In a new law review article, Professor Anna VanCleave of the University of Connecticut School of Law argues that the “heightened standards” of due process protection for capital defendants, required under the Eighth Amendment, are in practice no more than “a veneer of legitimacy and procedural caution” that fail to vindicate defendants’ rights. Professor VanCleave found that in the absence of clear guidance from the Supreme Court as to the actual meaning of “heightened standards,” lower courts apply the same standards used in non-capital criminal cases or even relax rules in favor of the State.

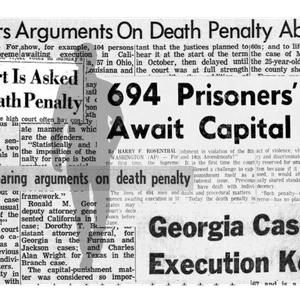

Professor VanCleave posits that the “heightened standards” principle was “set up to fail” based on its origins in inconsistent jurisprudence. The Supreme Court held that due process required greater protections in capital cases, including the appointment of counsel, for the first time in Powell v. Alabama (1932), the infamous “Scottsboro Boys” case involving the wrongful conviction of nine Black youth for the rape of two white women. Since then, the Court consistently noted that “death is different,” finding, for instance, in Lockett v. Ohio (1978) that the “qualitative difference between death and other penalties calls for a greater degree of reliability when the death sentence is imposed.” However, the Court has also held that the due process right in all criminal cases is narrow, rejecting the use of a robust three-pronged test it developed under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment for civil cases. Instead, the Court maintains that a rule of criminal procedure will only be struck down if it “offends some principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.” To resolve the tension between a narrow right overall and an expanded right in capital cases, the Court held that heightened standards in capital cases arose from the Eighth Amendment when it reinstated the death penalty after a four-year pause in 1976. The Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishments but contains no language about procedural review of criminal cases, capital or otherwise. Professor VanCleave found that the Court “offered no blueprint for how lower courts should apply heightened standards or how appellate courts should determine whether heightened standards had, in fact, been applied.”

Reviewing lower court decisions, Professor VanCleave found that “courts that invoke heightened standards frequently do so while clearly applying the exact same legal test that would apply in noncapital cases.” She attributes this incongruity to the limits of the narrow “fundamental” test. The Court has found at least fifty separate procedural protections to be “fundamental” in criminal cases and developed an analytical doctrine for each, while failing to provide a specific unifying test for criminal cases overall. As a result, Professor VanCleave argues, courts reviewing a capital case must analyze dozens of potential procedural rules with endless factual variations and decide how each specific rule should receive “heightened scrutiny” because death is involved. She found that most courts took the easier path of noting that “death is different” at the beginning of an opinion, applying the rules already elucidated by the Supreme Court in non-capital cases, and mentioning the “heightened standards” in conclusion without ever explaining how those rules had been applied more strictly for the capital case.

Professor VanCleave further found that “the requirement of heightened reliability often not only adds little or no meaningful process but can actually undermine certain specific rights of capital defendants.” For instance, courts have used the notion that capital cases receive heightened scrutiny to justify relaxed standards for the State when introducing penalty phase evidence. In Lezmond Mitchell’s case, Professor VanCleave describes how prosecutors were permitted to argue that “his status as a Navajo was a reason to impose a death sentence because the murder of other Navajo members represented a betrayal of his religious and cultural traditions.” In fact, Navajo leaders openly called for Mr. Mitchell’s sentence to be commuted to life without parole. Mr. Mitchell challenged the evidentiary rules as unconstitutional, but the Ninth Circuit rejected his argument, holding that “the Supreme Court has…made clear that in order to achieve ‘such heightened reliability,’ more evidence, not less, should be admitted on the presence of aggravating and mitigating factors.” Mr. Mitchell was executed by the federal government on August 26, 2020.

Professor VanCleave concludes that the “heightened standards” principle is “too generic,” creating “a false confidence in the procedural rigor of capital prosecutions.” Instead of a “meaningful, systematic definition,” capital defendants must rely on “a series of ad hoc decisions that prohibit or require a few specific procedures, but no larger scheme of regulation, and no guidance on how to fill the gaps of procedural regulation not specifically addressed by the Supreme Court.” She argues that the standard will only have teeth if it clarifies how specific procedures apply differently or draw more scrutiny in capital cases; otherwise, she suggests, the death penalty falls short of the promise of legitimacy offered by the Court in 1976. She quotes scholar Robert Cover, writing in 1986: “The Court continued to say that death was permissible if you get it right. And almost all the individual cases continued to confirm that the state could not get it right.”

Anna VanCleave, The Illusion of Heightened Standards in Capital Cases, University of Illinois Law Review (April 3, 2023).

United States Supreme Court

Oct 08, 2024

United States Supreme Court Will Consider Significance of Prosecutor’s Confession of Error in Glossip v. Oklahoma

United States Supreme Court

Sep 16, 2024

NEW RESOURCE: American Bar Association Reports on Capital Punishment and the State of Criminal Justice 2024

History of the Death Penalty

May 15, 2024