The Death Penalty in 2022: Year End Report

Public Support for Death Penalty at Near-Record Low Despite Perception that Violent Crime is Up

Unaccountability Highlights a Year of Botched Executions

Oregon’s Governor Commutes Death Row

Posted on Dec 16, 2022

- Introduction

- Significant Developments in 2022

- Execution and Sentencing Trends

- Innocence and Clemency

- Problematic Executions

- Public Opinion and Elections

- Problems with New Death Sentences

- Supreme Court

- Key Quotes

- Downloadable Resources

- Credits

Key Findings

- Eighth consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions and 50 new death sentences

- Botched executions and protocol errors lead to halts in Alabama and Tennessee

- Executions heavily concentrated in few jurisdictions – more than half in Oklahoma and Texas

Note: In March 2023, DPIC learned of one additional death sentence that was imposed in 2022: Leo Boatman, a white male defendant, was sentenced to death on November 9, 2022 in Bradford County, Florida, for the murder of Billy Chapman, a white male. Boatman’s death sentence brings the total to 21. The text below does not reflect that death sentence.

Introduction Top

In a year awash with incendiary political advertising that drove the public’s perception of rising crime to record highs, public support for capital punishment and jury verdicts for death remained near fifty-year lows. Defying conventional political wisdom, nearly every measure of change — from new death sentences imposed and executions conducted to public opinion polls and election results — pointed to the continuing durability of the more than 20-year sustained decline of the death penalty in the United States.

The Gallup crime survey, administered in the midst of the midterm elections while the capital trial for the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida was underway, found that support for capital punishment remained within one percentage point of the half-century lows recorded in 2020 and 2021. The 20 new death sentences imposed in 2022 are fewer than in any year before the pandemic, and just 2 higher than the record lows of the prior two years. With the exception of the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, the 18 executions in 2022 are the fewest since 1991.

One by one, states continued their movement away from the death penalty. On December 13, 2022, Oregon Governor Kate Brown announced the commutation of the capital sentences of all 17 death-row prisoners and instructed corrections officials to begin dismantling the state’s execution chamber. The commutations completed what she called the “near abolition” of the death penalty by the state legislature in 2019. Thirty-seven states — nearly three-quarters of the country — have now abolished the death penalty or not carried out an execution in more than a decade.

Death Row Population By State†

| State | 2022 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| California | 690 | 699 |

| Florida | 323 | 338 |

| Texas | 199 | 198 |

| Alabama | 166 | 171 |

| North Carolina | 138 | 139 |

| Ohio | 134 | 136 |

| Pennsylvania | 128 | 130 |

| Arizona | 116 | 118 |

| Nevada | 65 | 66 |

| Louisiana | 62 | 65 |

| Tennessee | 47 | 49 |

| U.S. Fed. Gov’t. | 44 | 46 |

| Oklahoma | 42 | 43 |

| Georgia | 41 | 45 |

| Mississippi | 37 | 40 |

| South Carolina | 37 | 39 |

| Arkansas | 29 | 31 |

| Kentucky | 27 | 27 |

| Oregon~ | 21 | 24 |

| Missouri | 20 | 21 |

| Nebraska | 12 | 12 |

| Kansas | 9 | 9 |

| Indiana | 8 | 8 |

| Idaho | 8 | 8 |

| Utah | 7 | 7 |

| U.S. Military | 4 | 4 |

| Montana | 2 | 2 |

| New Hampshire^^ | 1 | 1 |

| South Dakota | 1 | 1 |

| Virginia^ | 2 | |

| Wyoming | 1 | |

| Total | 2414‡ | 2474‡ |

† Data from NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund for April 1 of the year shown.

^Virginia abolished the death penalty with an effective date of July 1, 2021. The bill reduced the state’s two death sentences to life without parole.

^^ New Hampshire prospectively abolished the death penalty May 30, 2019.

‡ Persons with death sentences in multiple states are only included once in the total.

~Oregon Governor Kate Brown commuted all of the state’s death sentences on December 13. This shows Oregon’s death row population as of April 1.

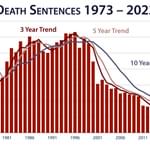

For the eighth consecutive year, fewer than 30 people were executed and fewer than 50 people were sentenced to death. The five-year average of new death sentences, 26.6 per year, is the lowest in 50 years. The five-year average of executions, 18.6 per year, is the lowest in more than 30 years, a 74% decline over the course of one decade. Death row declined in size for the 21st consecutive year, even before Governor Brown commuted the sentences of the 17 prisoners on Oregon’s death row.

2022 could be called “the year of the botched execution” because of the high number of states with failed or bungled executions. Seven of the 20 execution attempts were visibly problematic — an astonishing 35% — as a result of executioner incompetence, failures to follow protocols, or defects in the protocols themselves. On July 28, 2022, executioners in Alabama took three hours to set an IV line before putting Joe James Jr. to death, the longest botched lethal injection execution in U.S. history. Executions were put on hold in Alabama, Tennessee, Idaho, and South Carolina when the states were unable to follow execution protocols. Idaho scheduled an execution without the drugs to carry it out. One execution did not occur in Oklahoma because the state did not have custody of the prisoner and had not made arrangements for his transfer before scheduling him to be put to death.

Although states persisted in veiling the execution process in secrecy, what reporters were able to see, and what autopsies or failed executions revealed, was shocking. Witnesses reported significant problems in all three of Arizona’s executions, including the “surreal” spectacle of a possibly innocent man assisting his executioners in finding a vein in which to inject the lethal chemicals. An independent autopsy of Alabama prisoner Joe James Jr.‘s body revealed what a reporter who observed those proceedings described as “carnage.” The next two executions were called off while in progress because of the execution teams inability to set an IV line. Alabama Governor Kay Ivey called for a pause in future executions and ordered an internal “top-to-bottom review” of the state’s execution process.

Tennessee Governor Bill Lee stayed the execution of Oscar Smith when, shortly before it was set to occur, he learned that the execution team had failed to test the chemicals for impurities and contamination. Citing an “oversight” in execution preparations, he canceled all pending executions and commissioned a former federal prosecutor to undertake an independent review of the process.

South Carolina attempted to schedule two executions without having a complete execution protocol in place. Under state law, if lethal injection is unavailable, prisoners are forced to choose between electrocution or firing squad, but the state had no plan for firing squad executions. The state supreme court halted later scheduled executions to allow a trial court to adjudicate a challenge to the constitutionality of those methods. After a trial on the issue, the court ruled that they violated South Carolina’s constitutional prohibition against “cruel, unusual, and corporal punishments.”

A small number of jurisdictions that have historically been the heaviest users of capital punishment carried out a majority of executions and imposed most death sentences. Executions were concentrated in a handful of states – Oklahoma, Texas, Alabama, and Arizona – that have historically been among the most prolific executioners. But in most states and counties, cultural and political trends toward criminal legal reform and racial justice kept the death penalty out of favor, even as media and politicians escalated fears of crime. In the midst of political rhetoric reminiscent of the peak death penalty years of the 1990s, voters selected governors in the three states with moratoria on executions. Candidates who said they would not sign death warrants won in all three. Reform prosecutors were elected or re-elected across the country: in Dallas and San Antonio, Texas; Shelby County, Tennessee; Oklahoma County, Oklahoma; and Alameda County, California; among others.

The 18 executions carried out this year raised serious concerns about the application of the death penalty and the methods used to carry it out. Among those executed this year were prisoners with serious mental illness, brain damage, intellectual disability, and strong claims of innocence. In most jurisdictions, these cases would not even be capitally prosecuted today. Two prisoners were executed over the objections of the victims’ families, and two others were executed despite requests from prosecutors to withdraw their death warrants.

The arbitrariness of capital punishment was evident in sentencing decisions. Twenty people were sentenced to death in twelve states. Among those sentenced to death were at least four with significant trauma, one with brain damage, one who waived his right to counsel, and one who waived jury sentencing and asked for a death sentence. At the same time, several highly aggravated murder cases resulted in life sentences, including the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida and a high-profile quadruple-murder in Ohio. The juxtaposition of those cases that resulted in death sentences and those that resulted in life without parole belies the myth that the death penalty is reserved for the “worst of the worst.”

Innocence cases attracted national attention and support from unlikely actors. A bipartisan group of Oklahoma legislators released the findings of an independent investigation into the case of Richard Glossip. Representative Kevin McDugle, a Republican and self-described supporter of capital punishment, was so convinced by the evidence of Glossip’s innocence that he vowed, “If we put Richard Glossip to death I will fight in this state to abolish the death penalty simply because the process is not pure. I do believe in the death penalty, I believe it needs to be there, but the process to take someone to death has to be of the highest integrity.” The Texas case of Melissa Lucio similarly brought together a bipartisan group of legislators in support of clemency. Both Glossip and Lucio remain on death row; Glossip’s execution was delayed until 2023 by Governor Kevin Stitt, while Lucio’s was delayed indefinitely by a ruling from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

Two people – Samuel Randolph IV in Pennsylvania and Marilyn Mulero in Illinois – were exonerated, and DPIC’s research found two additional older exonerations, bringing the total to 190 people exonerated from death row since 1973. DPIC released its Death Penalty Census, which analyzed the status of more than 9,700 death sentences imposed from 1972 to January 1, 2021. The data reveal that the single most likely outcome of a death sentence imposed in the United States is that the sentence or conviction is ultimately overturned and not re-imposed. Nearly half of the sentences (49.9%) were reversed as a result of court decisions. By comparison, fewer than one in six (15.7%) death sentences ended in execution. DPIC’s ongoing prosecutorial accountability project identified more than 550 trials in which capital convictions or death sentences were overturned or wrongfully convicted death-row prisoners exonerated as a result of prosecutorial misconduct — more than 5.6% of all death sentences imposed in the past fifty years.

As the United States marked 50 years of the modern death penalty system, the arbitrariness and unreliability that led the Furman court to strike down capital punishment persist. As the systemic flaws of the death penalty have become clearer and more pronounced, it is being regularly employed by just a handful of outlier jurisdictions that pursue death sentences and executions with little regard for human rights concerns, transparency, fairness, or even their own ability to successfully carry it out.

Significant Developments in 2022 Top

Key Findings

- Oregon governor commutes its entire death row

- Oklahoma schedules 25 executions over a 29-month period, seeking to put to death 58% of its death row

- Kentucky becomes second state to pass serious mental illness exemption

- Three states – Idaho, Florida, and Mississippi – expand secrecy surrounding executions

Death penalty developments reflected the split between the growing number of states that have abandoned the use of capital punishment in law or practice and the extreme conduct of a small number of outlier states and counties that are attempting to carry out executions. At both the state and federal level, legislators grappled with the racial injustice in the criminal legal system. Two states took action to address questions of mental health and the death penalty. Meanwhile, three states took action to avoid public oversight of executions, and a fourth undertook an unprecedented spree of executions.

Legislation

Reform legislation passed on the state and federal level, while three states passed laws intended to expand execution secrecy and reduce public oversight of the execution process.

The California legislature and U.S. Congress took action to redress racism in the legal system. A federal law, first proposed nearly a century ago, made lynching a federal crime. At the signing ceremony, President Biden drew a historical link between the murder of Emmett Till, for whom the bill was named, and the 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery. “Racial hate isn’t an old problem; it’s a persistent problem,” Biden said.

California enacted the Racial Justice Act for All, a measure that retroactively applied the state’s 2020 Racial Justice Act to prisoners already sentenced to death and others convicted of felonies. Effective January 1, 2023, the expanded law permits death-row prisoners to challenge convictions obtained or sentences imposed “on the basis of race, ethnicity, or national origin.”

President Biden signing the Emmett Till Antilynching Act

Kentucky became the second state to pass a serious mental illness exemption, barring the death penalty for people diagnosed as seriously mentally ill. Kentucky provides for a narrow exemption, requiring that a defendant had a documented diagnosis and active symptoms of mental illness at the time of his or her offense. Ohio passed a somewhat broader serious mental illness exemption in 2021. On January 31, 2022, David Sneed — who faced an April 2023 execution date — became the third person removed from death row under the statute.

Voters in Alabama overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment to require the governor to provide advance notice to the attorney general and the victim’s family before granting a reprieve or commutation to any person sentenced to death. The amendment, which had no organized opposition, is expected to have little practical impact: Alabama governors have commuted only one death sentence in the past fifty years, and none since 1999.

Idaho, Florida, and Mississippi each passed laws designed to make it easier for the states to perform executions by reducing transparency in the execution process. New laws in Idaho and Florida will conceal from the public the identity of producers and suppliers of execution drugs. In both states, proponents of the bills claimed, without evidence, that the measures were necessary to protect drug suppliers from intimidation or harassment. Similar unfounded claims have been made in other states to justify secrecy policies.

Senator Todd Lakey

Idaho’s bill initially failed on a tie vote in committee. Historically, that had meant that that a bill was off the table for the remainder of the legislative session. But in a controversial parliamentary decision that deviated from past legislative practice, committee chairman Sen. Todd Lakey ruled that a tie vote is a “nullity” that “decides nothing” and allowed the committee to reconsider the bill. In the first test of source secrecy after the passage of the bill, the Idaho Department of Corrections called off the scheduled December 15, 2022 execution of Gerald Pizzuto, Jr. saying it was unable to find any source willing to sell it execution drugs.

Mississippi implemented a law giving unprecedented discretion to the Commissioner of Corrections in determining the method of execution. Prior to July 1, 2022, the state gave prisoners a choice of lethal injection, electrocution, firing squad, or nitrogen hypoxia. Under the new law, the Commissioner must notify a prisoner of which method will be used within seven days of an execution warrant being issued. There is no provision for transparency regarding the Commissioner’s selection of the method, and the law provides no guidance on how the method should be selected.

Legislators in fifteen states and U.S. Congress introduced bills to abolish the death penalty. Repeal bills received serious consideration in two states: Utah and Ohio. In Utah, an abolition bill sponsored by two Republican lawmakers failed in committee on a 6 – 5 vote. After the vote, bill sponsor Rep. V. Lowry Snow said, “This is not a matter of if, it is when the time is right, Utah will move forward.” A bipartisan repeal bill in Ohio is still pending, after four hearings were held in 2021.

Other State Developments

Outgoing Oregon Governor Kate Brown announced on December 13 the commutation of the death sentences of all 17 people on Oregon’s death row. Governor Brown commuted the death sentences to sentences of life without parole and ordered the dismantling of the state’s execution chamber.

Challenges to methods of execution remained at the forefront of death penalty litigation and controversy.

In South Carolina, the executions of Brad Sigmon and Richard Moore were halted in April to allow for a legal challenge to the state’s execution protocols. The state had first set executions for the men by lethal injection without having a supply of drugs to carry them out, then scheduled executions by electric chair without complying with a state-law requirement that they be provided the option to die by firing squad. In Moore’s legal filing, he said, “I believe this election is forcing me to choose between two unconstitutional methods of execution.” In September, a South Carolina trial court issued an injunction against executions by firing squad or electric chair after hearing four days of expert testimony. Judge Jocelyn Newman found that the methods violated the state constitution’s prohibition on “cruel, unusual, and corporal punishments.” The South Carolina Supreme Court is scheduled to hear the appeal in the case January 5, 2023.

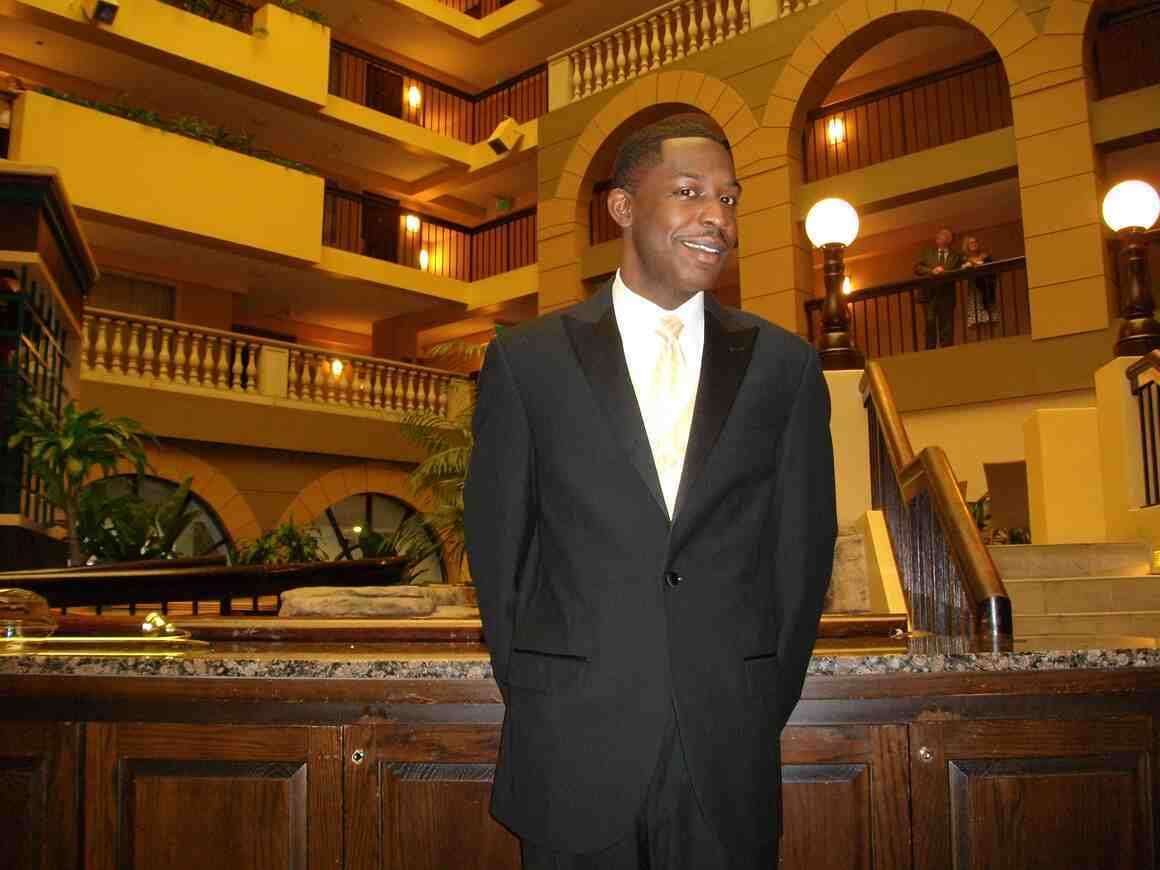

Oscar Smith

Governors in two southern states put executions on hold after serious problems in carrying out their lethal-injection protocols. Tennessee Governor Bill Lee announced on May 2 that he was pausing all executions scheduled for 2022 and ordering an “independent review” of the state’s execution protocol to address a “technical oversight” that led him to halt Oscar Smith’s execution less than a half-hour before it was scheduled to be carried out on April 21, 2022. In a series of articles published later in May, The Tennessean revealed mistakes and questionable conduct at every step of the lethal-injection process, from the compounding of the execution drugs by a pharmacy with a problematic safety history, to testing procedures, to the storage and handling of the drugs once they were in the possession of the Tennessee Department of Correction (TDOC).

In November, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey also halted executions indefinitely after the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) botched three consecutive executions. ADOC personnel struggled for three hours behind a closed curtain to establish an IV line to execute Joe James Jr., in the longest botched lethal-injection execution in U.S. history. ADOC called off the executions of Alan Miller and Kenneth Smith when it became clear that the execution team would not be able to set an intravenous execution line before the warrant expired. Ivey called for a “top-to-bottom review” of the execution process, but unlike Tennessee’s independent investigation, Ivey directed the Department of Corrections to investigate its own mistakes.

Florida became the seventh state since 2017 to address the conditions of confinement on death row. The state ended its practice of automatically incarcerating all death-sentenced prisoners in permanent solitary confinement. The Florida Department of Corrections agreed to the action as part of a settlement of a federal civil rights lawsuit brought by eight prisoners who alleged that the state’s death-row conditions were “extreme, debilitating, and inhumane, violate[d] contemporary standards of decency, and pose[d] an unreasonable risk of serious harm to the health and safety.” Five other states ended automatic prolonged solitary confinement for their death rows: Arizona, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia (which subsequently abolished its death penalty). A sixth state, Oklahoma, has not ended its practice of keeping death-row prisoners in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day, but has implemented some other changes, including eliminating incarceration in windowless cells, permitting contact visitation, and providing some opportunity for outside recreation.

Denials of Meaningful Process

Judge Stephen Friot

Throughout 2022, the few states that carried out executions exhibited a callous disregard for fair process and public or judicial oversight of their actions. The most notable example was Oklahoma, which scheduled 25 executions over the course of 29 months. The state court’s execution orders came two weeks after the prisoners filed notice in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit that they intended to appeal federal district Judge Stephen Friot’s ruling upholding the constitutionality of the state’s controversial execution protocol. Oklahoma began to execute prisoners before the Circuit Court could rule on the prisoners’ appeal. The state previously executed four prisoners while the federal trial on the drug protocol was pending. Among those slated for execution are prisoners with serious mental illness, intellectual disability, trauma, and significant claims of innocence. Oklahoma executed two seriously mentally ill prisoners without judicial review of their claims of mental incompetency and scheduled another for execution even though he was incarcerated in another jurisdiction and the state had not made arrangements for transfer of custody.

Alabama carried out — or attempted to carry out — several executions in 2022 in violation of its own law. When the Alabama legislature authorized nitrogen hypoxia as a method of execution in 2018, it afforded prisoners a narrow 30-day window in which to designate it, rather than lethal injection, as the means by which they would be put to death. Alabama prosecutors then selected for execution prisoners whom they believed had not designated nitrogen hypoxia as the method of their execution.

However, as the Alabama federal district court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit found, corrections officials “chose not to keep a log or list of those inmates who submitted an election form choosing nitrogen hypoxia” and lost or misplaced the election forms submitted by some death-row prisoners. Prison guards also collected, but did not turn in, forms submitted by other prisoners. Further, when it distributed the forms, ADOC provided no explanations of the form or assistance in filling it out to prisoners with intellectual impairments. In court proceedings over potential violations of condemned prisoners rights, the Alabama Attorney General’s office materially misrepresented the role prison officials played in the designation process and was sanctioned for its misconduct.

Lawyers for Matthew Reeves, an intellectually disabled death-row prisoner, alleged that he would have opted for execution by nitrogen gas and that Alabama’s failure to offer him accommodations for his intellectual disability violated his rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). After reviewing thousands of pages of documents and conducting a seven-hour hearing that included testimony from prison officials and a defense mental health expert, the district court concluded that Reeves had demonstrated a substantial likelihood that he would succeed on his ADA claim and issued a preliminary injunction barring the state “from executing [Reeves] by any method other than nitrogen hypoxia before his [ADA] claim can be decided on its merits.” A three-judge panel of the Eleventh Circuit unanimously affirmed the district court but in a 5 – 4 execution night vote on January 27, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the injunction and Reeves was executed.

Alan Miller

Alabama unsuccessfully attempted to execute Alan Miller on September 22 after he challenged the state’s authority to execute him by lethal injection. Miller alleged that he had designated execution by nitrogen hypoxia and requested a copy of the form, but Alabama prison officials said they had no record of his having submitted the form. Judge R. Austin Huffaker, Jr. of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama found that “Miller has presented consistent, credible, and uncontroverted direct evidence that he submitted an election form in the manner he says was announced to him by the [ADOC],” along with “circumstantial evidence” that ADOC lost or misplaced his form. Huffaker issued an injunction prohibiting the state from executing Miller by means other than nitrogen hypoxia and the Eleventh Circuit denied Alabama’s motion to vacate the district court’s ruling. In a 5 – 4 vote, the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the injunction and allowed the execution to proceed, but Miller’s execution was called off when the execution team was unable to set an IV line.

Defendants in two states brought challenges to the death-penalty jury selection process. Both argued that the combination of the “death-qualification” process — which disqualifies potential jurors from serving in a capital case because of their expressed opposition to the death penalty — and discretionary jury strikes discriminatorily disenfranchised African American jurors and produced unrepresentative juries incapable of reflecting the views of the community.

Brandon Hill

In North Carolina, lawyers for Wake County capital defendant Brandon Hill presented a study by law professors Catherine M. Grosso and Barbara O’Brien that documented statistically significant evidence of racial disparities in death-qualification. The study of eleven years of capital prosecutions in the county found that Black potential jurors were removed “at 2.16 times the rate of their white counterparts.” Controlling for jurors who could have been excused for cause on other grounds, they found that otherwise qualified “Black venire members were removed on this basis at 2.27 times the rate of white venire members.” The prosecution’s racially disparate exercise of discretionary peremptory strikes further diluted Black representation on death penalty juries. Grosso and O’Brien found that the prosecution peremptorily “struck Black potential jurors at 2.04 times the rate it struck white venire members.” Their research showed that “[t]he cumulative effect of the death qualification process and the state’s exercise of peremptory strikes meant that Black potential jurors were removed at almost twice the rate of their representation in the population of potential jurors,” while white jurors were removed at 0.8 times their representation in the general venire.

In Florida, lawyers representing Dennis Glover in his capital resentencing trial presented research from criminal justice professor Dr. Jacinta M. Gau, who reviewed the jury selection practices in the 12 capital cases tried in Duval County (Jacksonville) from 2010 through 2018. Dr. Gau found that 33.8% of Black potential jurors were excluded by death qualification, along with 38.0% of other jurors of color, while only 15.5% of white jurors were excluded. While Black jurors comprised 25.9% of the general venire, they constituted 39.3% of those disqualified because of their views against the death penalty. Likewise, while other jurors of color (Latinx, Asian, or other race) comprised 8.9% of the overall jury pool, they constituted 15.2% of those disqualified because of opposition to capital punishment. By contrast, white jurors comprised 65.4% of the entire venire, but only 45.5% of death-qualification strikes. Again, the prosecutor’s discretionary strikes compounded the racial disparities: “fully two thirds of Black women otherwise eligible, qualified, and willing to serve were excluded by the combination of death qualification and prosecutor peremptory strikes, as were 55% of Black men,” Gau wrote.

Research and Investigations

On June 29, 2022, timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Furman v. Georgia that ushered in the modern era of the U.S. death penalty, DPIC released our Death Penalty Census, our effort to identify and document every death sentence imposed in the U.S. since Furman. The census captures more than 9,700 death sentences imposed between the Furman ruling and January 1, 2021.

The data from the census document that 49 years into the modern era, the single most likely outcome of a death sentence imposed in the United States is by far that the defendant’s conviction or death sentence will be overturned and not re-imposed. Nearly half of the death sentences imposed since 1972 (49.9%) have been reversed as a result of court decisions. The next most likely outcome (23.9%) is that the sentence is still active, and the defendant is still on death row. By comparison, fewer than one in six (15.7%) death sentences have ended in execution. 7.3% of death sentences effectively became death-in-prison life sentences, as death-row prisoners died before their sentence was carried out or while their appeals were still pending in the courts. Another 2.9% of sentences were decapitalized by executive grants of clemency.

Our analysis of the data confirmed the increasing geographic arbitrariness of the U.S. death penalty and that it is disproportionately carried out in a small number of states and counties characterized by outlier practices and lack of meaningful judicial process. Fewer than 2.4% of all counties in the U.S. (just 75 counties) accounted for half of all death sentences imposed in state courts since 1972.

Prosecutions in just five counties accounted for more than 1/5 of all executions in the U.S., while prosecutions in just 2% of U.S. counties accounted for half of all U.S. executions. 84% of U.S. counties had not had any executions in a half-century.

Just 34 counties — fewer than 1.1% of all the counties in the U.S. — accounted for half of everyone on death row in U.S. state death rows. 2% of U.S. counties accounted for 60.8% of all state death-row prisoners. 82.8% of U.S. counties did not have anyone on death row.

Outlier practices disproportionately contributed to death sentences and executions. Counties in Alabama and Florida, which authorized non-unanimous death sentences, imposed more death sentences and had higher per capita death-sentencing rates and current death-row populations than other counties of similar size. States with the highest execution rates also tended to have the worst access to meaningful judicial review. More than 100 people were executed in Texas after U.S. Supreme Court case precedent had already established the unconstitutionality of their death sentences. 36.4% of all Florida executions, or 1 in every 2.75 executions, came despite U.S. Supreme Court decisions clearly establishing the unconstitutionality of their death sentences.

Our prosecutorial accountability project, the first results of which were also released on the 50th anniversary of Furman, found that official misconduct is rampant in death penalty cases. Our research, which is still ongoing, identified more than 550 cases in which a capital conviction or death sentence was overturned or a death-row prisoner was exonerated as a result of prosecutorial misconduct. That means that at least 5.6% of all death sentences that have been imposed in the United States since 1972 have been reversed because of prosecutorial misconduct or resulted in a misconduct-related exoneration.

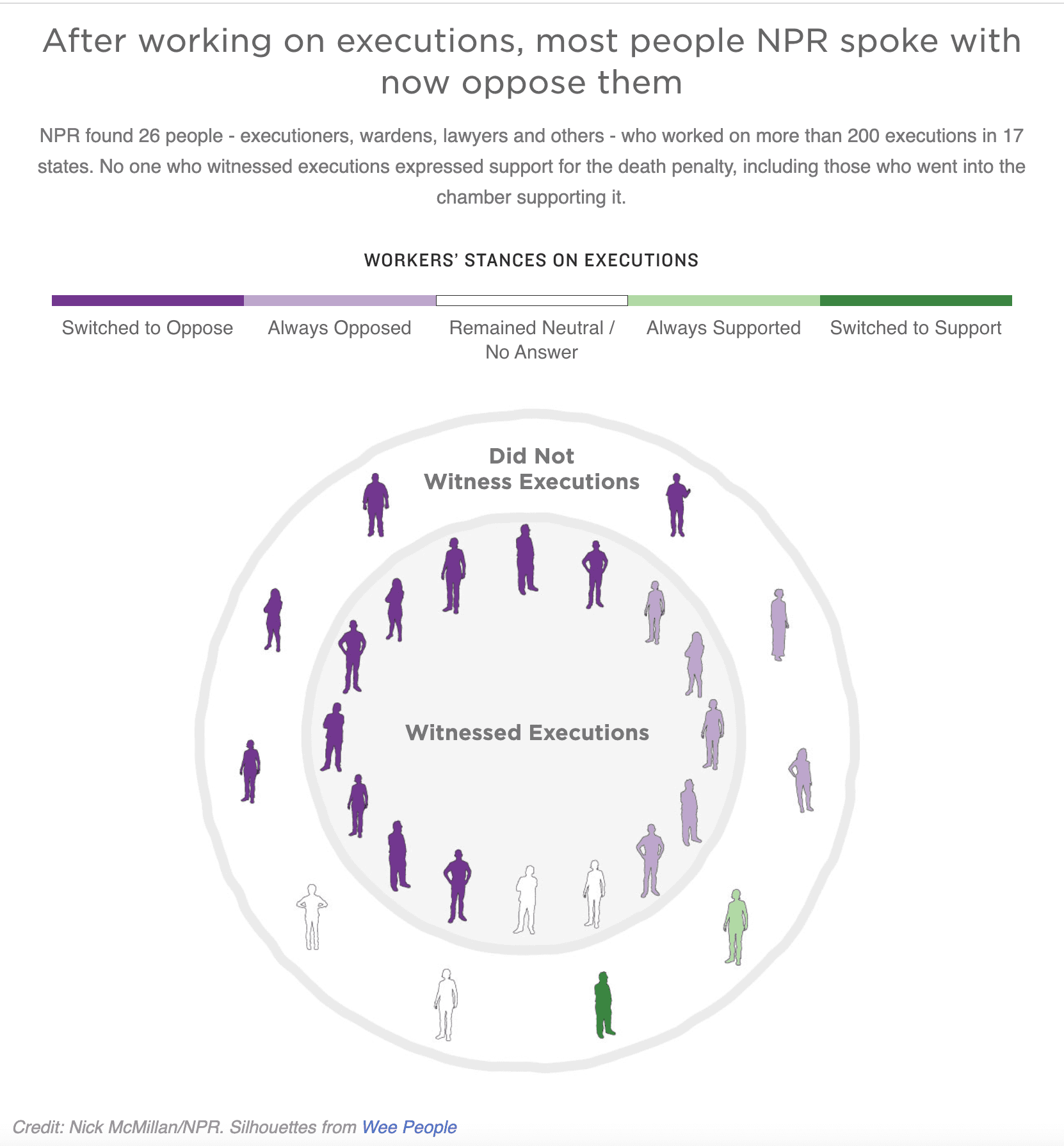

An important investigation by National Public Radio shined a light on one of the less appreciated consequences of capital punishment: its debilitating impact on the prison personnel who are tasked with carrying it out. Reporter Chiara Eisner interviewed 26 current or former corrections workers and others who had been involved in executions carried out by seventeen states and the federal government, finding that corrections personnel who participate in executing prisoners experience emotional trauma so profound that it often changes their views about capital punishment.

“Most of the workers NPR interviewed reported suffering serious mental and physical repercussions,” Eisner reported. “But only one person said they received any psychological support from the government to help them cope.” Of all the people whose work required them to witness executions in 13 states — Virginia, Nevada, Florida, California, Ohio, South Carolina, Arizona, Nebraska, Texas, Alabama, Oregon, South Dakota, and Indiana — none said they still support the death penalty, including those who were in favor of capital punishment when they started their jobs.

Execution and Sentencing Trends Top

Key Findings

- Eighth consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions and 50 new death sentences

- Two states – Oklahoma and Texas – performed 56% of the year’s executions

- No counties imposed more than a single death sentence

Executions by State

| State | 2022 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | 5 | 3 |

| Oklahoma | 5 | 2 |

| Arizona | 3 | |

| Alabama | 2 | 1 |

| Missouri | 2 | 1 |

| Mississippi | 1 | 1 |

| U.S. Federal Government | 3 | |

| Total | 18 | 11 |

For the eighth consecutive year, fewer than 50 new death sentences were imposed in the United States and fewer than 30 executions were carried out. Six states carried out executions, while twelve imposed new death sentences. With the exception of the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, the 20 new death sentences — just two above last year’s record low of 18 — were the fewest imposed in any year in the U.S. in the past half-century. The 18 executions also were fewer than in any pre-pandemic year since 1991.

Death sentences and executions have both fallen dramatically from their peak usage in the 1990s. Death sentences in 2022 were 93.7% below the peak of 315 in 1996. Executions have dropped by 82% since their peak of 98 in 1999. The number of people on death row across the country also declined for the 21st consecutive year, with resentencings to life or less again outpacing the number of new death sentences. As of April 1, there were 2,414 people on death row.

Geographically, the year’s trends were a microcosm of the last 50 years of the U.S. death penalty. Oklahoma and Texas performed more executions than any other states, combining for more than half (56%) of the year’s executions. Since 1976, those two states have performed about 45% of all executions in the U.S. At a county level, just 13 counties carried out executions, and just two — Oklahoma County, Oklahoma and Maricopa County, Arizona — carried out more than a single execution. Both of those counties are among the 20 most prolific executing counties in the last 50 years. Thirteen (65%) of the death sentences imposed in 2022 were handed down in the five states with the largest death row populations – California (2 new sentences), Florida (4), Texas (2), Alabama (3), and North Carolina (2), which also are the only states to impose multiple death sentences during the year.

Counties with the Most Death Sentences in the Last Five Years

| County | State | New Death Sentences 2018 – 2021 | New Death Sentences 2022 | Five-Year Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riverside | California | 5 | 5 | |

| Cuyahoga | Ohio | 5 | 5 | |

| Los Angeles | California | 4 | 4 | |

| Maricopa | Arizona | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Tulare | California | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma | 3 | 3 |

Oklahoma County’s four executions in 2022 brought its total to 46 since 1976. It now ranks fourth in the country in the number of executions, and no county outside of Texas is responsible for more. The five most prolific executing counties (the others, all in Texas, are Harris, Dallas, Bexar, and Tarrant) have carried out more than one-fifth of all executions in the U.S. in the last fifty years.

People of color were again overrepresented among those executed in 2022, as were cases involving white victims. Eight of the 18 prisoners executed were people of color: five were Black, one was Asian, one Native American, and one Latino. Five of the eight people of color (62.5%) were executed for killing white victims (3 Black defendants, one Latino, and one Native American). Only one of the 10 white defendants (10.0%), Benjamin Cole, was executed for killing a person of color (Native American), and no one was executed for an interracial murder of a Black victim.

Twelve states imposed new death sentences this year. Florida sentenced more people to death than any other states, with four.

The overlap between executing states and sentencing states illustrates the continued geographic narrowing of death penalty use. The six states that carried out executions in 2022 imposed 41% (9) of the year’s death sentences. Every state that performed an execution also imposed at least one new death sentence this year.

Just 35% of the 51 death warrants issued for 2022 were actually carried out. Ten executions were stayed for reasons including mental competency, intellectual disability, and probable innocence. Seventeen executions were halted by reprieve — 9 in Ohio, where executions have been on hold since 2019 over concerns about lethal injection, and 6 in Tennessee, where Governor Bill Lee halted executions this year to review the state’s execution protocols. Richard Glossip in Oklahoma received two reprieves to allow the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to review his request for an evidentiary hearing on new evidence of innocence. One prisoner died while his death warrant was pending. One execution date was removed. Two executions, both in Alabama, failed after execution personnel were unable to set IV lines. Two other warrants expired without being carried out because the condemned prisoner was not in custody in the state or the state had scheduled the execution without the drugs necessary to carry it out.

Oklahoma’s decision to schedule 25 execution dates over a two-year period marked it as an outlier, even among states that regularly perform executions. Only three states have ever executed 25 or more people in a two-year span — Texas, Oklahoma, and Virginia. If Oklahoma were to carry out all 25 executions, it would execute an unprecedented 58% of its death row in that time period.

Problems with execution methods halted executions in three states, while Ohio continued to pause executions for the same reason. In South Carolina, the state supreme court stayed the executions of Richard Moore and Brad Sigmon, who were challenging the state’s use of the electric chair and firing squad as execution alternatives to lethal injection. In court filings, Moore wrote, “I believe this election is forcing me to choose between two unconstitutional methods of execution. … Because the Department says I must choose between firing squad or electrocution or be executed by electrocution I will elect firing squad.” The state said that it had been unable to obtain lethal-injection drugs, leaving electric chair and firing squad as the available methods.

Tennessee Governor Bill Lee halted executions and ordered an independent investigation into the state’s execution procedures after it was revealed that corrections officers had not followed protocol in preparation for Oscar Smith’s execution on April 21. Lee called off Smith’s execution less than half an hour before it was set to be carried out. Lee emphasized the importance of an independent, third-party review, appointing a former U.S. Attorney to conduct the investigation.

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey similarly paused executions after her state’s string of botched and failed executions. In contrast to Lee, Ivey made no assurances that the “top-to-bottom review” she ordered would be performed by an independent investigator. Instead, she blamed the problems on efforts by prisoners and their attorneys to ensure that each case received thorough judicial review.

Ohio Governor Mike DeWine issued nine reprieves citing “ongoing problems involving the willingness of pharmaceutical suppliers to provide drugs” for use in executions “without endangering other Ohioans.” Drug manufacturers had informed the governor that they would halt selling medicines to state facilities if Ohio diverted drugs that had been sold for medical use and instead used them in executions.

Innocence and Clemency Top

Key Findings

- 190 people have been exonerated from death row since 1973

- Concerns about innocence attracted unlikely spokespeople, including Republican state legislators and self-described supporters of capital punishment

- Exonerations and claims of innocence centered on police and prosecutorial misconduct

Exonerations in 2022

Two more former death-row prisoners were in exonerated in 2022, including the third woman wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death. With DPIC’s ongoing research discovering two additional unrecorded exonerations, the number of U.S. death-row exonerations since 1972 rose to 190.

DPIC’s analysis of data from the National Registry of Exonerations also found that at least twelve innocent people were exonerated in 2021 from wrongful murder convictions that involved the wrongful pursuit or threatened use of the death penalty by police or prosecutors.

Samuel Randolph IV

Samuel Randolph IV was exonerated in April 2022 after being wrongfully incarcerated for 20 years. Randolph is Pennsylvania’s 11th death-row exoneree, with five of those exonerations occurring since 2019. All five of those exonerations have involved both official misconduct and perjury or false accusation. Four of the five have also involved inadequate legal representation at trial.

Randolph was sentenced to death in 2003 for the murders of two men in a Harrisburg bar in 2001. He had long maintained his innocence, alleging that police and prosecutors withheld exculpatory evidence in the case and selectively refused to test DNA evidence that could exclude him as the killer. He was represented at trial by a lawyer who, while running for district attorney in a neighboring county, had failed to investigate Randolph’s case. After a complete breakdown in communications between Randolph and appointed counsel, his family’s sale of property raised enough money to hire private counsel. However, the trial court refused to grant counsel even a three-hour continuance to accommodate a previously scheduled, unrelated court appearance. Randolph alleged that the court’s ruling violated his Sixth Amendment right to be represented by counsel of choice.

A federal district court held a hearing on these claims in 2019. In May 2020, it granted Randolph a new trial on the Sixth Amendment violation, mooting the necessity to address Randolph’s innocence claims. In July 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit upheld that ruling. Two days after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the county prosecutors’ appeal, District Attorney Fran Chardo filed a motion to terminate the prosecution of Randolph. Refusing to concede Randolph’s innocence, Chardo wrote that “retrial is not in the public interest at this time” because “[t]he police affiant and the police detective who handled the evidence collection in this case have both died” and “[o]ther witnesses have become unavailable for other reasons.”

In 2021, while the Dauphin County prosecutors’ request for review by the U.S. Supreme Court was pending, Chardo offered Randolph an “Alford” plea in which he could continue to maintain his innocence but would have to admit that prosecutors had sufficient evidence to convict. Under the deal, Randolph would be released for time served but his convictions would remain on his record. “I didn’t do this. Innocent people don’t plead guilty — as bad as I want to go home,” Randolph told Penn Live.

Marilyn Mulero at a news conference regarding her exoneration.

In August 2022, a Cook County, Illinois judge granted a motion filed by State’s Attorney Kim Foxx to dismiss all charges against Marilyn Mulero, who was framed for the murder of an alleged gang member by disgraced former Chicago detective Reynaldo Guevara. Mulero’s was one of seven cases Foxx moved to dismiss, but the only case in which a defendant had been sentenced to death. Two additional people framed for murder by Guevara have since been exonerated.

Guevara has been accused of framing defendants of murder in more than 50 cases by beating, threatening, and coercing suspects to obtain false confessions. Thirty-three wrongful convictions tied to Guevara’s misconduct have been overturned to date, including death-row exoneree Gabriel Solache in 2017.

Mulero’s case follows the same pattern. In 1992, she was interrogated by Guevara and former Chicago Police Detective Ernest Halvorsen over the course of a 20-hour period, during which she was denied sleep and access to counsel and was threatened with the death penalty and the loss of her two children if she did not confess. She eventually signed a statement prepared by the detectives confessing to one of two murders of gang members who were thought to have been shot in retaliation for a prior gang killing.

After the trial court denied her motion to suppress the confession, Mulero’s court-appointed lawyer advised her to plead guilty, which she did in September 1993. A jury was empaneled for the sentencing phase of trial and sentenced her to die. In May 1997, the Illinois Supreme Court overturned her conviction because her trial prosecutor improperly cross-examined her about the suppression motion and then argued to the jury that her answers indicated a failure to express remorse. She was resentenced to life without parole in 1998.

Governor J.B. Pritzker commuted her sentence to time served in April 2020, after Mulero had spent 28 years in prison, five of them on death row. She is the third female death-row exoneree in the U.S. since 1973 and the 16th exoneree from Cook County — the most of any county in America. At least 14 of the Cook County exonerations have involved official misconduct by police or prosecutors, and eight have involved coerced false confessions.

DPIC’s 2021 report, The Innocence Epidemic, explains that Cook County’s then 15 death-row exonerations “are directly related to endemic police corruption, as the notorious ‘Burge Squad,’ operating under Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge, and disgraced Chicago detective Reynaldo Guevara systematically tortured or coerced innocent suspects into confessing to murders they did not commit. Illinois’ high rate of wrongful convictions in death cases was a major factor in the state’s 2011 repeal of capital punishment, as state officials decided there was no way to correct the inaccuracy of the state’s death penalty system.”

DPIC also added two California cases to its Exoneration List: Eugene Allen, who was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a prison guard in 1976 and acquitted on retrial in 1981; and Barry Williams, wrongfully convicted in 1986 and exonerated in 2021 of an allegedly gang-related street shooting in Los Angeles. Official misconduct was present in both of their cases.

All four exonerees are people of color: Randolph, Allen, and Williams are Black; Mulero is Latina. Nearly two-thirds of all U.S. death-row exonerees have been people of color (123 of 190, 64.7%). 54.2% percent are Black; 8.9% are Latinx.

DPIC’s review of National Registry of Exonerations data from 2021 once again found that the use or threat of the death penalty by police or prosecutors led to wrongful convictions in numerous other cases in which the death penalty was not imposed. Of the seven wrongful capital prosecutions that resulted in exonerations in 2021, three resulted in death sentences (Sherwood Brown and Eddie Lee Howard in Mississippi and Barry Williams in California.) Juries in three other states sentenced other wrongfully capitally prosecuted defendants to life without parole — James Allen in Illinois, George Bell in New York, and Devonia Inman in Georgia. In the seventh wrongful capital prosecution, Georgia prosecutors secured a murder conviction against Dennis Perry and then used the threat of an imminent penalty-phase trial to coerce him to agree to waive any guilt-phase appeals in exchange for being spared the death penalty. In five exonerations in non-capital murder prosecutions, witnesses who had pled guilty to avoid the death penalty or had been threatened with the death penalty if they did not cooperate provided false testimony that led to wrongful murder convictions.

Official misconduct was the leading cause of the wrongful convictions, present in 10 of the 12 exonerations. Race was also a significant factor: six of the seven who were wrongfully capitally prosecuted — and all three who were sentenced to death — are Black; overall, nine of the exonerees are African American. The exonerees averaged 26.5 years between conviction and exoneration, collectively losing more than 300 years to the wrongful convictions. But African-American exonerees averaged 27.8 years from conviction to exoneration, nearly 23% longer than the average of 22.7 years it took to clear white exonerees.

Innocence Claims Prompt Execution Deferrals, Garner Bipartisan Support from Lawmakers

Richard Glossip

Richard Glossip, who has long maintained his innocence, received two reprieves this year from Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt following significant findings of innocence from an independent investigation into his case. Stitt issued the first 60-day reprieve in August 2022, pushing Glossip’s September 2022 execution date to December 2022, to provide time for the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (OCCA) to determine whether to grant an evidentiary hearing to address innocence claims. Stitt granted a second reprieve on November 2, 2022, again “to allow time for OCCA to address pending legal proceedings,” resetting Glossip’s December 2022 execution date to February 2023. Later in November, after the second reprieve, the OCCA twice denied Glossip’s petitions for a hearing to review evidence on his innocence claims.

In May 2021, 28 Republican and six Democratic Oklahoma legislators called upon Governor Stitt and the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board to conduct an independent investigation into Glossip’s case, after his lawyers had uncovered new evidence supporting his claims of innocence. Glossip was originally sentenced to death for the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese, his boss at an Oklahoma City motel. The prosecution had no physical evidence linking him to the crime, only the self-serving testimony of his co-defendant, Justin Sneed, who was able to avoid the death penalty by claiming that Glossip had hired him to commit the crime.

Oklahoma Representative Kevin McDugle speaking at a June 15, 2022 press conference announcing the release of the independent investigation into Richard Glossip’s case.

The legislators subsequently commissioned an independent pro bono investigation by the national law firm, Reed Smith, LLP. Days before the release of the law firm’s report, which exposed significant evidence of government misconduct and destruction of evidence, Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor filed a motion to set execution dates for Glossip and 24 other death-row prisoners. On July 1, 2022, the same day that Glossip’s lawyers filed a motion for an evidentiary hearing on his innocence claim, the state court set the 25 execution dates, scheduling an execution nearly every month from August 2022 through December 2024.

Since 2014, Glossip has been scheduled for execution eight times, and he has been served his last meal three separate times. He received a last-minute reprieve from then-Governor Mary Fallin in September 2015 when it was revealed that the state had obtained an incorrect drug for the execution. Glossip’s case has not only received bipartisan support from state legislative officials but has also been examined by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR), which issued a precautionary measure in favor of Glossip in March 2022. In a press release on the issuance of the precautionary measure, the IACHR identified Glossip’s 23 years in solitary confinement and the repeated, and often last-minute, postponement of scheduled executions as “conditions of detention incompatible with international human rights standards.”

After the OCCA denied Glossip’s motions to permit him to present his new evidence of innocence in court, State Representative Kevin McDugle (R‑Broken Arrow), who led the call for an investigation, authored a blistering op-ed in The Oklahoman saying: “if the [Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals] cannot grant a hearing on this flimsy death penalty conviction, my confidence as a legislator in our state’s judicial system, and its ability to make just decisions and take responsibility for its failures, has been destroyed. … Who will take responsibility for this travesty? Where is the backbone that will stand for justice? The members of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals have let us all down. I pray new leadership in the offices of the attorney general and Oklahoma County district attorney find the strength to do what is needed to right this terrible wrong. We cannot kill an innocent man!”

Melissa Lucio

The innocence case of Texas death-row prisoner Melissa Lucio has also been the subject of international attention and bipartisan legislative action. Lucio was sentenced to death in 2008 on charges that she allegedly beat her two-year-old daughter, Mariah, to death. Lucio’s lawyers, with the support of expert testimony, have presented expert affidavits that Mariah was not murdered at all, but likely died from head trauma following an accidental fall two days prior to her death. The victim of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse from a young age, Lucio has been diagnosed with PTSD, battered woman syndrome, and depression, and has intellectual impairments, all of which, forensic and domestic abuse experts say, made her more vulnerable to coercive interrogation. After five hours of aggressive questioning by police on the night of Mariah’s death, Lucio acquiesced to police pressure, saying, “I guess I did it.”

In July 2019, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturned Lucio’s conviction, one of only two times the court had granted relief in more than 150 appeals of Texas death sentences imposed this century. However, in February 2021, the full Circuit voted 10 – 7 to reconsider that opinion and reinstated her conviction and death sentence. Supported by amicus briefs filed by a broad coalition of advocates for victims of domestic and gender-based violence, former prosecutors, legal scholars, and innocence organizations, Lucio sought review in the U.S. Supreme Court. However, in October 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court denied review of Lucio’s case.

Texas then scheduled Lucio’s execution for April 27, 2022. In response, Lucio filed a motion to vacate the death sentence and remove the judge and district attorney in her case because of conflicts of interest stemming from their employment of key members of Lucio’s original defense team.

In February, the IACHR granted Lucio a precautionary measure asking the state to refrain from execution until her case is reviewed and to ensure detention conditions align with international human rights standards. Lucio, who has spent 14 years in solitary confinement, is housed in a concrete room the size of a parking space in a building containing female prisoners who suffer from extreme mental illness. Lucio “hears screaming, cursing, banging, and slamming doors throughout the prison,” and is frequently exposed to “airborne chemical agents, which are used to subdue prisoners who are deemed to be acting out,” according to her petition.

Texas Representative Jeff Leach (R‑Plano) at a press conference for Melissa Lucio.

In March, nearly 90 members of the Texas House of Representatives from across the political spectrum, led by Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Plano) issued a call for the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and Governor Greg Abbott to grant clemency to Lucio. Her clemency petition included statements of support from jurors, forensic and medical experts, anti-domestic violence activists, religious leaders, exonerees, and Lucio’s siblings and children. In a heated legislative hearing, Leach and other legislators pressed Cameron County District Attorney Luis Saenz to withdraw Lucio’s death warrant. He ultimately agreed to do so if the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) did not first issue a stay.

Days before the scheduled execution, as the state Board of Pardons and Paroles was set to consider Lucio’s clemency petition, the TCCA stayed Lucio’s execution and granted her review of four issues: that prosecutors obtained her conviction using false testimony, that the jury’s exposure to previously unavailable scientific evidence would have resulted in her acquittal, that she is in fact innocent, and that prosecutors suppressed favorable evidence that was material to the outcome of her trial. The court granted the stay “pending resolution of the remanded claims.”

Clemency

Gerald Pizzuto Jr.

On December 13, Oregon Governor Kate Brown announced she would grant clemency to all 17 people on the state’s death row. “I have long believed that justice is not advanced by taking a life, and the state should not be in the business of executing people — even if a terrible crime placed them in prison,” Brown said. She described her action as “consistent with the near abolition of the death penalty” by the state legislature in 2019, when it enacted a new law that significantly limited the circumstances in which the death penalty could be applied. The Oregon Supreme Court then declared that the use of the death penalty against those whose crimes were no longer subject to capital punishment violated the Oregon constitution’s prohibition against disproportionate punishment, a ruling that experts said would effectively clear death row. Brown’s blanket commutation was the seventh time in the last 50 years that a governor had commuted all of a state’s death sentences. Governor Mark Hatfield also commuted the sentences of all of Oregon’s death-row prisoners after voters passed a statewide referendum abolishing capital punishment in 1964.

The case of terminally ill death-row prisoner Gerald Pizzuto Jr., put the Idaho governor and pardons board at odds, forcing the state supreme court to intervene in the matter. Pizzuto, who experienced a traumatic childhood characterized by chronic severe physical and sexual abuse, suffers from late-stage bladder cancer, chronic heart and coronary artery disease, coronary obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and Type 2 diabetes with related nerve damage to his legs and feet. In December 2021, the Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole voted 4 – 3 to recommend clemency for Pizzuto. The following day, Governor Brad Little rejected the recommendation, leading to a legal battle over his constitutional authority to do so.

An Idaho trial court ruled on February 4, 2022 that Little did not have the power to reject the board’s clemency ruling and vacated Pizzuto’s death sentence, only to have it later reinstated by the Idaho Supreme Court in an August 23 ruling. Prosecutors then sought and obtained a new death warrant, setting Pizzuto’s execution for December 15. On November 30, the Director of the Idaho Department of Corrections provided notice that the state was unable to obtain the lethal drugs necessary to carry out the execution, and the state attorney general’s office notified the court that the state would allow Pizzuto’s death warrant to expire.

Resentencing of Pervis Payne

Pervis Payne embracing his attorney Kelley Henry.

After decades of litigation, Tennessee death-row prisoner Pervis Payne, who has long maintained his innocence, was found to be ineligible for the death penalty because of intellectual disability and in January 2022 was resentenced to two concurrent life sentences. Payne, who has been in prison for 34 years, will be eligible to apply for parole in five years. Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich, who had opposed DNA testing of evidence Payne said could prove his innocence and had fought granting him a hearing to prove his ineligibility for the death penalty, later conceded that he was intellectually disabled. However, she argued to the court that he should be resentenced to two consecutive life sentences, effectively condemning him to death in prison.

International bodies have routinely encouraged the suspension and abolition of death sentences for those with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities, as noted by both the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Although the 2002 U.S. Supreme Court case Atkins v. Virginia established the unconstitutionality of executing people with intellectual disability, many states, including Tennessee, have been slow to implement the exemption retroactively. Scheduled for execution in December 2020, Payne received a reprieve because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Tennessee legislature subsequently passed new legislation that went into effect in May 2021 that allowed Payne, whose IQ scores place him within the intellectually disabled range, to petition the court to vacate his death sentence.

Payne, who is Black, was convicted and sentenced to death in 1987 for the murders of a white 28-year-old woman and her 2‑year-old daughter. In a trial marred by prosecutorial misconduct and racial bias, prosecutors alleged without evidence that Payne — a pastor’s son with no prior criminal record, no history of drug use, and no history of violence — had been high on drugs and committed the murder after the victim rebuffed his sexual advances. After a 2019 court order compelled the state to provide the defense access to evidence, DNA testing identified the DNA of the two victims and an unknown male on the handle and blade of the knife used. Payne’s DNA was found only on a portion of the knife that was consistent with his account of how he had tried to assist the victims.

Problematic Executions Top

Key Findings

- Significant problems in executions and attempted executions marked 2022 as the year of the botched execution

- 72% of prisoners executed in 2022 had evidence of a significant impairment

- Half of those executed had spent 20 years or more on death row, in violation of international human rights norms

Alongside the systemic problems that have become commonplace in U.S. executions — vulnerable defendants, claims of innocence, inadequate defense, and denial of meaningful judicial review — 2022 featured a shocking number of botched and failed executions. In what could be categorized as “The Year of the Botched Execution,” significant problems were reported in all three of Arizona’s executions, and Alabama’s executions went so wrong that Governor Kay Ivey paused all executions and ordered a “top-to-bottom review” after one execution resulted in “carnage” and the remaining two had to be called off when execution personnel repeatedly failed to establish an IV line.

Several states scheduled executions in violation of their own protocols, without the means to carry them out, or without making arrangements to obtain custody of a person incarcerated in another jurisdiction. A South Carolina trial court struck down that state’s attempted use of the electric chair and firing squad as alternatives to lethal injection, and Tennessee Governor Bill Lee halted all executions in his state and appointed an independent counsel to investigate major failures by corrections officials to comply with the state’s execution protocol.

As in past years, the vast majority of those executed in 2022 were individuals with significant vulnerabilities. At least 13 of the 18 people executed in 2022 had one or more of the following impairments: serious mental illness (8); brain injury, developmental brain damage, or an IQ in the intellectually disabled range (5); and/or chronic serious childhood trauma, neglect, and/or abuse (12). Three prisoners were executed for crimes committed in their teens: Matthew Reeves and Gilbert Postelle were 18 at the time of their crimes; Kevin Johnson was 19. At least four of the people executed this year were military veterans: John Ramirez, Benjamin Cole, Richard Fairchild, and Thomas Loden Jr.

The people executed in 2022 reflected the aging death-row population in the U.S. Six of the 18 people executed were age 60 or older. Carl Buntion, who was 78 years old when he was executed in Texas, was the third-oldest person ever executed in the United States. Five had significant physical disabilities, including Clarence Dixon, who was blind, and Frank Atwood, who used a wheelchair as a result of a degenerative spinal condition. Half (9) of those executed in 2022 had spent at least 20 years on death row, a period of time that has been recognized by international human rights bodies as constituting “excessive and inhuman” punishment, in violation of U.S. human rights obligations. Though these lengthy stays on death row are often the result of legally necessary appeals, the isolation, poor access to healthcare, and harsh conditions exacerbate prisoners’ physical and mental health conditions.

Donald Grant

Donald Grant was executed in Oklahoma on January 27 using a lethal-injection protocol that, at the time, was still under review by a federal court. He would be the first of four people executed in 2022 who were convicted in Oklahoma County, raising the county’s execution total to 46, the fourth most of any U.S. county in the past half-century. Grant’s lawyers had asked the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board to commute his death sentence, citing his diagnosis with schizophrenia and his brain damage. “Executing someone as mentally ill and brain damaged as Donald Grant is out of step with evolving standards of decency,” they argued at his clemency hearing. The board voted 4 – 1 to deny commutation.

Matthew Reeves

Matthew Reeves, the second prisoner executed in 2022, raised claims that he was ineligible for execution because he was intellectually disabled and that Alabama had violated the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by failing to offer him accommodations for his disability in order to allow him to select his method of execution. A federal appeals court had overturned Reeves’ death sentence in part because his trial lawyer failed to present expert testimony on his intellectual disability, but the U.S. Supreme Court, voting along partisan lines, reversed that decision in 2021. The Court also rejected, in a 5 – 4 decision issued 1½ hours after his execution was scheduled to begin, a claim that the state had violated Reeves’ rights under the ADA when it distributed a form to death-row prisoners requiring them to choose between lethal injection and nitrogen hypoxia. The form required an 11th-grade reading level to understand. However, Reeves, who had an IQ in the upper 60s to low 70s and read at a first-grade level, was offered no assistance in completing the form. When Reeves did not fill out the form, prosecutors sought and obtained a death warrant scheduling his execution by lethal injection. No one who elected nitrogen suffocation was scheduled for execution. A federal district court issued an injunction, finding that Reeves had demonstrated substantial likelihood of success on the merits of his claim, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit upheld the injunction. Five justices on the U.S. Supreme Court voted to lift the injunction, allowing Alabama to execute Reeves.

Gilbert Postelle

Gilbert Postelle was 18 years old, intellectually impaired, mentally ill, and addicted to methamphetamines when, at the direction of his mentally ill father, he, his brother, and a fourth man participated in the fatal shootings of four people. His father delusionally believed that one of the men had been responsible for a motorcycle accident that had left the father seriously brain damaged. Postelle was sentenced to death for two of the shootings — the only person sentenced to death for the killings. His father was found incompetent to stand trial, and the others received life sentences. Oklahoma executed Postelle on February 17, just 11 days before a federal judge began hearing evidence on the constitutionality of the state’s execution protocol.

Carl Buntion

Carl Buntion was Texas’ oldest death-row prisoner and, just days before his scheduled April 21 execution, had been taken to the hospital suffering from pneumonia and blood in his urine. In his clemency petition, which was denied on April 19, his lawyers wrote, “Mr. Buntion is a frail, elderly man who requires specialized care to perform basic functions. He is not a threat to anyone in prison and will not be a threat to anyone in prison if his sentence is reduced to a lesser penalty.” Counsel noted that Buntion “ha[d] been cited for only three disciplinary infractions” in his 31 years on death row, “and [had] not been cited for any infraction whatsoever for the last twenty-three years.” They argued that his death sentence had been based on a prediction of future dangerousness that had proven false over his three decades of incarceration.

Carman Deck

Missouri executed Carman Deck after his death sentence had been overturned three separate times. In the decade between his initial death sentence and his third sentencing hearing in 2008, several mitigation witnesses had died or could no longer be located. That delay, a federal district judge ruled, “prevented the jury from adequately considering compassionate or mitigating factors that might have warranted mercy.” He was granted relief for the third time in 2017. On appeal, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit reversed that ruling on a technicality, holding that Deck’s claim was procedurally defaulted because his post-conviction lawyer had failed to raise the issue in state court. It further ruled that because the law on the issue had not been settled at the time of Deck’s resentencing, post-conviction counsel’s failure to raise the issue was not ineffective, and Deck therefore could not establish grounds to excuse the procedural default. In a stay application that was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court, Deck’s lawyers argued that “[a] state should not be allowed to repeatedly attempt to obtain a death sentence, bungle the process, and then claim victory when no one is left to show up for the defendant at the mitigation phase.” Deck’s petition seeking review of his case called the situation “an egregious example of what happens when the state repeatedly violates the rights of a capital defendant. The state’s earlier failures directly prevented Mr. Deck from presenting a compelling mitigation case at his third resentencing.”

Clarence Dixon

On May 11, Arizona executed Clarence Dixon, a severely mentally ill man. In 1978, then-Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Sandra Day O’Connor, later a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, had found Dixon not guilty by reason of insanity on unrelated charges. Judge O’Connor had directed Maricopa County prosecutors to make arrangements for Dixon’s continued custody until civil commitment proceedings, which were scheduled to start within ten days, could begin. Instead, Dixon was released, and two days later committed the offense for which he was executed. Dixon was not connected to the murder for two decades, and at his 2008 capital trial, he was permitted to fire his court-appointed attorneys and represent himself. At trial, Dixon presented a convoluted defense based upon his delusional belief that the charges against him were fueled by a government conspiracy. Despite counsel’s presentation of evidence that Dixon suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, with accompanying auditory and visual hallucinations and delusional thinking, and was now blind, a judge found him competent to be executed.

Dixon’s lawyers also challenged Arizona’s execution process and the drugs it intended to use in the state’s first execution attempt since the botched two-hour execution of Joseph Wood on July 23, 2014. In court proceedings in advance of the execution, assistant federal defender Jennifer Moreno argued that “[t]he state has had nearly a year to demonstrate that it will not be carrying out executions with expired drugs but has failed to do so.” Describing Dixon as “a severely mentally ill, visually disabled, and physically frail member of the Navajo Nation,” which opposes capital punishment, she said his execution would be “unconscionable.”

After an execution experts said was botched, witnesses described how Department of Corrections personnel failed for 25 minutes to set an intravenous line in his arms before performing a bloody and apparently unauthorized “cutdown“ procedure to insert the IV line into a vein in his groin. Defense lawyers said that the problems were exacerbated by the lack of transparency about Arizona executions. Dixon’s lawyer, assistant federal public defender Amanda Bass, said “[s]ince Arizona keeps secret the qualifications of its executioners, we don’t know whether the failure to set two peripheral lines in Mr. Dixon’s arms was due to incompetence, which resulted in the unnecessarily painful and invasive setting of a femoral line.”

Frank Atwood

Less than a month later, on June 8, Arizona executed Frank Atwood, who maintained his innocence in the 1984 kidnapping and murder of Vicki Hoskinson. In 2021, Atwood’s lawyers had discovered an FBI memo about an anonymous call the Bureau had received reporting that, after her disappearance, Hoskinson had been seen in a vehicle connected to an alternative suspect. A federal appeals court denied him a hearing on his claims of innocence and that the prosecution had unconstitutionally withheld exculpatory evidence from the defense.

In what Arizona Republic reporter Jimmy Jenkins called a “surreal spectacle,” Atwood helped prison officials find a suitable vein for the IV line during his execution. Jenkins wrote, “I have looked behind the curtain of capital punishment and seen it for what it truly is: a frail old man lifted from a wheelchair onto a handicap accessible lethal injection gurney; nervous hands and perspiring faces trying to find a vein; needles puncturing skin; liquid drugs flooding a man’s existence and drowning it out.” When the execution team was struggling to set the IV line, Atwood first suggested they try his right arm, then his hand, stopping them from their stated intention to establish an IV line in his femoral vein as they had done in Dixon’s execution.

Joe James Jr.

Continuing the series of botched executions, Alabama killed Joe James Jr. on July 28 over the strenuous opposition of the victim’s family. The daughters and brother of murder victim Faith Hall urged Governor Kay Ivey to halt James’ execution. Helvetius Hall, Faith’s brother, said, “Taking [James’] life is not going to bring Faith back. It ain’t going to make no closure for us.”

James was representing himself at the time of his execution. His execution began with an unexplained three-hour delay, which Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) officials later obliquely indicated involved difficulties setting an IV line. While media witnesses were waiting for the execution, corrections officials subjected two female journalists, both of whom had previously witnessed multiple executions, to embarrassing dress code inspections. AL.com reporter Ivana Hrynkiw was told that her skirt, which she had worn to witness three previous executions, was “too short.” After changing into clothing borrowed from a cameraman from another media outlet, she was then told she couldn’t wear open-toed shoes because they were “too revealing,” so she retrieved a pair of sneakers from her car. Hrynkiw’s employer, the Alabama Media Group, sent a formal complaint the next day, calling ADOC’s conduct “sexist and an egregious breach of professional conduct.”

The clothing inspections diverted attention from the state’s repeated failures to set an IV line, as a later private autopsy revealed. In the words of Atlantic writer Elizabeth Bruenig, who had facilitated and witnessed the private autopsy, “[s]omething terrible had been done to James while he was strapped to a gurney behind closed doors without so much as a lawyer present to protest his treatment or an advocate to observe it.” Bruenig wrote of “carnage” on James’ body, that his “hands and wrists had been burst by needles, in every place one can bend or flex” during what she called a “lengthy and painful death.” When the execution chamber curtains were opened three hours after the scheduled start of James’ execution, he was motionless and non-responsive. Anesthesiologist Joel Zivot, who witnessed the private autopsy, noted that there were puncture wounds, accompanied by bruises, throughout James’ arms, and bruising around the knuckles and wrists that suggested that execution team members tried and failed to insert IV lines in those locations. They also found puncture wounds in James’ musculature, “not in the anatomical vicinity of a known vein.” “It is possible that this just represents gross incompetence, or some, or one, or more of these punctures were actually intramuscular injections,” Zivot wrote, noting that such an injection “in this setting would only be used to deliver a sedating medication.”