The Death Penalty in Black and White: Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Decides

- Executive Summary

- The Sounds of Racism

- The Raw Data

- Taking Into Account the Severity of Murders

- Mid-Range Cases Versus Extreme Cases

- Black Defendants and the Race of the Victims

- Philadelphia Study: Conclusions

- National Patterns of Race Discrimination

- Figure 7: Statistical Data in Death Penalty States Showing a Risk of Racial Discrimination 23

- No Relief in the Courts

- Study II: The Race of the Decision-Makers

- Racial Bias Permeates the System

- Public Reaction

- Conclusion

- Appendix

It is tempting to pretend that minorities on death row share a fate in no way connected to our own, that our treatment of them sounds no echoes beyond the chambers in which they die. Such an illusion is ultimately corrosive, for the reverberations of injustice are not so easily confined.

Executive Summary Top

The results of two new studies which underscore the continuing injustice of racism in the application of the death penalty are being released through this report. The first study documents the infectious presence of racism in the death penalty, and demonstrates that this problem has not slackened with time, nor is it restricted to a single region of the country. The other study identifies one of the potential causes for this continuing crisis: those who are making the critical death penalty decisions in this country are almost exclusively white.

From the days of slavery in which black people were considered property, through the years of lynchings and Jim Crow laws, capital punishment has always been deeply affected by race. Unfortunately, the days of racial bias in the death penalty are not a remnant of the past.

Two of the country’s foremost researchers on race and capital punishment, law professor David Baldus and statistician George Woodworth, along with colleagues in Philadelphia, have conducted a careful analysis of race and the death penalty in Philadelphia which reveals that the odds of receiving a death sentence are nearly four times (3.9) higher if the defendant is black. These results were obtained after analyzing and controlling for case differences such as the severity of the crime and the background of the defendant. The data were subjected to various forms of analysis, but the conclusion was clear: blacks were being sentenced to death far in excess of other defendants for similar crimes.

A second study by Professor Jeffrey Pokorak and researchers at St. Mary’s University Law School in Texas provides part of the explanation for why the application of the death penalty remains racially skewed. Their study found that the key decision makers in death cases around the country are almost exclusively white men. Of the chief District Attorneys in counties using the death penalty in the United States, nearly 98% are white and only 1% are African-American.

These new empirical studies underscore a persistent pattern of racial disparities which has appeared throughout the country over the past twenty years. Examinations of the relationship between race and the death penalty, with varying levels of thoroughness and sophistication, have now been conducted in every major death penalty state. In 96% of these reviews, there was a pattern of either race-of-victim or race-of-defendant discrimination, or both. The gravity of the close connection between race and the death penalty is shown when compared to studies in other fields. Race is more likely to affect death sentencing than smoking affects the likelihood of dying from heart disease. The latter evidence has produced enormous changes in law and societal practice, while racism in the death penalty has been largely ignored.

Despite overwhelming evidence of discrimination, the response of the courts has been to deny relief on the grounds that patterns of racial disparities are insufficient to prove racial bias in individual cases. With the single exception of Kentucky which recently passed a version of the Racial Justice Act, legislatures have turned their back on corrective measures. Despite the prior example of legislation in response to similar discrimination in such areas as employment and housing, legislatures on both the federal and state level have failed to pass civil rights laws regarding the death penalty for fear of stopping capital punishment entirely. And so, the sore festers even as executions accelerate and appeals are curtailed.

The human cost of this racial injustice is incalculable. The decisions about who lives and who dies are being made along racial lines by a nearly all white group of prosecutors. The death penalty presents a stark symbol of the effects of racial discrimination. In individual cases, this racism is reflected in ethnic slurs hurled at black defendants by the prosecution and even by the defense. It results in black jurors being systematically barred from service, and in the devoting of more resources to white victims of homicide at the expense of black victims. And it results in a death penalty in which blacks are frequently put to death for murdering whites, but whites are almost never executed for murdering blacks. Such a system of injustice is not merely unfair and unconstitutional – it tears at the very principles to which this country struggles to adhere.

It is tempting to pretend that minorities on death row share a fate in no way connected to our own, that our treatment of them sounds no echoes beyond the chambers in which they die. Such an illusion is ultimately corrosive, for the reverberations of injustice are not so easily confined.

The Sounds of Racism Top

Blatant racism is seen and heard too often in courtrooms around the country. In death penalty cases, the use of derogatory slurs kindles the flames of prejudice and allows the jury to judge harshly those they wish to scapegoat for the problem of crime. A few examples illustrate the intensity of this racism:

- “One of you two is gonna hang for this. Since you’re the nigger, you’re elected.“3 These words were spoken by a Texas police officer to Clarence Brandley, who was charged with the murder of a white high school girl. Brandley was later exonerated in 1990 after ten years on death row.

- In preparing for the penalty phase of an African-American defendant’s trial, a white judge in Florida said in open court: “Since the nigger mom and dad are here anyway, why don’t we go ahead and do the penalty phase today instead of having to subpoena them back at cost to the state.“4 Anthony Peek was sentenced to death and the sentence was upheld by the Florida Supreme Court in 1986 reviewing his claim of racial bias.

- A prosecutor in Alabama gave as his reason for striking several potential jurors the fact that they were affiliated with Alabama State University — a predominantly black institution. This pretext was considered race neutral by the reviewing court. 5

- During the 1997 election campaign for Philadelphia’s District Attorney, it was revealed that one of the candidates had produced, as an Assistant D.A., a training video for new prosecutors in which he instructed them about whom to exclude from the jury, noting that “young black women are very bad” on the jury for a prosecutor, and that “blacks from low-income areas are less likely to convict.“6 The training tape also instructed the new recruits on how to hide the racial motivation for their jury strikes.

- In Missouri, Judge Earl Blackwell issued a signed press release about his judicial election announcing his new affiliation with the Republican Party while presiding over a death penalty case against an unemployed African-American defendant. The press release stated, in part: “[T]he Democrat party places far too much emphasis on representing minorities … people who dont’ (sic) want to work, and people with a skin that’s any color but white .…“7 The judge denied a motion to recuse himself from the trial. The defendant, Brian Kinder, was convicted and sentenced to death, and Missouri’s Supreme Court affirmed in 1996.8

These examples are symbolic of a more systemic racism, and they provide a sense of how damaging racial prejudice and insensitivity can be when someone is facing execution. Empirical studies which provide the national evidence of racism in capital punishment are critical to understanding that this problem goes far beyond individual examples of prejudice.

The Raw Data Top

The first step in determining the presence of racial discrimination in the death penalty is to look at the raw data: from among the eligible homicides, how often are black defendants sentenced to death and how often are others sentenced to death?

The raw data of death sentences in Philadelphia between 1983 and 1993, provide the first piece of disturbing evidence that race discrimination may be operating. The rate at which eligible black defendants were sentenced to death was nearly 40% higher than the rate for other eligible defendants. A sentencing rate is simply a ratio of the number of death sentences for a particular group compared to the total number of cases of that group which would be eligible for a death sentence. In the chart below, a death sentencing rate of .18 for blacks means that for every 100 eligible black defendants, 18 will be sentenced to death. For other defendants, only 13 out of 100 will be similarly sentenced.

Taking Into Account the Severity of Murders Top

In order to determine whether race influences death sentencing, the researchers turned to the same techniques used in medical research to determine whether cigarette smoking causes cancer, or frequent exercise and good diet reduces heart attacks. Murder cases become death eligible through the existence of certain aggravating factors which make one murder “worse” than another. In deciding whether the death penalty should be sought, the prosecutor is supposed to consider the presence of such factors as whether a murder was committed with grave risk to the life of others, whether the murder was committed in the course of another serious crime such as robbery or rape, whether torture was used in the commission of the murder, or whether the defendant had a significant violent history. The jury is similarly told to consider such factors when deciding whether the sentence should be life or death, once a guilty verdict is rendered.12

Through an analysis of murders in which the death penalty could have been sought, it is possible, through an analysis of the defendants that were and were not sentenced to death, to assign a predictive score, or coefficient, to various aggravating factors to measure how heavily each influences the likelihood of a death sentence. The researchers screened hundreds of factors, statutory and non-statutory, to develop models to explain how the system works. All statutory factors, and those non-statutory factors which significantly correlated with the outcome were included.

Comparing the coefficients permits an average assessment of how much reliance was placed on the factor by the decision-makers. For example, the fact that the murder was committed in the course of another felony has less impact than the fact that the defendant caused great harm, fear or pain. Statistically, in this study committing another felony had a relative predictive value of 0.8. On the other hand, if the murder was accompanied by torture, that factor was very significant and registered a predictive value of 1.9. A murder committed with grave risk of death to others had a relatively high predictive value of 1.5. A factor which had no apparent effect would have a value of 0. The study looked at a large class of such variables.

The race of the defendant is not supposed to influence whether a person is sentenced to death, but in Philadelphia it clearly does. (See Chart below.) Murders by blacks are treated as more severe and “deserving” of the death penalty because of the defendant’s race. Being a black defendant merits a score of 1.4 in predicting whether a death sentence will ultimately result. This extra burden for black defendants is comparable to such legitimate aggravating factors as torture or “causing great harm, fear or pain,” which earned scores of 1.9 and 1.0 respectively, in predicting the sentence. Stated differently, in Philadelphia, the capital sentencing statute has operated as though being black was not merely a physical attribute, but as if it were one of the most important aggravating factors actually justifying the death penalty.

The race of the defendant is a much stronger predictor that a case will result in a death sentence than the fact that the crime was committed along with another felony (0.8) or that the defendant killed with multiple stab wounds (0.9). Either when the prosecutor decides to seek the death penalty in a particular case, or when the jury decides that death is the appropriate sentence, on average, black defendants are considered “worse,” regardless of the other factors in their case.

Mid-Range Cases Versus Extreme Cases Top

Race does not affect all cases equally. Notorious serial killers like Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy, both white, are nearly certain to receive the death penalty regardless of their race. In the most highly aggravated cases, the fact that the defendant is black is less of a factor pushing a case toward a death sentence. The same can be said for cases of very low severity: race is less likely to be a factor in cases where there is little inflammatory evidence.

But in the “mid-range” of severity (or aggravation), race plays a very significant role. When cases were ranked from 1 to 8 in increasing severity, cases in categories 1 (least severe) and 8 (most severe) showed little or no discrimination against black defendants. But in the middle categories 3 through 7, the disproportionate treatment of black defendants, as compared to all other defendants, was quite pronounced. For example, in cases of level 5 severity, 25% of the black defendants received the death penalty, but only 5% of the other defendants received death, and the difference between these sentencing rates is 20 percentage points. At level 6 severity, the difference was 15 percentage points, and at level 4 severity, the difference in death sentencing rates was 11 percentage points higher for black defendants. These results are summarized in the graph below.

In other areas of society, such as employment or housing, racial disparities similar to those shown in this death penalty study have raised deep concerns and have prompted civil rights legislation to protect the rights of minorities.13 But with the death penalty, this clear evidence of racial bias has gone uncorrected.

Black Defendants and the Race of the Victims Top

Another measure of race’s impact on the death penalty is the combined effect of the race of the defendant and the race of the victim. In the Philadelphia study, the racial combination which was most likely to result in a death sentence was a black defendant with a nonblack victim, regardless of how severe the murder committed. Black-on-black crimes were less likely to receive a death sentence, followed by crimes by other defendants, regardless of the race of their victims.

As noted above, in cases deemed to be least severe and those found to be most severe, the connection between race and the likelihood of a death sentence tends to lessen. For example, few defendants of any race are likely to get the death penalty in a case involving defendants with no prior record and where the killing may have been accidental. But for the bulk of crimes which are in the mid-level of severity, blacks who kill nonblacks are more likely to receive the death penalty than blacks who kill blacks, and they have a death sentencing rate much larger than the rate for defendants of other races who commit similarly severe murders of black victims.

It is important to note that these mid-range cases are precisely the ones in which prosecutors and jurors have the most discretion on seeking and imposing the death penalty. And when discretion is more prevalent, race may more easily become the deciding factor in who lives and who dies.

These results are summarized in the graph below. Reading the graph from left to right, black defendants, regardless of their victims’ race, are consistently more likely to receive a death sentence than other defendants, and this holds true to varying degrees throughout the increasing levels of crime severity. Similarly, black victim cases are less likely to receive the death penalty, regardless of the race of the defendant.

Philadelphia Study: Conclusions Top

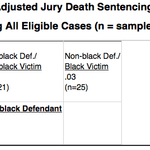

After controlling for levels of crime severity and the defendant’s criminal background, the average death sentencing rates in Philadelphia were .18 for black defendants and .13 for other defendants, which amounts to a 38% higher rate for blacks (coincidentally, these rates were approximately the same as the unadjusted rates on p.8). The disparities for various racial combinations of defendant and victim were even wider and are shown in the table below.

Whichever measures the researchers employed, the statistics pointed to the same conclusion: black defendants on average face a distinctly higher risk of receiving a death sentence than all other similarly situated defendants. The various independent tests were so thoroughly consistent that they pointed to race discrimination as the underlying cause. The researchers stated: “In the face of these results, we consider it implausible that the estimated disparities are a product of chance or reflect a failure to control for important omitted case characteristics.… In short, we believe it would be extremely unlikely to observe disparities of this magnitude and consistency if there were substantial equality in the treatment of defendants in this system.“14

For those on death row from Philadelphia, these numbers translate into a harsh and deadly reality: if the death penalty were applied to blacks as it is to others, there would be far fewer blacks facing execution.

National Patterns of Race Discrimination Top

When people of color are killed in the inner city, when homeless people are killed, when the “nobodies” are killed, district attorneys do not seek to avenge their deaths. Black, Hispanic, or poor families who have a loved one murdered not only don’t expect the district attorney’s office to pursue the death penalty – which, of course, is both costly and time consuming – but are surprised when the case is prosecuted at all. -Sister Helen Prejean, CSJ15

If the racial disparities documented in the study of capital cases in Philadelphia were unique, they might be dismissed as simply a local problem requiring a local solution. But such racial patterns have appeared in study after study all over the country and over an extensive period of time.

In the late 1980s, Congress asked the General Accounting Office (GAO) to review the empirical studies on race and the death penalty which had been conducted up to that time. The agency reviewed 28 studies regarding both race of defendant and race of victim discrimination. Their review included studies utilizing various methodologies and degrees of statistical sophistication and examined such diverse states as California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Texas. Their conclusion in 1990, based on the vast amount of data collected, was unequivocal:

In 82% of the studies, race of victim was found to influence the likelihood of being charged with capital murder or receiving a death sentence, i.e., those who murdered whites were found to be more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered blacks. This finding was remarkably consistent across data sets, states, data collection methods, and analytic techniques. The finding held for high, medium, and low quality studies.16

One of the most sophisticated of the studies reviewed by the GAO was the study of race and the death penalty in Georgia. This study looked at 2400 cases processed in Georgia over a seven year period. It showed that, even when controlling for the many variables which might make one case worse than another, defendants whose victims were white, faced, on average, odds of receiving a death sentence that were 4.3 times higher than similarly situated defendants whose victims were black.17 The study controlled for hundreds of variables such as the level of violence in the crime and the prior criminal record of the defendant.

The significance of this racial disparity is highlighted by comparing it to a smoker’s increased odds of dying from coronary artery disease. A pivotal study found their odds of dying were approximately 1.7 times higher than for non-smokers of similar ages,18 a factor smaller than that linking race and the death penalty. Such statistical evidence about the dangers of smoking led the Surgeon General to conclude that “cigarette smoking is a cause of coronary heart disease,“19 which, in turn, helped trigger legislation and significant reform. Yet the correlation between race and the death penalty is much stronger and has been met with virtual silence.

The study of racial disparities in Georgia was the basis for the most important case brought before the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of race and the death penalty, McCleskey v. Kemp (1987).20 The research was conducted by David Baldus, Professor of Law at the University of Iowa College of Law, and George Woodworth, Professor of Statistics also at the University of Iowa, both of whom participated in the Philadelphia study discussed above. For their work in what has become known as “the Baldus study,” these researchers were awarded the Harry Kalven Prize for distinguished scholarship by the Law and Society Association.

In a recent report prepared for the American Bar Association, Professors Baldus and Woodworth have expanded on the GAO’s review of studies on race discrimination in capital cases.21 They found that there are some relevant data in three-quarters of the states with prisoners on death row. In 93% of those states, there is evidence of race-of-victim disparities, i.e., the white race of the person murdered correlated with whether a death sentence will be given in a particular case. In nearly half of those states, the race of the defendant also served as a predictor of who received a death sentence. The disparities in nine states (CA, CO, GA, KY, MS, NJ, NC, PA and SC) are particularly notable because of their reliance on well-controlled studies.

These disparities reveal a disturbing and consistent trend indicating race-of-victim discrimination. For example, in Florida, a defendant’s odds of receiving a death sentence are 4.8 times higher if the victim was white than if the victim is black in similarly aggravated cases. In Illinois, the multiplier is 4, in Oklahoma it is 4.3, in North Carolina 4.4, and in Mississippi it is 5.5.22 The table below shows how frequently race-of-victim discrimination has been detected, as well as the states where race-of-defendant disparities have been shown.

Figure 7: Statistical Data in Death Penalty States Showing a Risk of Racial Discrimination 23 Top

Only studies whose results were statistically significant, or where the ratio between death sentencing (or prosecutorial charging) rates (e.g., between white victim and black victim cases) was 1.5 or larger and with a sample size of at least 10 cases in each group, were included. The disparities in nine states (CA, CO, GA, KY, MS, NJ, NC, PA and SC) are based on well-controlled studies. The results in the other states are from less well-controlled studies and are only suggestive.

All of the race of victim disparities except one (Delaware) were in the direction of more death sentences in white victim cases.

All of the race of defendant disparities except two (Florida and Tennessee) were in the direction of more death sentences for black defendants.

A particularly egregious example of race of victim discrimination was revealed in a recent review of the cases from Kentucky’s death row. Researchers at the University of Louisville had found in 1995 that, as in other states, blacks who killed whites were more likely to receive the death penalty than any other offender-victim combination.24 In fact, looking at the makeup of Kentucky’s death row in 1996 revealed that 100% of the inmates were there for murdering a white victim, and none were there for the murder of a black victim, despite the fact that there have been over 1,000 African-Americans murdered in Kentucky since the death penalty was reinstated.25This gross disparity among capital cases sends a message that the taking of a white life is more serious than the taking of a black life, and that Kentucky’s courts hand out death sentences on that basis.

This biased use of the death penalty for the murder of those in the white community, but not those in the black community, led to the introduction of legislation allowing consideration of such patterns of racial disparities. The bill, referred to as the “Racial Justice Act,” failed in the Kentucky legislature in 1996,26 but was passed in 1998. It will permit race-based challenges to prosecutorial decisions to seek a death sentence.

No Relief in the Courts Top

Despite these pervasive patterns implying racial discrimination, courts have been closed to challenges raising this issue. In McCleskey v. Kemp, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the defendant had to show that he was personally discriminated against in the course of the prosecution. “Merely” showing a disturbing pattern of racial disparities in Georgia over a long period of time was not sufficient to prove bias in his case.27

The federal courts have taken their cue from McCleskey and have not granted relief based on a racial application of the death penalty in any case.28 When such claims of racial bias are raised in civil rights suits alleging employment or housing discrimination, civil rights legislation instructs the courts to employ a more commonsensical burden of proof and provides a chance for relief.29 In criminal cases, however, the courts require the defense to “get inside” the mind of the prosecutor or jury and show purposeful race discrimination directed at the defendant, an almost impossible task.

Study II: The Race of the Decision-Makers Top

The death penalty is essentially an arbitrary punishment. There are no objective rules or guidelines for when a prosecutor should seek the death penalty, when a jury should recommend it, and when a judge should give it. This lack of objective, measurable standards ensures that the application of the death penalty will be discriminatory against racial, gender, and ethnic groups. -Rev. Jesse Jackson (1996)30

As the analysis above indicates, racially biased decisions can readily enter the criminal justice system through the discretion given to prosecutors to selectively seek the death penalty in some cases but not others. The GAO review of race discrimination noted that “race of victim influence was found at all stages of the criminal justice process” and that “[t]he evidence for the race of victim influence was stronger for the earlier stages of the judicial process (e.g., prosecutorial decision to charge the defendant with a capital offense, decision to proceed to trial rather than plea bargain) than in later stages.“31

The death penalty could be sought in far more cases than it actually is, and prosecutors use a variety of factors to determine which cases are deserving of the state’s worst punishment. That discretion more likely results in capital prosecutions when the victim in the underlying murder is white, and in some states, when the defendant is black. Except for extreme cases, as when a black police officer is killed, the murder of people of color is not treated as seriously as the murder of white people.

One of the likely reasons for this discrepancy is that almost all the prosecutors making the key decision about whether death will be sought are white. According to a new study soon to be published in the Cornell Law Review, only 1 percent of the District Attorneys in death penalty states are black. This staggering imbalance in the racial makeup of the life and death decision-makers may partially explain the persistent racial imbalance in the use of the death penalty.

Professor Jeffrey Pokorak of St. Mary’s University School of Law collected data regarding the race and gender of the government officials empowered to prosecute criminal offenses, and in particular, capital offenses from all 38 states that use the death penalty. The study was concluded in February, 1998.

It revealed that only 1% of the District Attorneys in death penalty states in this country are black and only 1% are Hispanic. The remaining 97.5% are white, and almost all of them are male. The chart below Fig. 9) summarizes the racial findings of Professor Pokorak’s study.

The implications of this study go far beyond the shocking numbers and racial isolation of those in this key law enforcement position. When a prosecutor is faced with a crime in his community, he often consults with the family of the victim as to whether the death penalty should be sought. If the victim’s family is prominent, white, and likely to support him in his next election, there may be a greater willingness to expend the extensive financial resources and time which a death penalty prosecution will take. Justice Harry A. Blackmun

The way that racial bias can play out in practice is illustrated by one of the key death penalty jurisdictions in the country: Georgia’s Chattahoochee Judicial District, which has sent more people to death row than any other district in the state. In a recent law review article, Stephen Bright, of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, described the prosecutor’s practice there:

- [A]n investigation of all murder cases prosecuted … from 1973 to 1990 revealed that in cases involving the murder of a white person, prosecutors often met with the victim’s family and discussed whether to seek the death penalty. In a case involving the murder of the daughter of a prominent white contractor, the prosecutor contacted the contractor and asked him if he wanted to seek the death penalty. When the contractor replied in the affirmative, the prosecutor said that was all he needed to know. He obtained the death penalty at trial. He was rewarded with a contribution of $5,000 from the contractor when he successfully ran for judge in the next election. The contribution was the largest received by the District Attorney. There were other cases in which the District Attorney issued press releases announcing that he was seeking the death penalty after meeting with the family of a white victim. But prosecutors failed to meet with African-Americans whose family members had been murdered to determine what sentence they wanted. Most were not even notified that the case had been resolved. As a result of these practices, although African-Americans were the victims of 65% of the homicides in the Chattahoochee Judicial District, 85% of the capital cases were white victim cases.33

Racial Bias Permeates the System Top

Even under the most sophisticated death penalty statutes, race continues to play a major role in determining who shall live and who shall die. -Justice Harry Blackmun, 1994 34

Prosecutors not only decide who should be charged with a particular level of offense, they also have a significant impact on the way the trial is conducted. When a prosecutor refers to an Hispanic defendant as “a chili-eating bastard,“35 as happened in a Colorado death penalty case, it sets a tone of acceptance of racial prejudice for the entire trial. Similarly, the selection of juries is an essential part of this process, and some prosecutors have made a practice of eliminating blacks from their prospective juries, thereby increasing the likelihood of a race-based decision.

Jack McMahon, for example, was an Assistant District Attorney for many years in Philadelphia. During his recent campaign for the District Attorney’s position, it was revealed that he carefully instructed new prosecutors in his office on the importance of keeping many blacks off high level criminal cases. His training video for prosecutors stated that “young black women are very bad” on the jury for a prosecutor, and that “blacks from low-income areas are less likely to convict.“36

If a new prosecutor did not follow his directives, he or she faced dismissal: “And if you go in there and any one of you think you’re going to be some noble civil libertarian and try to get jurors [who say they’ll be fair], that’s ridiculous. You’ll lose and you’ll be out of the office; .…“37

His tape urged his fellow prosecutors to pick juries that they knew would be unfair: “[T]he only way you’re going to do your best is to get jurors that are as unfair and more likely to convict than anybody else in that room.“38

Mr. McMahon, himself, prosecuted 36 murder cases and some of those defendants are presently on death row in Pennsylvania. In selecting juries, McMahon practiced what he preached. In a review of 16 first-degree murder cases prosecuted by McMahon, black jurors were struck four times as often as other jurors, and black women jurors were struck six times as often as non-African-American males.39

But McMahon was certainly not alone in this practice of racial discrimination in jury selection. Statistics from the race study in Philadelphia discussed above showed that from 1983 to 1993 prosecutors struck 52% of all black potential jurors, but only 23% of other potential jurors.

These same practices are common in other jurisdictions. According to a recent federal court decision in Alabama reviewing a death penalty case, the Tuscaloosa District Attorney’s Office had a “standard operating procedure … to use the peremptory challenges to strike as many blacks as possible from the venires in cases involving serious crimes.” 40

In the Chattahoochee Judicial District of Georgia, described above, prosecutors used 83% of their peremptory jury strikes against African-Americans. Six black defendants were tried by all-white juries.41

In the Ocmulgee Judicial District of Georgia, District Attorney Joseph Briley tried 33 capital cases between 1974 and 1994. Twenty-four were against black defendants. In cases in which the defendant was black and the victim was white, Briley used 96 out of his 103 jury challenges against African-Americans.42

In Chambers County, Alabama, the prosecutor kept lists dividing prospective jurors into four categories: “strong,” “medium,” “weak,” and “black.” Such a process led to striking 26 African-American jurors, resulting in three all-white juries in the death penalty prosecution of Albert Jefferson, a black defendant whose victim was white. An Alabama court found that no racial discrimination had occurred.43

The U.S. Supreme Court in Batson v. Kentucky ruled that it is unconstitutional to strike jurors solely on the basis of race. Prosecutors, however, sometimes circumvent this ruling by providing race-neutral reasons as a pretext for eliminating unwanted black jurors. In Philadelphia, Assistant D.A. Jack McMahon prepared his new prosecutors for just such manipulation in his training tape mentioned above:

- In the future, we’re going to have to be aware of [Batson], and the best way to avoid any problems with it is to protect yourself. And my advice would be in that situation is when you do have a black jury, you question them at length. An on this little sheet that you have, mark something down that you can articulate later if something happens .…

So if – let’s say you strike three blacks to start with, the first three people. And then it’s like the defense attorney makes an objection saying that you’re striking blacks. Well, you’re not going to be able to go back and say, oh– and make up something about why you did it. Write it down right then and there.… And question them [the black jurors], say, “Well, he had a –had a” — “Well the woman had a kid about the same age as the defendant and I thought she’d be sympathetic to him” or “She’s unemployed and I just don’t like unemployed people” .…

So sometimes under that line you may want to ask more questions of those people so it gives you more ammunition to make an articulable reason as to why you are striking them, not for race.45

In another jurisdiction, prosecutors followed McMahon’s strategy precisely. Their spurious reasons for excluding black jurors were exposed by the Florida Supreme Court in reviewing the death penalty conviction of Robert Roundtree. At trial, the judge simply accepted the state’s explanations at face value as the prosecutor eliminated ten black jurors from the jury pool. The first two black jurors were dismissed because they were “inappropriately dressed” and one had on “pointy New York shoes.” At the same time, a similarly dressed white juror was accepted. Another black juror was rejected because she was thirty years old and unemployed, but a white unemployed female was accepted. Three blacks were excused, in part, because they were single, but five white single jurors were accepted. And the reason given for striking another black woman was that the state preferred a predominantly male jury, although the state had accepted 13 white females, 6 of whom sat on the final jury. The reviewing court found that “the proffered reasons were a pretext for racial discrimination” and reversed the conviction.46

Prosecutors are not alone in acting out of racial prejudice. Judges, defense attorneys and jurors can also display harmful racial bias. It is the defendant, however, who suffers the consequences. In the death penalty trial of Ramon Mata in Texas, the prosecutor and the defense attorney agreed to excuse all prospective minority race jurors, thereby ensuring an all white jury. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found this to be harmless error.47

In the Georgia trial of Wilburn Dobbs, a black man charged with the murder of a white man, both the judge and his attorney referred to Dobbs as a “colored boy.” The defense attorney expressed his opinion that “blacks are uneducated and would not make good teachers, but do make good basketball players,” and referred to the black community in Chattanooga as “black boy jungle.“48 Dobbs was sentenced to death, and his conviction has been upheld by the Georgia courts.

In Utah, African-American William Andrews was executed despite the presence of a note found by a juror depicting a stick figure on a gallows with the inscription: “Hang the Nigger’s (sic).” Even after seeing this evidence of racial prejudice within the all-white jury, the trial judge never sought to determine who wrote the note or how many jurors saw it.49

William Henry Hance, a mentally impaired black man was sentenced to death in Georgia despite the fact that one of the jurors said she did not vote for death. The only black person on the jury stated that she had voted for a life sentence because of Hance’s mental condition, but her vote was ignored. In the courtroom, she was intimidated against speaking out, but she later revealed her vote and the strong racial overtones in the jury room. Another juror signed an affidavit confirming the black juror’s story, but Mr. Hance was executed anyhow in 1994.50

Public Reaction Top

By reserving the penalty of death for black defendants, or for the poor, or for those convicted of killing white persons, we perpetrate the ugly legacy of slavery– teaching our children that some lives are inherently less precious than others. -Rev. Joseph E. Lowery, former President, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1989 51

After the Civil War and the emancipation of the slaves, lynchings of black people were common in the U. S. From the late 1800s, at least 4,743 people were killed by lynch mobs, with 90% of the lynchings occurring in the South, and most of the victims being black people.52 Lynchings were praised as necessary and just, and even some governors deferred to the public demand for vengeance. Georgia populist Tom Watson observed that “Lynch law is a good sign; it shows that a sense of justice yet lives among the people.“53

Revulsion at the spectacle and gross injustices of the lynching era eventually led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and then to the demise of lynching.54 But the disparities evident in today’s death penalty indicate that prejudice and racism remain a potent force infecting our system of justice.

These racial disparities in capital punishment have drawn increasingly critical reaction from legal and civil rights groups both nationally and internationally. After the Supreme Court narrowly rejected a challenge to the racially biased application of the death penalty in Georgia,55 civil rights groups and many newspaper editorials called for the passage of the Racial Justice Act to remedy this injustice on a national level. Although this proposed legislation was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1994 and 1990, it was ultimately defeated on the theory that such a racial inquiry would “abolish” the death penalty. Only Kentucky has passed similar legislation on the state level.

As a result of this and other inequities in the administration of capital punishment, the ABA, which had earlier recommended the passage of the Racial Justice Act,56 has called for a complete moratorium on executions until such problems can be adequately addressed. Other bar associations such as the Pennsylvania Bar, the Ohio Bar, the Chicago Council of Lawyers, the Massachusetts Bar and the Philadelphia Bar have either endorsed the ABA’s resolution or passed similar resolutions. Over 100 other organizations have also endorsed motions to stop executions, at least until a greater sense of justice can be restored to the process.57

Evidence of racial discrimination in the U.S. death penalty system has attracted worldwide attention. In 1996, the International Commission of Jurists, whose members include respected judges from around the world, visited the United States and researched the use of the death penalty. Their report was sharply critical of the way the death penalty is being applied, particularly in regards to race: “The Mission is of the opinion that … the administration of capital punishment in the United States continues to be discriminatory and unjust — and hence ‘arbitrary’ –, and thus not in consonance with Articles 6 and 14 of the Political Covenant and Article 2(c) of the Race Convention.“58

In a March, 1998 decision,59 the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights concluded that the U.S. had violated international law and should compensate the relatives of William Andrews, who was executed in Utah in 1992, because of racial bias in his case (discussed above).

And most recently, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions filed a report with the U.N. Commission on Human Rights after his visit to the U.S. stating that “race, ethnic origin and economic status appear to be key determinants of who will, and will not, receive a sentence of death.“60

In Philadelphia, the Secretary General of Amnesty International criticized Pennsylvania’s death penalty as “one of the most racist and unfair in the U.S.“61 Hours after his speech, the Philadelphia Bar voted in favor of a resolution calling for a moratorium on the death penalty in that state. The Governor’s office responded by pointing out that the only two persons executed in Pennsylvania in recent times were both white. However, these men were the exception, having been executed before others only because they waived their appeals. The overwhelming majority of those on the state’s death row are black, and 84% of those on death row from Philadelphia are black.62

Religious opposition to the death penalty has also cited the racial unfairness in its application. Recently, all the Catholic Bishops in Texas signed a statement calling for an end to the death penalty, noting: “The imposition of the death penalty has resulted in racial bias. In fact, the race of the victim has proven to be the determining factor in deciding whether to prosecute capital cases.“63 Similar concerns have been voiced by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops and the leaders of other denominations.

The public in this country is very aware of the role race plays in the death penalty. A recent poll by Newsweek Magazine revealed that about half of all Americans believe that a black person is more likely to receive the death penalty than a white person for the same crime.65 When such public reaction will result in a challenge to this injustice is not clear. Until then, it remains a serious source of division among the races and an embarrassment to the U.S.‘s pursuit of international human rights.

Conclusion Top

Those whom we would banish from society or from the human community itself often speak in too faint a voice to be heard above society’s demand for punishment. It is the particular role of courts to hear these voices, for the Constitution declares that the majoritarian chorus may not alone dictate the conditions of social life. -Justice William Brennan, 198766

The influence of race on the death penalty is pervasive and corrosive. In other areas of the law, protections have been built in to limit the effects of systemic racism when the evidence of its impact is clear. With the death penalty, however, such corrective measures have been blocked by those who claim that capital punishment would bog down if racial fairness was required. And so, the sore festers.

The new studies revealed through this report add to an overwhelming body of evidence that race plays a decisive role in the question of who lives and dies by execution in this country. Race influences which cases are chosen for capital prosecution and which prosecutors are allowed to make those decisions. Likewise, race affects the makeup of the juries which determine the sentence. Racial effects have been shown not just in isolated instances, but in virtually every state for which disparities have been estimated and over an extensive period of time.

Those who die because of this racism are not the kind of people who usually evoke the public’s sympathy. Many have committed horrendous crimes. But crimes no less horrendous are committed by white offenders or against black victims, and yet the killers in those cases are generally spared death. The death penalty today is a system which vents society’s anger over the problem of crime on a select few. The existing data clearly suggest that many of the death sentences are a product of racial discrimination. There is no way to maintain our avowed adherence to equal justice under the law, while ignoring such racial injustice in the state’s taking of life.

Appendix Top

Note: All photographs are printed with permission. The photographs of Justices Marshall and Blackmun are by Joseph Lavenburg (Natl. Geographic Soc.), and the photograph of Justice Brennan is by Ken Heinen, all from the Collection, The Supreme Court of the United States, courtesy The Supreme Court Historical Society. The other photographs were received with permission from their subjects.

1. J. Pokorak, Probing the Capital Prosecutor’s Perspective: Race and Gender of the Discretionary Actors, xx Cornell Law Review xxx (1998) (forthcoming).

2. McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 344 (1987) (Brennan, J., dissenting).

3. N. Davies, White Lies: Rape, Murder, and Justice Texas Style 23 (1991) (quoting testimony in the appeal of Clarence Brandley).

4. Peek v. Florida, 488 So.2d 52, 56 (Fla. 1986).

5. See B. Stevenson & R. Friedman, Deliberate Indifference: Judicial Tolerance of Racial Bias in Criminal Justice, 51 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 509, 522 (1994).

6. See M. Janofsky, Under Siege, Philadelphia’s Criminal Justice System Suffers Another Blow, New York Times, April 10, 1997.

7. See Appellant’s Brief, Missouri v. Kinder, No. 75082 (Missouri Supreme Court, 1996) for complete text of press release (on file with the Death Penalty Information Center).

8. See State v. Kinder, 942 S.W.2d 313 (Mo. 1996).

9. Speech at Annual Dinner in Honor of the Judiciary, American Bar Association, 1990, quoted in The National Law Journal, Feb. 8, 1993.

10. T. Rosenberg, The Deadliest D.A., N.Y. Times Magazine, July 16, 1995, at 22.

11. This study was conducted by David Baldus, George Woodworth and others in 1996 – 98. Statistical data is available in part from the Death Penalty Information Center. The preliminary Philadelphia results reported herein will be published in the Cornell Law Review in the Fall of 1998.

12. In Pennsylvania, the jury can arrive at a death sentence in two ways: a) it finds at least one aggravating factor, but no mitigating factors, which then requires a mandatory death sentence; or b) it finds at least one aggravating factor and one mitigating factor, which then must be weighed to determine the proper sentence. Pa. Stat. Ann. tit. 42, § 9711(c)(1)(iv) (Purdon 1982).

13. See Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e to e‑17 (1988) (equal employment opportunities); 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 – 3619 (1988) (fair housing).

14. D. Baldus, et al., Race Discrimination and the Death Penalty in the Post Furman Era: An Empirical and Legal Overview, with Preliminary Findings from Philadelphia, xx Cornell Law Review xxx (1998) (forthcoming).

15. H. Prejean, Would Jesus Pull the Switch?, Salt of the Earth, March/April, 1997, at 12.

16. U.S. General Accounting Office, Death Penalty Sentencing: Research Indicates Pattern of Racial Disparities (1990), at 5 (emphasis added) (hereafter GAO Report).

17. See D. Baldus, et al., Reflections on the “Inevitability” of Racial Discrimination in Capital Sentencing and the “Impossibility” of Its Prevention, Detection, and Correction, 51 Washington & Lee Law Review 359, 365 (1994).

18. See S. Gross & R. Mauro, Death & Discrimination: Racial Disparities in Capital Sentencing 151 (1989).

19. Id. at 172, citing U.S. Dept. of Health, Education & Welfare, Smoking and Health, A Report of the Surgeon General, at 60 (1979).

20. 481 U.S. 279 (1987).

21. D. Baldus & G. Woodworth, Race Discrimination in America’s Capital Punishment System Since Furman v. Georgia (1972): The Evidence of Race Disparities and the Record of Our Courts and Legislatures in Addressing This Issue (1997) (report prepared for the American Bar Association) (hereinafter ABA Report).

22. See Gross & Mauro, Patterns of Death: An Analysis of Racial Disparities in Capital Sentencing and Homicide Victimization, 37 Stanford L. Rev. 27, 78, 96 (1984); S. Gross & R. Mauro, Death and Discrimination: Racial Disparities in Capital Sentencing 65 – 66 (1989).

23. The statistical bases of many of these disparities can be found at D. Baldus, et al., Arbitrariness and Discrimination in the Administration of the Death Penalty: A Challenge to State Supreme Courts, 15 Stetson Law Review 133, 159 – 60, 163 – 64 (1986), and in the works of Gross & Mauro, note 22 above; see also ABA Report, note 21 above, at Appendix A, for a citation for each state study.

24. T. Keil & G. Vito, Race and the Death Penalty in Kentucky Murder Trials: 1976 – 1991, 20 American Journal of Criminal Justice 17 (1995).

25. See Editorial, Who Gets to Death Row, Kentucky Courier-Journal, Mar. 7, 1996 (citing Univ. of Louisville study).

26. See M. Chellgren, Race-bias Bill Rejected, Could Get New Hearing, The Kentucky Enquirer, Mar. 26, 1996.

27. See McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 292 (1987).

28. See J. Acker, et al., editors, America’s Experiment with Capital Punishment: Reflections on the Past, Present, and Future of the Ultimate Penal Sanction 409 (1998) (article on race discrimination by D. Baldus & G. Woodworth).

29. See Title VII of Civil Rights Act of 1964, note 13 above.

30. J. Jackson, Legal Lynching: Racism, Injustice and the Death Penalty 97 (1996).

31. GAO Report, note 16 above, at 5.

32. See Pokorak, note 1 above.

33. S. Bright, Discrimination, Death and Denial: The Tolerance of Racial Discrimination in Infliction of the Death Penalty, 35 Santa Clara Law Review 433, 453 – 54 (1995) (emphasis added).

34. Callins v. Collins, 114 S. Ct. 1127, 1135 (1994) (Blackmun, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari).

35. See People v. Sharpe, 781 P.2d 659, 660 (Colo. 1989) (censuring the prosecutor).

36. See Janofsky, note 6 above.

37. DATV Productions, Jury Selection With Jack McMahon, transcript at 45 – 46 (1987) (hereinafter McMahon Tape).

38. Id. at 46.

39. Petitioner’s Brief, Commonwealth v. Wilson, Nos. 3267, 3270 & 3271 (Pa. Ct. of Com. Pleas, Phil. Oct., 1997), Supplement to Petition for Post-Conviction Relief Under Article I, Sec. 14 and Post-Conviction Relief Act, ¶¶ 3 & 4.

40. Jackson v. Thigpen, 752 F. Supp. 1551, 1554 (N.D. Ala. 1990), rev’d in part and aff’d in part, sub nom. Jackson v. Herring, 42 F.3d 1350 (11th Cir. 1995).

41. See Bright, note 33 above, at 456.

42. Id. at 457.

43. Id. at 448.

44. 476 U.S. 79 (1986).

45. McMahon Tape, note 37 above, at 69 – 71 (emphasis added).

46. See Roundtree v. State, 546 So.2d 1042 (Fla. 1989).

47. Mata v. Johnson, 99 F.3d 1261 (5th Cir. 1996).

48. Dobbs v. Zant, 720 F. Supp. 1566, 1577 (N.D. Ga. 1989), aff’d, 963 F.2d 1403 (11th Cir. 1991), rev’d, 113 S. Ct. 835 (1993).

49. See J. Yang, A Rallying Point for Blacks in Utah, Washington Post, Feb. 26, 1992, at A4‑5.

50. See Georgia Rejects Clemency for a Killer Who Says He’s Retarded, N.Y. Times, Mar. 31, 1994, at A19.

51. Testimony of Rev. Dr. Joseph E. Lowery, President, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Oct. 2, 1989, at 3.

52. See S. Bright, note 33 above, at 440.

53. R. Johnson, Death Work: A Study of the Modern Execution Process 33 (1998).

54. See, e.g., J. Marquart, et al., The Rope, the Chair, and the Needle: Capital Punishment in Texas, 1923 – 1990 8 – 13 (1994).

55. McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987).

56. American Bar Association, Policy and Procedures Handbook (1988).

57. A list of endorsing organizations is available from Equal Justice, a project of the Quixote Center, Hyattsville, MD.

58. International Commission of Jurists, Administration of the Death Penalty in the United States (June, 1996), at 68 (Findings of The Mission, vi).

59. Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Report No. 57/96 (1998).

60. E. Olson, U.N. Report Criticizes U.S. for ‘Racist’ Use of Death Penalty, N.Y. Times, April 7, 1998, at A17.

61. M. Matza, Activist Blasts Pa. Over Death Penalty, Philadelphia Inquirer, Nov. 26, 1997.

62. Id.

63. Statement by Catholic Bishops of Texas on Capital Punishment, Oct. 20, 1997.

64. See, e.g., R. Marquand, Death-Penalty Issue Stirs Divergent Religious Views, The Christian Science Monitor, June 12, 1997 (“Conventional religious opposition to the death penalty includes points familiar to secular opponents. They include … the disproportionate rate of execution of poor and minority inmates;”).

65. See T. Morgenthau & P. Annin, Should McVeigh Die?, June 16, 1997, at 27 (“49% of all those polled say a black is more likely than a white to receive the death penalty for the same crime”).

66. McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 343 (1987) (Brennan, J., dissenting).