment. According to the 2020 Gallup Values and Beliefs poll, released on June 23, 2020, 54% of U.S. adults — a record low — now say the death penalty is morally acceptable. That number, the lowest in the 20-year history of the poll, reflects a six-percentage-point decline over the course of the last year and is 17 percentage points below the 71% of respondents in 2006 who said that the death penalty was morally acceptable. A record-high 40% of Americans told Gallup they believe the death penalty is morally wrong.

The 2020 Houston Area Survey by Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research found that death-penalty support has declined by more than half since the turn of the 21st century in the city. The survey, released on May 4, 2020, reported that a record-low 20% of Houstonians now support the death penalty over life-sentencing alternatives. Houston comprises 50% of the population of Harris County, Texas, which has carried out more than twice as many executions in the past half century as any other county in the United States.

[UPDATED July 6, 2020 to include an additional new death sentence that had been imposed in Texas and a reference to the formal exoneration of Kareem Johnson in Pennsylvania on July 1.]